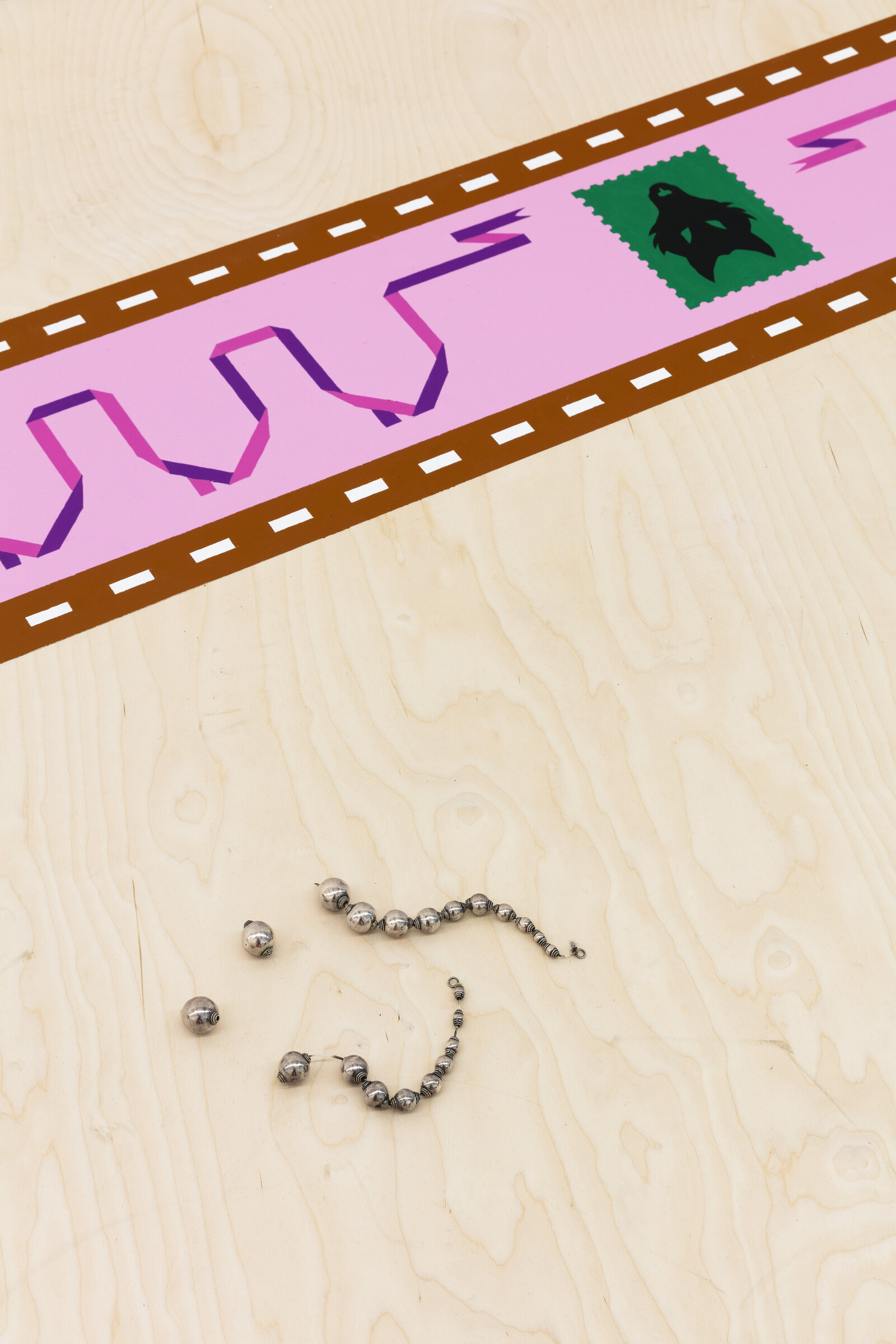

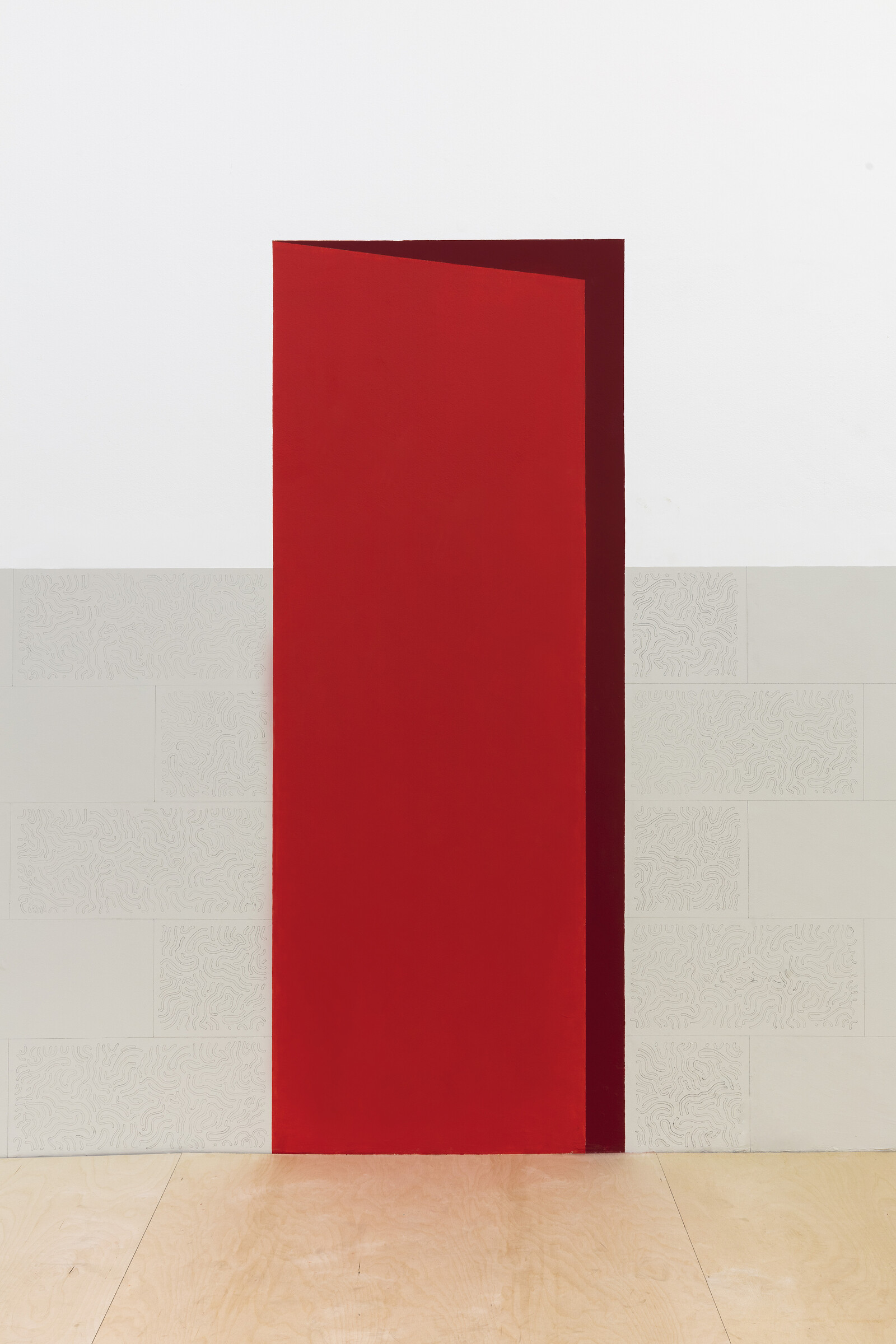

Kasper Bosmans has turned the Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro outside in. On entering his solo exhibition, the visitor is presented with a reproduction of a stylized city: painted onto the walls in shades of red are two ajar doors; assorted memorabilia can be glimpsed through a window display; a mural resembles a fake stone wall; and a thin pink highway painted on the floor, beside which rests an object resembling a discarded necklace, directs the viewer to a red wall on which hang three paintings the size of standard letter paper. Curator Eva Fabbris approached Bosmans about a show before the pandemic. The project morphed over the following months to suit the radically changing conditions, and to reflect art institutions’ ongoing anxiety over how they relate to their audiences. “A Perfect Shop-Front” could be thought of as a kind of trompe l’oeil: the minimal rendering of an urban project within an institution. A tiny strip of the city has percolated into an exhibition space, creating a zone of thresholds in which the boundaries between inside and outside are thin.

A serendipitous detail: Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro is located just a few steps from Milan’s Navigli, two artificial water channels built in the Middle Ages. The canals are surrounded by the eponymous, formerly working-class district, which from the 1970s onwards was populated by students and intellectuals and, more recently, became a gentrified area filled with cocktail bars and restaurants—as illustrated in Umberto Eco’s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum, in which a fictional local bistro is the meeting point for the city’s extravagant publishers. Due to its bustling activity in the evening, the Navigli area became the scapegoat of the Italian media and politicians during the brief pauses from the city’s lockdown, a litmus test of the effectiveness of the measures taken and measure of its citizens’ supposed moral laxity.

