Though not officially a part of the exhibition, the enormous black-and-white photograph on the exterior of the Henry Moore Institute—the image also appears on promotional material—anticipates the works shown inside. It depicts four Black women posing and gesturing playfully by some rocks on a beach. The women are a part of Lungiswa Gqunta’s family, and the photo was taken in mid-1970s South Africa at the height of Apartheid, when the best parts of the country’s vast coastline were delegated for the use of white people only. With this additional information, the photograph captures a moment of resistance, pointing to one of the many ways in which Black people reclaimed their rights to access, freedom, and movement.

Gqunta was born in 1990, four years before South Africa held its first democratic elections with universal suffrage. This period may have brought an end to the legislative system of Apartheid, but its effects endure—a point to which she constantly returns in her practice. This economical show opens with Zinodaka (2022), an installation that takes up the entire floor of the first room, meaning the visitor has to walk over it to get to the other galleries. In the work, a thin, patchy layer of sand covers a cracked clay floor that Gqunta walked over for hours to get the contours just right before the drying material set: the more textured the surface was, the more unstable it would be. Blue glass sculptures resembling rocks or shrunken water bottles pepper the surface, apparently at random. The weight of my feet over the sand and clay summons slightly grating sounds, and I am immediately aware of how I am impacting the surface and how those effects will be compounded over the course of the exhibition as it bears witness to the people walking over it. Gqunta wants visitors to be conscious of their presence as they move through the uneven space, evoking—if only for a few minutes—the lived experiences of Black people who had their movement regulated in Apartheid South Africa.

The artist’s multidisciplinary practice is connected by her attention to materials, in particular the ways in which they evidence the legacies of colonialism. In the next room, cloth is wrapped around miles of barbed wire to form Ntabamanzi (2022). The sculpture looks like two waves crashing together or the entrance to a mountain, which fits its title, a portmanteau of two Xhosa words: ntaba [mountain] and manzi [water]. The work’s materials and positioning again force the viewer to be self-aware and careful of their body’s movements if they want to avoid getting caught on the exposed barbs. The blues and whites of the different cloths call up the various blue tones of the glass sculptures in the previous room and propose water as one of the elements—with clay and air—to be reclaimed. Bunches of coins are hung throughout the sculpture: these are stand-ins for offerings given to large bodies of water when traditional spiritual practices were more widely observed in South Africa, legitimizing alternate sites of knowledge and ways for it to be created and shared.

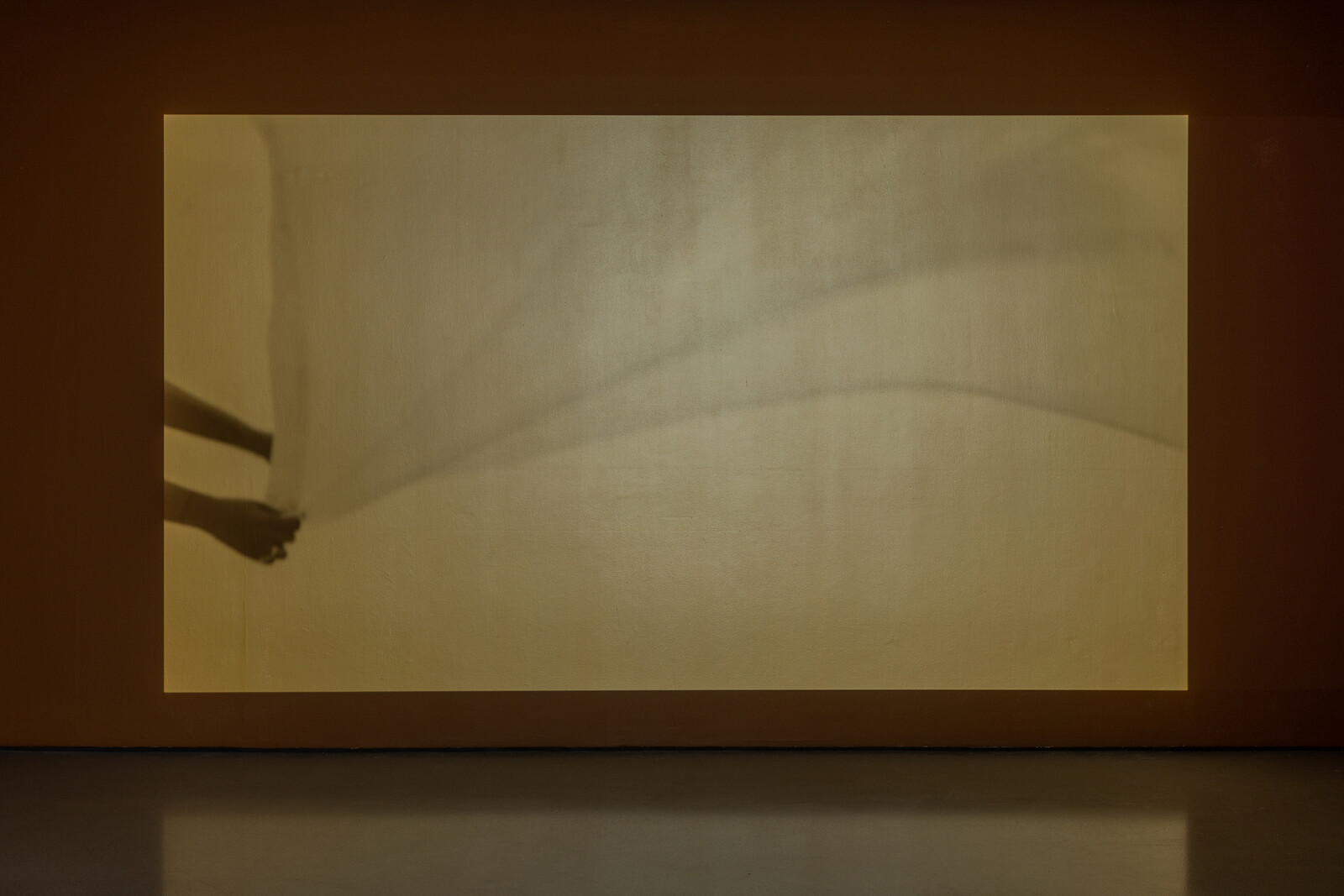

The last work, shown in a screening room at the end of the exhibition, directly references Apartheid legislation. The Riotous Assemblies Act was drafted in 1956 to prevent gatherings in public spaces “if the Minister of Justice considered they could endanger the public peace.” Gathering (2019) is a 15-minute video showing a sheet in the process of being folded by two people whose bodies appear in frame at intervals. These seemingly mundane tasks allowed people to meet and exchange information without raising suspicion under the oppressive regime. The song that accompanies the footage, “Yakhal’inkomo” [The bull cries], may be a soothing tune akin to a lullaby but its lyrics deal with the collective pain of Black people during this time. This contrast between these references to subjugation and ways of resisting is a running theme of the exhibition. “Sleep in Witness” is as much about making palpable the violence of existing and surviving under these conditions as it is about transferring the hope that presents itself in the moments of refusal and resistance.