“This is a stupid town. It’s lazy, it’s polite, it’s so sissy in its mentality, so go along with everything that goes along. It’s corporate-owned, it’s a town owned by Hollywood, and it’s about time it grew up. It’s about time that it took art and said come on baby, show me something!” Thus spoke John Cassavetes in a behind-the-scenes documentary for his 1977 film Opening Night. The clip played as part of an intro bumper at Now Instant Image Hall, a microcinema in Highland Park with a bookshop selling various zines and small press titles related to its eclectic programing, from Susan Cianciolo’s films to historical gems like Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles (1972). The latter screened just a few days before the cultural Leviathan known as Frieze Week descended upon the city, bringing with it a deluge of rain and the attendant disenchantment.

Cassavetes’s diatribe drew laughs and cheers from the 60 or so rain-soaked people nestled into the space (I love the way he hisses out the word sissy—his hatred for Los Angeles is unimpeachably authentic) and it does presciently, if cynically, encapsulate this moment of arrival. The LA art scene grew up. Or at least, the kids stacked two-by-two threw on a trench coat and did their best. I eased into the week by starting at Now Instant, mostly to see the short documentary Charlie’s Lot by journalist and filmmaker Tom Carroll, about Highland Park local Charlie Fisher and his Sisyphean routine of storing and maintaining his 28 cars (the “lot” refers to a public parking lot where Fisher spends hours shuffling his cars around to avoid parking tickets).

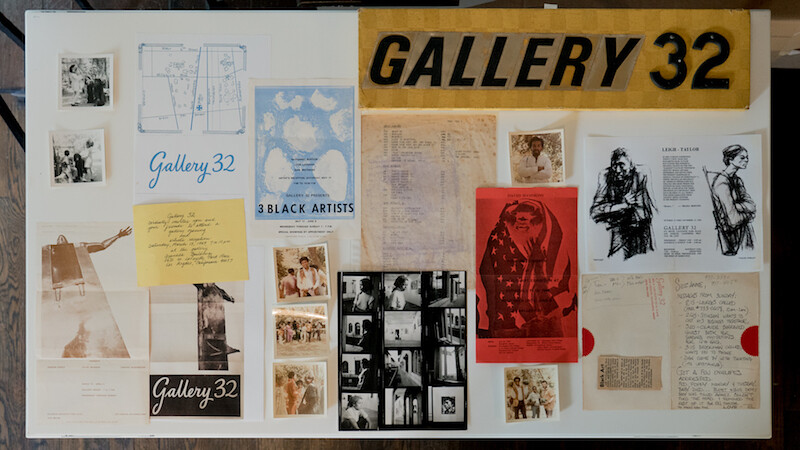

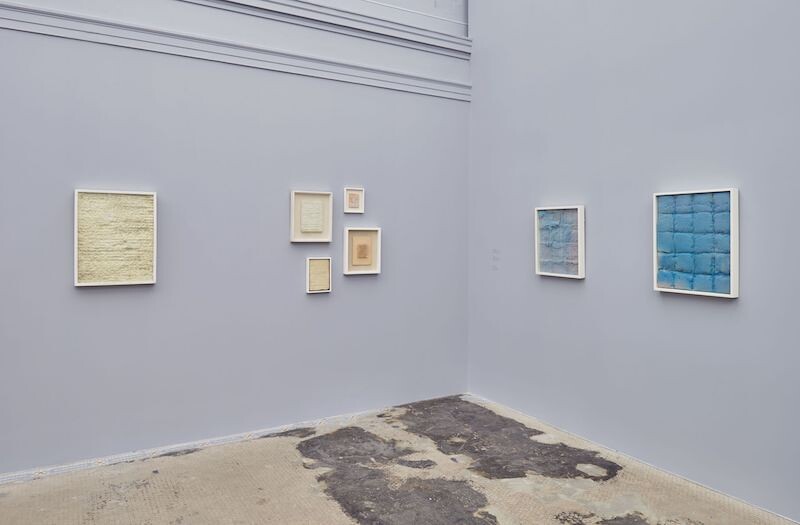

Among the gallery openings I caught in the days leading up to the fairs, O-Town House gallery in Macarthur Park opened a solo show with Suzanne Jackson, who in the late 1960s ran Gallery 32 out of the same location, a white-stucco complex called the Granada Buildings. The show focuses on the patient, impasto-laden paintings Jackson made over the past decade on scrunched and folded canvases, shown along with ephemera from her gallery. At Hauser & Wirth, the sober sensuousness of Piero Manzoni’s “achromes,” paintings without color from the late 1950s and early ’60s, are given their full due in “Materials of His Time.”

