Jo Ractliffe has for decades been photographing the charged and ravaged landscapes of her native South Africa. For nearly as long, she has bristled at the insufficiency of the art-historical term “landscape” in encapsulating her interest in terrains where histories of occupation, use, conflict, and violence do not obviously declare themselves. Sometimes, and only partly in jest, she has used the term “blandscape” to characterize her abstruse images of nothing much in particular, be it a locked gate to an Apartheid-era torture site or desert landscape linked to a forgotten Cold War battleground. Last year, when Ractliffe was shortlisted for the 2022 Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, she repeated this dislike, describing landscape as a “difficult term,” more descriptive of an outlook or prospect than a space or place. “I think of [landscape] less as a ‘subject’, or genre,” she adds, “than the medium through which I can explore questions of violence, conflict, and memory.”1

Ractliffe’s new exhibition “Landscaping,” her first major statement since her 2020 survey exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, extends her interest in land as tangible fact and immanent subject. It is a remarkable career statement. Her thirty-four black-and-white photos, the majority taken over the past two years during long-distance drives from her home in Cape Town to places along the arid western coast of South Africa, record evidence of human occupation, initiative, and death. Her way of looking—curiously, critically, spatially, architecturally—has been honed over many years. The exhibition acknowledges this with the inclusion of five works from an earlier trip, in 2010, to the Atlantic Ocean settlement of Equinima in southern Angola.

The series “Equinima I–V” (2010) variously shows fragile and mummified human shelters, all of them made from irregular wooden stakes and industrial fabrics, each seen from a different angle and proximity. Equinima V also evidences the only sign of animal life in an otherwise unpeopled exhibition, a seagull coasting above an emergent refuge—the whale shown in Lambert’s Bay (2023) is a sculpture. But for the enigma of an unzipped suitcase photographed like a split tropical fruit on a burnt-out patch of earth at Saldanha Bay, surrounded by animal bones and empty liquor bottles, Ractliffe is not visibly drawn to the spectacular. In the main her subjects are mounds, piles, embankments, enclosures, and fragile encampments.