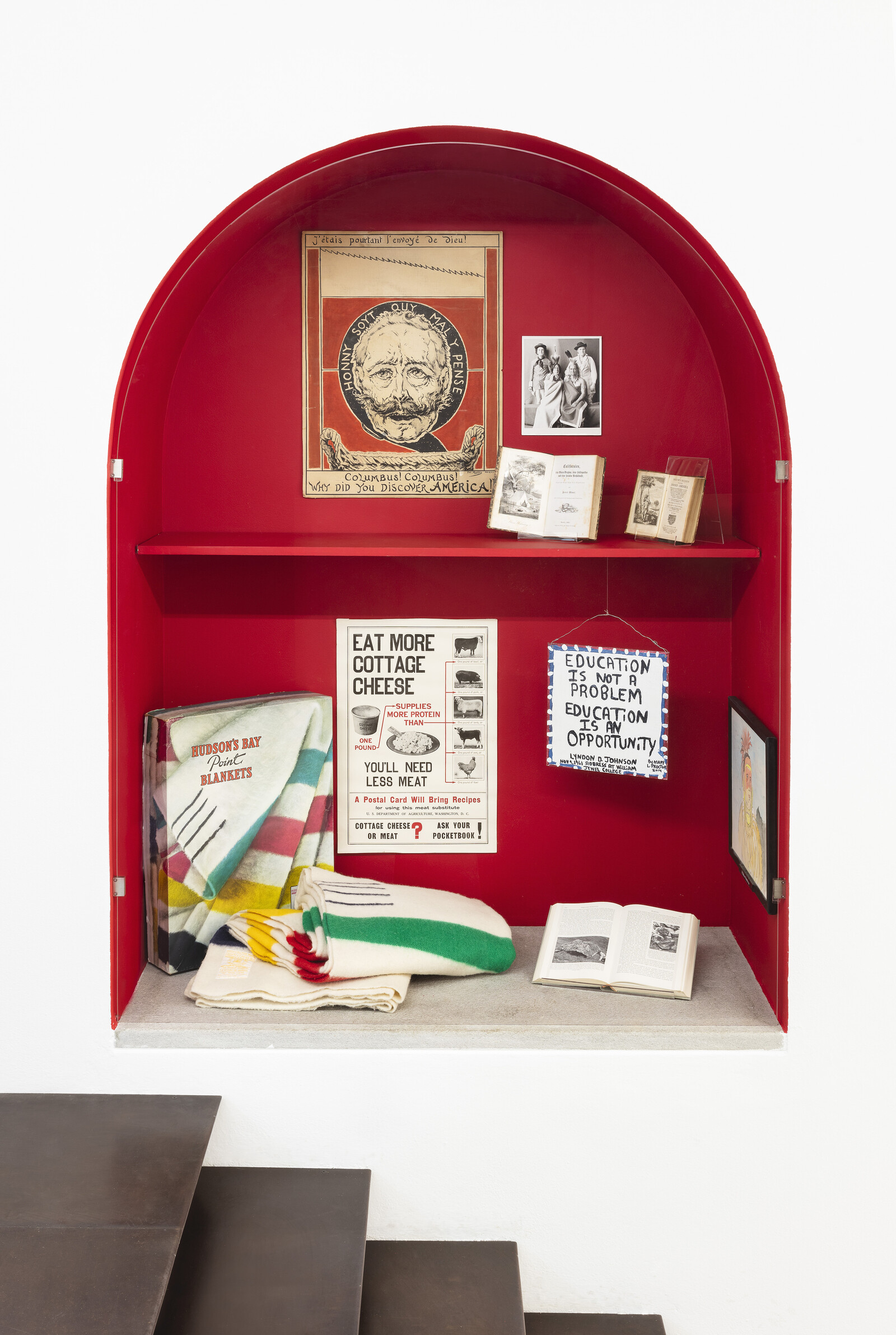

Near the exhibition’s entrance is a display case containing Americana that the artist collected on e-commerce platforms and via donations from friends—memorabilia, posters, and books that offer a deliberately naïve record of the foundation of the United States, omitting the less idyllic aspects of the story. This arched and recessed alcove, the interior of which is painted red, is inspired by Bosmans’s fondness for the étalages common to Northern European countries: street-facing windows used to display private collections to passersby. Bosmans’s version materializes an implicit mythology based on exoticizing curiosity and a spirit for adventure that, from today’s prevailing moral standpoint, is overtly partial, antiquated, and problematic.

The seeming gullibility of this work is deliberate. As a mode of collecting and display, it recalls the Italian writer Pietro Citati’s description of Marcel Proust: “What fascinated him was the idea that these objects could be solidified feelings.”1 The solidified feelings on display here—sugar-coated, nostalgic versions of the birth of the nation partly provided to the artist by friends—feel chosen to indicate a broader critique: that at the center of every collection there are passions, individual choices, and arbitrary occurrences that challenge the alleged “objectivity” of art institutions.