The newly opened Allen Ruppersberg retrospective “Intellectual Property 1968-2018” at the Hammer Museum captures much about what LA did so well when no one was looking. Ruppersberg synthesized a ratty beatnik sensibility with the humor of West Coast conceptualism, then threw in some NYC-inflected literary gestures for gravitas, all while keeping a hand in the illustrative obsessions he honed in the Midwest. His 1968 Untitled (Canvas Aquarium) is a humble-looking aquarium fitted with lights and filled with nothing but a few inches of gravel and a blank white canvas. Evoking a diorama, a desert soundstage, and the performative isolation of the painter’s studio, the little box concretizes a certain Tinseltown miasma while keeping the artist safe from its fumes. It’s the kind of work that happens when artists in LA are free to distance themselves from Hollywood. Now, as talent agencies are representing blue-chip artists pursuing commercial entertainment projects, the “vibrant energy” (to quote every press release related to this week) that emanated from the tense standoff between art and entertainment has cooled into a limp handshake. In 2016, Endeavor, parent company of the talent agency William Morris, purchased a majority stake in Frieze, describing it as a “leading arts media and event company.” That year Endeavor also hoovered up IMG, a management company representing luminaries from the worlds of sports, fashion, YouTube, and so on, as well as UFC, the Ultimate Fighting Championship, purveyor of the free-for-all combat spectacle known as mixed martial arts. Not long before the acquisition, UFC inked an exclusive 70-million-dollar contract with Reebok, effectively barring its fighters from securing their own endorsement deals while sending them into the ring as independent contractors with zero health benefits.