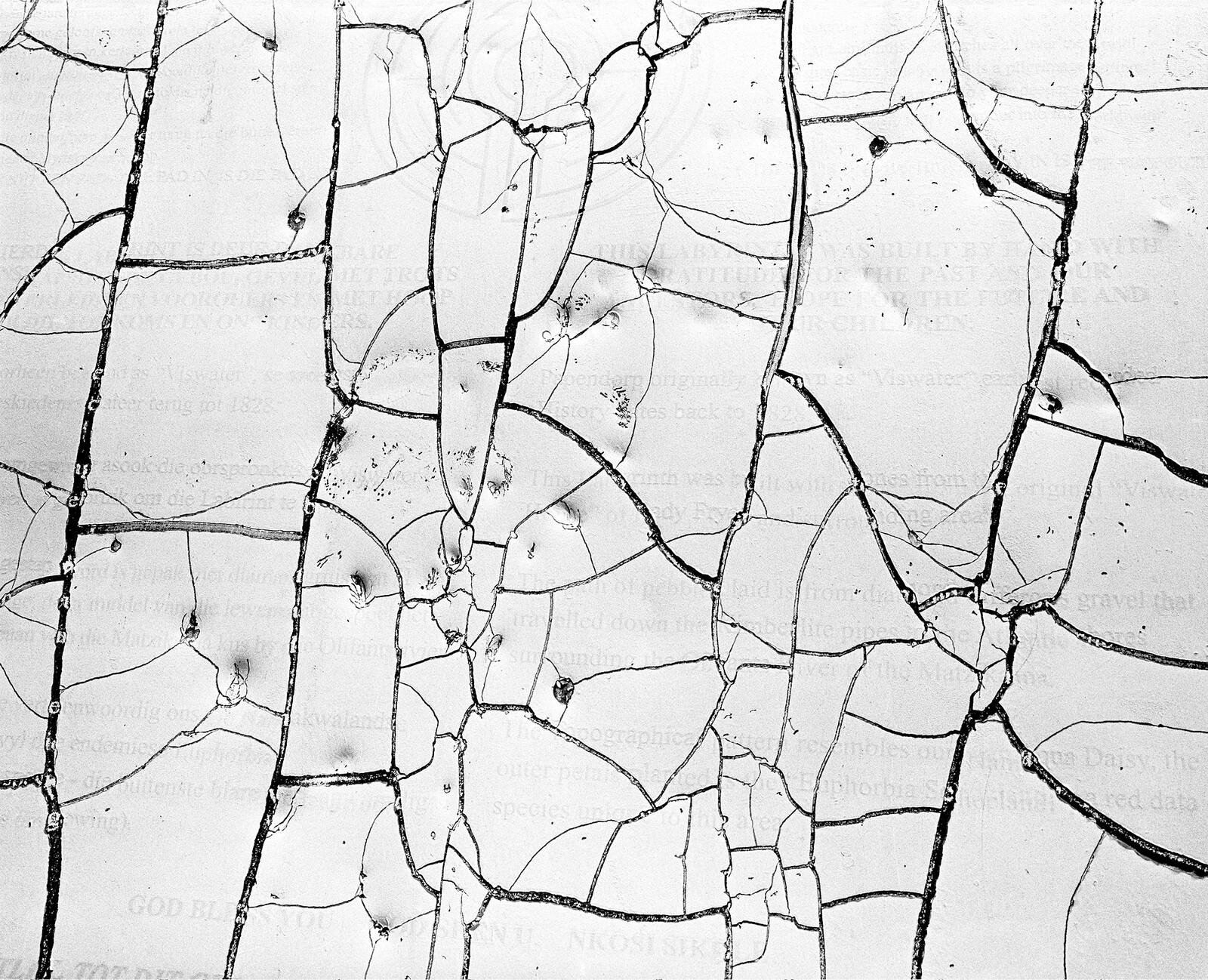

Upon entering the exhibition, the first three works show, from left to right, a mound of dry kelp sighted in Hondeklipbaai, an embankment of quarried granite seen in Aggeneys (it is a triptych composed of three different orientations, from close up to a receding view), and a weathered sign in Papendorp referring to an out-of-shot labyrinth built with stones dredged up during aquatic diamond mining. “This labyrinth was built by hand,” reads a feint snatch of words, which seems fitting in relation to this exhibition of frequently gorgeous but also unyielding images named after some of the remotest parts of South Africa.

Many of the places portrayed are sites of industrial activity and mining, like the salt works at Velddrif, granite quarry in Nababeep, and brickworks in Georgedale. The names of these and other places reveal the dispersed extent of South Africa’s nineteenth-century mineral revolution, which brutalized the land and left a polyglot imprint on it as well. Port Nolloth, where Ractliffe made a droll photo of a cemetery with a small sign reading “sold” on an empty plot, was once called Robbe Bay before it was renamed for the Royal Navy commander who surveyed the bay in 1854. The old Afrikaans name was itself an imposition, the indigenous Khoisan knowing the area as Aukotowa, or “place where the men perish.” Similarly, Okiep, where Ractliffe photographed a brick chimney jutting from between the folds of a rock-strewn landscape, derives its name from the Nama word for “a large brackish place.”

The bland and unlovely subject matter of many of Ractliffe’s photographs recall her friend and mentor David Goldblatt’s well-known expression, used in relation to his own work: “fuck-all landscapes.”2 As was the case with Goldblatt, literary figures have had an outsize influence on Ractliffe’s work. Where her earlier projects referenced the literary output of Russell Hoban and Ryszard Kapuściński—also the blue-collar lyricism of Nebraska-era Bruce Springsteen (“Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact”)—the new photographs draw on writings in a different register. Ractliffe variously references cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove, art historian W.J.T. Mitchell, environmental humanities scholar Rob Nixon, and artist William Kentridge in her artist statement.

In a 1988 essay, Kentridge railed against “the plague of the picturesque” that had infected South African art, especially painting. He described the unpeopled prospects of unsullied nature by white modernist painters as “documents of disremembering”.3 Ractliffe wants to invite historical memory into her photographs, albeit indirectly. Her new body of work is about the longue durée of South Africa’s mineral revolution, its aftermath as much as its endurance. It is a palpable but imprecise subject to figure, because it is about what Nixon refers to as slow violence: “a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.”4 It is this unspooling event, which is arguably beyond the temporal capabilities of photography, that is the ambitious subject of Ractliffe’s gripping new work.

“DBPFP22: Jo Ractliffe,” The Photographers’ Gallery (2022), https://thephotographersgallery.org.uk/dbpfp22-jo-ractliffe.

This much-quoted expression has an imprecise provenance but is usefully summarized by Leora Maltz-Leca in William Kentridge: Process as Metaphor and Other Doubtful Enterprises (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018), 73.

William Kentridge, “Landscape in a State of Siege,” Stet, vol. 5, no. 3 (November 1988): 15–18.

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 2.