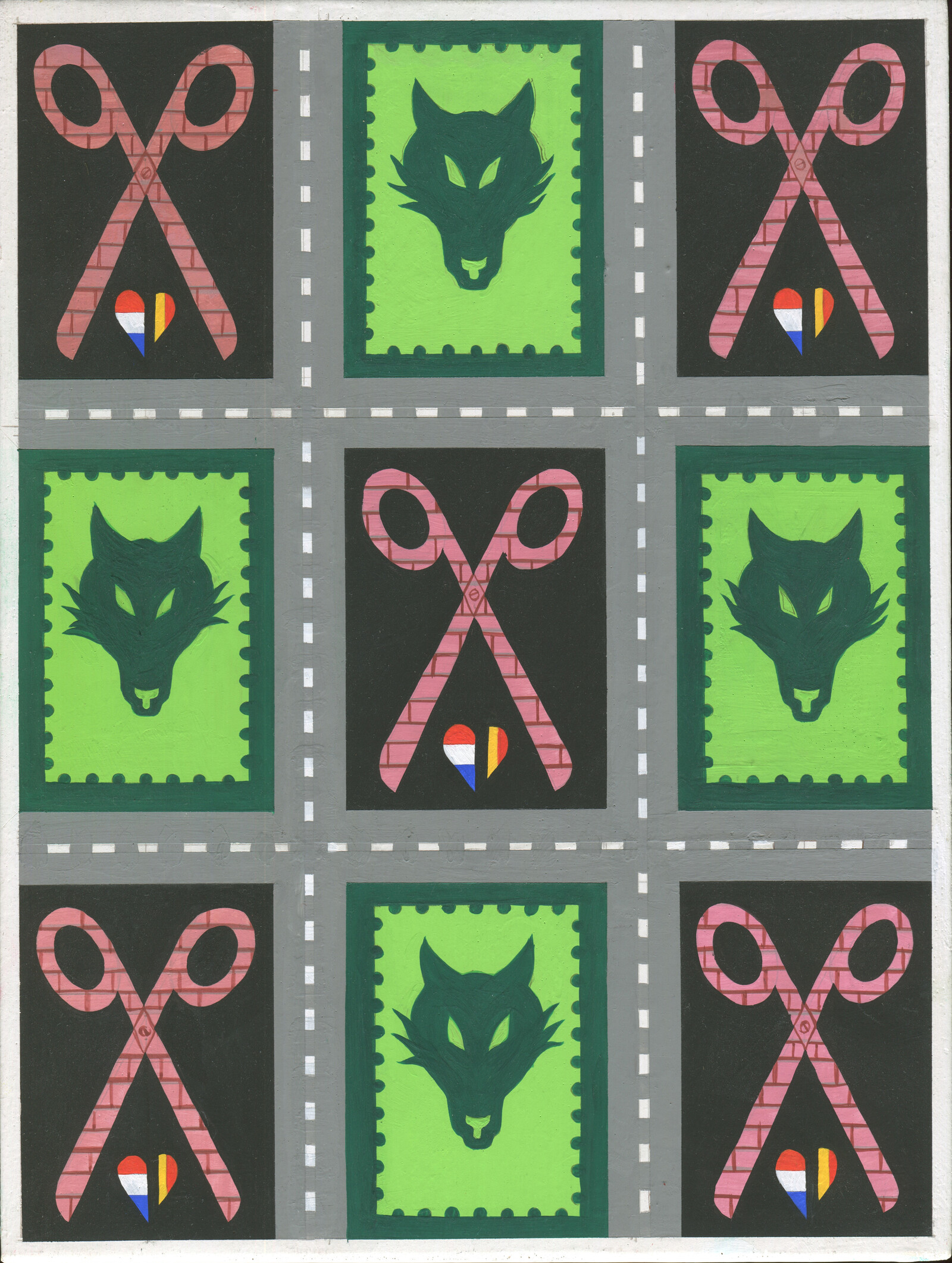

On the floor, a painted path with a heraldic-looking pattern featuring a pair of scissors, houses, and wolf heads refers to the current EU policy in which animal reserves are being replaced by habitat corridors that allow animals to migrate safely (Wolf Corridors & Stamp Forest, 2020). This shift is less aesthetically satisfying for hikers, but as a wildlife protection strategy it is more suitable to the behavior of several protected species. Bosmans reads this switch as part of a broader process of de-objectifying animals within enclosed frames, one that also provides a means of contemplating other species.

On the final wall of the exhibition are three works from Bosmans’s “Legends” series of small gouache and silver-point allegorical paintings that, as the name implies, contain a set of indexical references to the exhibition’s underlying themes, and to the location hosting it: the wolf head symbol from Wolf Corridors, fake stone walls, stylized highways, a door left ajar. Synthetic and emblematic, these works express the artist’s interest in folk art and decoration. The fil rouge of the show is now coming together: “A Perfect Shop-Front” stages the complex intersections of desire, taste, control, and (sometimes unconscious) systematization that run through the history of art institutions. Rather than present a critique, Bosmans draws connections between objects and experiences to reveal the codes that underlie institutional forms of production and display.

Pietro Citati, La colomba pugnalata (Milan: A. Mondadori, 1995).