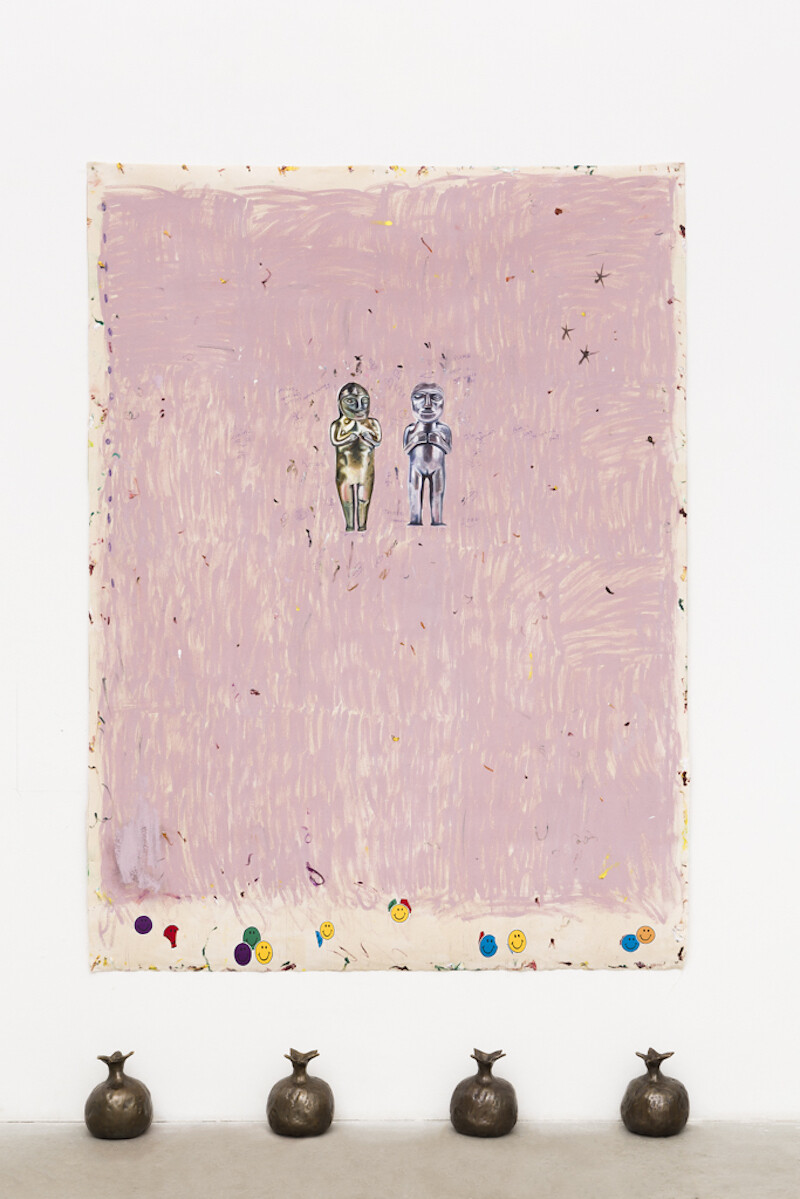

My beeline through the booths during the VIP preview of Frieze LA was a blur of greatest hits, although I was happy to see some unframed Vivian Suter canvases hanging like bruised and bloodied banners in the booth of local gallery Karma International, and actually stopped short at Paulo Nimer Pjota’s paintings juxtaposed with bronzed and found objects at São Paulo’s Mendes Wood DM. The façades that make up the storied Paramount backlot are not equipped for inclement weather, and several of the site-specific commissions, including Tino Sehgal’s This is Competition and Karon Davis’s installation Game were shuttered or moved elsewhere. But Trulee Hall’s Frieze Project installation Infestation remained unharmed by the rain. The giant acid-bright green tube wending its way in and out of the doors, windows, and fire escape of a tenement building façade, made for an uncanny semi-creature somewhere between an unspooled neon sign and a snake with no head, just tails at each end. Its campy, ruinous look worked particularly well among the ad hoc ruins of the dampened backlot.

Over at satellite fair Felix, held at the Roosevelt Hotel in Hollywood, the throngs of people wending their way around the 11th-floor rooms where galleries took up residence, had a bit of a flattening effect for taking in the work, like being trapped in a posh MC Escher–designed house party. In New York gallery Marlborough Contemporary’s room, Matt Johnson’s carved wood sculpture Black Hole Pizza Box (2018) is exactly what it sounds like—a humble cardboard-looking pizza box whorled into a spin of color funneling down into nothingness. It has the material control of classicism and the retinal pleasures of a stoner’s pop-science musings. Many galleries made the mistake of filling their narrow hallway entrances with giant paintings that were impossible to take in from butterfly-kissing distance, which is exactly why Alexandra Noel’s tiny five-by-seven inch diptych Plan A and Plan B (2018) jumped out at New York gallery Bodega. The pastel-colored houses (duplexes?) are depicted with the flat compositional style of Walker Evan’s forays into paintings, but rendered in super crisp, bougie lines that still read as ironic. In his LA documentary, Banham declares that great cities are capable of imposing a kind of style upon the rest of the world. Sometimes that style gets imposed back upon Los Angeles in the form of naive fantasy, or tired iconography. Noel skirts both.

Spring Break art fair took place in a former fruit depot downtown and felt the most uneven. A suite of Ben Wolf Noam’s dreamy watercolors housed in aluminum frames faced a row of his charcoal sketches on cardboard at the booth of Newgate Gap from Kent, UK. They have a certain punk anguish, like nihilist carvings on a high school desk, rounded out with Picasso-esque figures that ultimately betray control instead of frenzy. LA-based Marathon Screenings series showed Maura Brewer’s latest film Jessica Manafort (2018), which traces the compelling, if inscrutable, flows of capital between the young filmmaker Jessica and her father Paul, the recently convicted former campaign manager for Donald Trump.

