Whirlpools of words, sans-serif swirls: language is both subject and material of Ferdinand Kriwet’s exhibition at Georg Kargl Fine Arts, part of this year’s curated by_Vienna.1 In some of Kriwet’s text-based works, the typographical forms take clear precedence over linguistic sense; in others, the words’ meaning packs the stronger punch.

“KRIWET” explores the multidisciplinary, multipronged, and until recently underexposed oeuvre of German artist Ferdinand Kriwet, whose practice began in the early 1960s. Back then, at the age of 19, he produced his first “Hörtexte” [aural texts]; proto-podcasts in which meaning was obscured, the sounds and phonemes creating a sonic collage. Over the following decades Kriwet would return to expanded notions of collage and experiment with words-as-visual-material in mediums as varied as pencil on canvas, aluminum signage, wallpaper, even a series of oversize artist’s books.

Curated by Gregor Jansen, director of Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, this exhibition is essentially a mini-retrospective whose choreography immerses the viewer in the artist’s practice. Viewers are drawn in from the street by Campaign (1972–73/2005), an image-sound collage projected outward through the gallery windows, which here act as giant television screens. Kriwet collages black-and-white TV footage of Richard Nixon and George McGovern’s 1972 US presidential campaigns with broadcast news and advertising; inside the space, the sound-bites blare in scratchy 1970s audio.

Although Kriwet is best known for his video and audio work—his many Hörtexte were broadcast on German radio in the 1970s, and his seminal video Apollovision (1969), not on view here, focuses on US media reaction to the first men on the moon2—the rest of Jansen’s show focuses on the artist’s exploration of text as image (a perfect fit for Curated by_Vienna’s theme “image/reads/text”)—the artist, it must be noted, primarily considered himself a Concrete poet. The oldest work is Typo-Collage (1961); installed alone on one wall, this small-scale rhythmic collage of strips of typed words on paper (arranged vertically with negative space) sets the stage. More word experiments line the walls of the following rooms, including a series of “Rundscheiben” [round slices] which comprise black-and-white lines of text in jagged circular formats (reading here is a game of deciphering, though many of the texts defy interpretation). A series of pencil-on-canvas works, mostly from 1976, presents letters and words in faint, weblike layers.

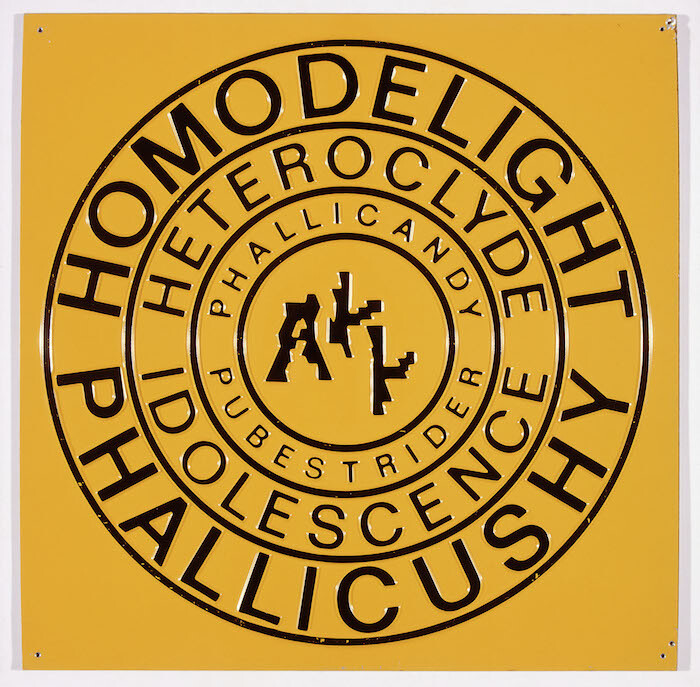

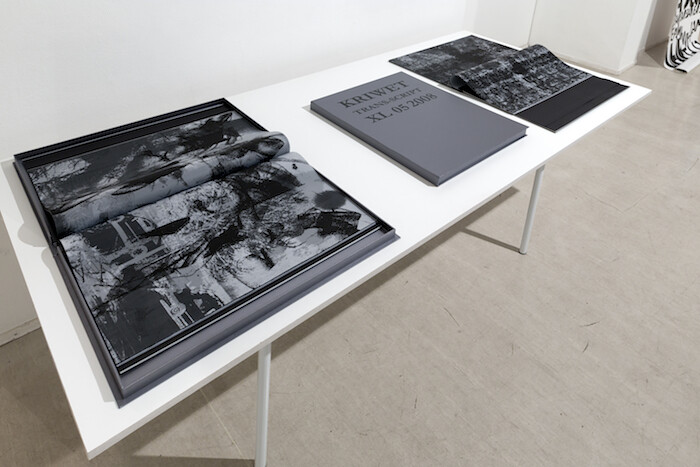

In the gallery’s largest space, a vast, subterranean, skylit room, a series of nearly 80 oversize book-objects entitled “Trans-Script” (2005-10) is displayed in a wooden case (they’re not to be touched but facsimiles of the books, filled with text collages, are available in the adjacent reading room). Here we also see Kriwet’s large-scale works in color—in which language’s meaning seems once again to take priority over its form. The artist plays with words in his aluminum Text-Signs, teasing us with provocative portmanteaus like “Phallicandy” or “Sadomasorry.” In the middle of the room hangs a transparent PVC sheet printed with a bullseye of thick black letter-words, again in concentric circles, forcing us to decode fragments like YUM YUM in a kind of find-the-words game.

The breadth of his “other” activities meant that Kriwet wasn’t always accepted by the German art establishment. An autodidact, he set up sound and light systems in nightclubs, created neon works (not on view in this show), took a self-imposed 20-year break from art starting in the late 1980s. Near the gallery desk are copies of his 1961 novel Rotor, and a vintage record player upon which his LPs (the vinyl surfaces also printed with words) are displayed; alas, no one can get the turntable to work.

Perhaps one reason for Kriwet’s neglect is that he was ahead of his time. His video collages (including Campaign and the aforementioned Apollovision) follow a jump-cut format overfamiliar to us now, but which in the early 1970s was radically fast and fragmented. The snappy, snarky messages on his aluminum signs foreshadow internet memes. The meters-long, undated wallpaper work Tapete on the gallery’s back wall—a large grid of images of American road signs, neons, and 1960s and 1970s brand names—comes straight from era-appropriate Pop, but also recalls the image sequences found on Instagram. Through it all are Kriwet’s subtle critiques of media, its distribution systems, and its effects on our politics, economics, and most of all our perception. “KRIWET” reflects an artist who dared to combine not only ideas and aesthetics but also art and life in a way that remains kaleidoscopic, compelling, and nonlinear.

Curated by_Vienna is an annual fall “gallery festival” sponsored by the Austrian capital’s economic department section responsible for creative industries. For one exhibition rotation, an outside curator works with one local gallery—this year, 21 spaces participated—creating a show on a predetermined theme.

Apollovision also exists as an audio-only piece and a book; Kriwet referred to the video as a “sound picture collage.”