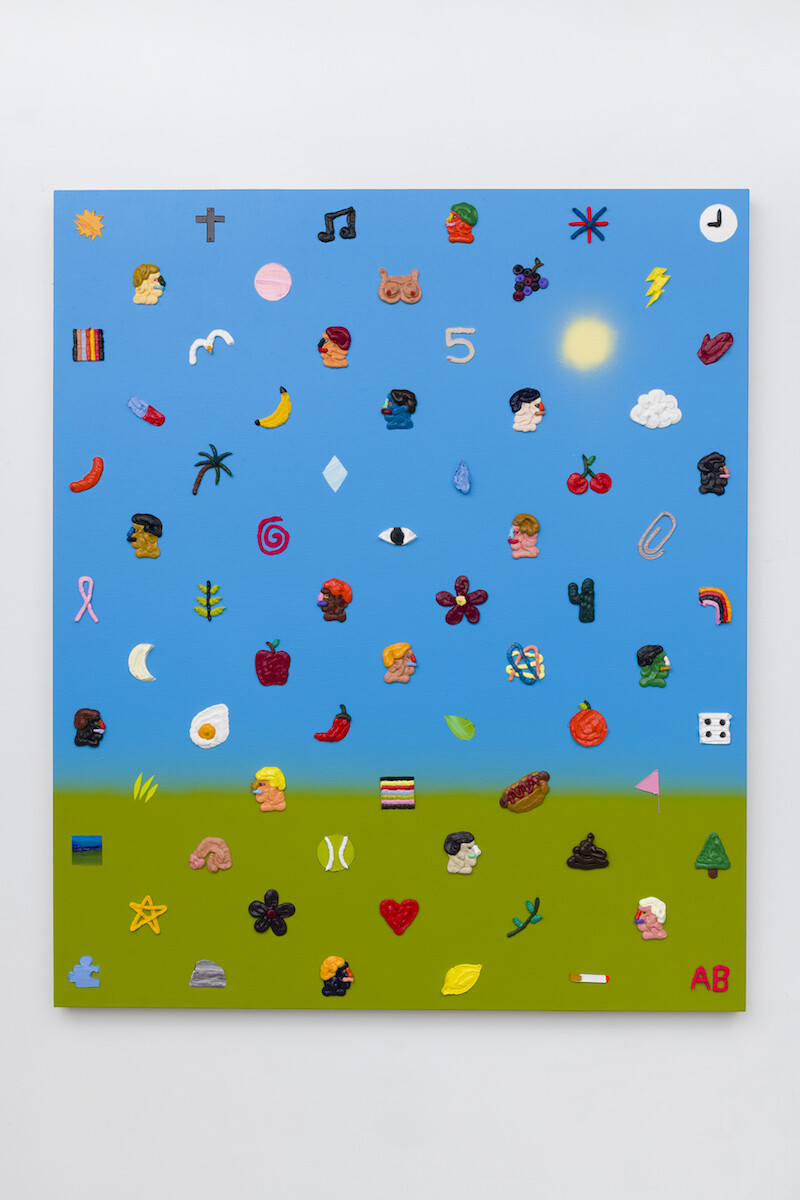

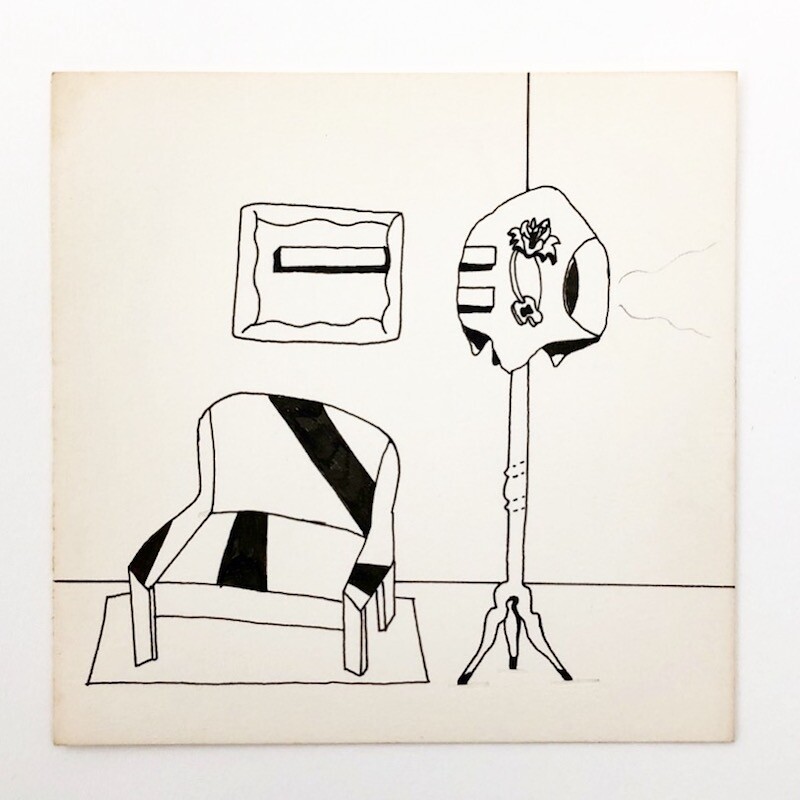

Art Los Angeles Contemporary, which had been unceremoniously relegated to the status of satellite fair, on its tenth anniversary no less, was the one fair where I was truly moved and surprised by some of the work on view, as the vacuum left behind by mid-level galleries abandoning ship to get their toehold in Frieze or Felix was quite nicely filled by smaller, newer, and unfamiliar spaces. Adam Beris’s paintings brought by local gallery Ochi Projects are grids of silly icons—a bird, a cock, a flower, a face—applied straight from the tube. They have a lighthearted thingness that seems farted out from a busted 3D printer. London’s Vigo Gallery showed just three of Johnny Abrahams’s attenuated monochrome paintings, all titled Untitled (Dark Blue) (2019), their curving geometries smartly offset by one of Amir Nikravan’s slightly gastric-looking abstract sculptures. Venice Beach gallery As-Is covered their booth with small, extraordinary Philip Rich ink drawings from the 1960s, casual bodies and domestic scenes with a surrealist twist: Ken Price, but distilled. The booth itself was manned by Bruce L. Kates, trustee of the Rich estate, who was also the artist’s caretaker at the end of his life.

This week will happen again, and again, and every time we’ll snap to and fumble to find our place in it, and when it leaves things will go back to a calmer, lighter, and more quotidian form of enchantment. Whatever it means for management companies and big galleries will always be somewhat at a remove from those who still create like no one is looking. As comedian Maria Bamford said during an Art Center graduate seminar with writer Sarah Lehrer-Graiwer, “Just find a way to do your work…. Look, I tremor. And I’m a millionaire. Who gives a shit.”