By rights I shouldn’t be writing this. I should be on the streets of São Paulo, beer in hand, as carnival rages around me. The bloco—street party—that passes under my window is a queer one. There would be a lot of kissing and not a lot of clothes. Instead, the Lenten celebration cancelled, my neighborhood is as quiet as the downtown of Brazil’s largest city can be. There is no samba band playing in the square, there are no sound systems blasting favela funk morning to night, no messages from friends recommending parties in other neighborhoods, no chance to go to the Oscar Niemeyer-designed Anhembi Sambadrome just north of here. I could be watching the carnival schools—there are over a dozen based in the city—parade through that 103,200-capacity stadium, the storyline and costumes of each a year in the making.

There’s a popular meme here that describes images and situations as “Sad and Brazilian.” For all the contemporariness of its dissemination—it’s shared on social media and in sprawling WhatsApp groups—the phrase taps into the deeper cultural concept of saudade, which describes a longing for something lost, perhaps never to return again, apt for a country founded by slaves, colonialists, and immigrants. The saudade for carnival now hangs over this Brazilian summer. Not only has it pushed many into even greater economic precarity—the hawkers selling beer and water from icy cool-boxes, for example, would in normal circumstances make a couple of months’ worth of income in a week—but it is a further psychological blow to a country already battered by the pandemic. “We all have carnival as a source of total or partial income,” a choreographer told CartaCapital, a weekly journal. “And worse, carnival is a movement that heals us from the beatings of everyday life.”1

Julia Lima, a curator, recognized that what she would miss most was the simple pleasure of bodies coming together on the street. “It is the best of Brazilian culture,” she tells me in the Centro Cultural da Diversidade, an LGBT-orientated arts venue which plays host to the one indoor element of the show, “it’s a time when we are all on the streets, a communal moment.” Her response was to organize “Ninguém Vai Tombar Nossa Bandeira” [Nobody Will Drop Our Flag], an exhibition of flags, banners, and posters hung from buildings and pasted to street walls across the city. “The flag is inherently political,” Lima says. “And so is carnival.”

Strung across the windows of multiple apartments in my block are a series of banners. “Humiliating” reads one in Portuguese, the italicized word depicted in stitched red sequins. “Denier,” reads another. “Rotten.” Titled Pra quando o carnaval chegar [For when Carnival comes] (2021) they are the work of Nara Rosetto and flap in the wind, leaving little doubt as to whom the protest is aimed at. Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right president, won’t be mourning the loss of carnival the way most in Brazil are: he was frequently the subject of criticism in the parades, and has done little to protect the country from the ravages of Covid-19. In 2019 he hit back by posting on Twitter a since-deleted video, taken at a bloco and featuring one reveler urinating on another, with the caption: “This is what many street carnival groups have become in Brazil.”

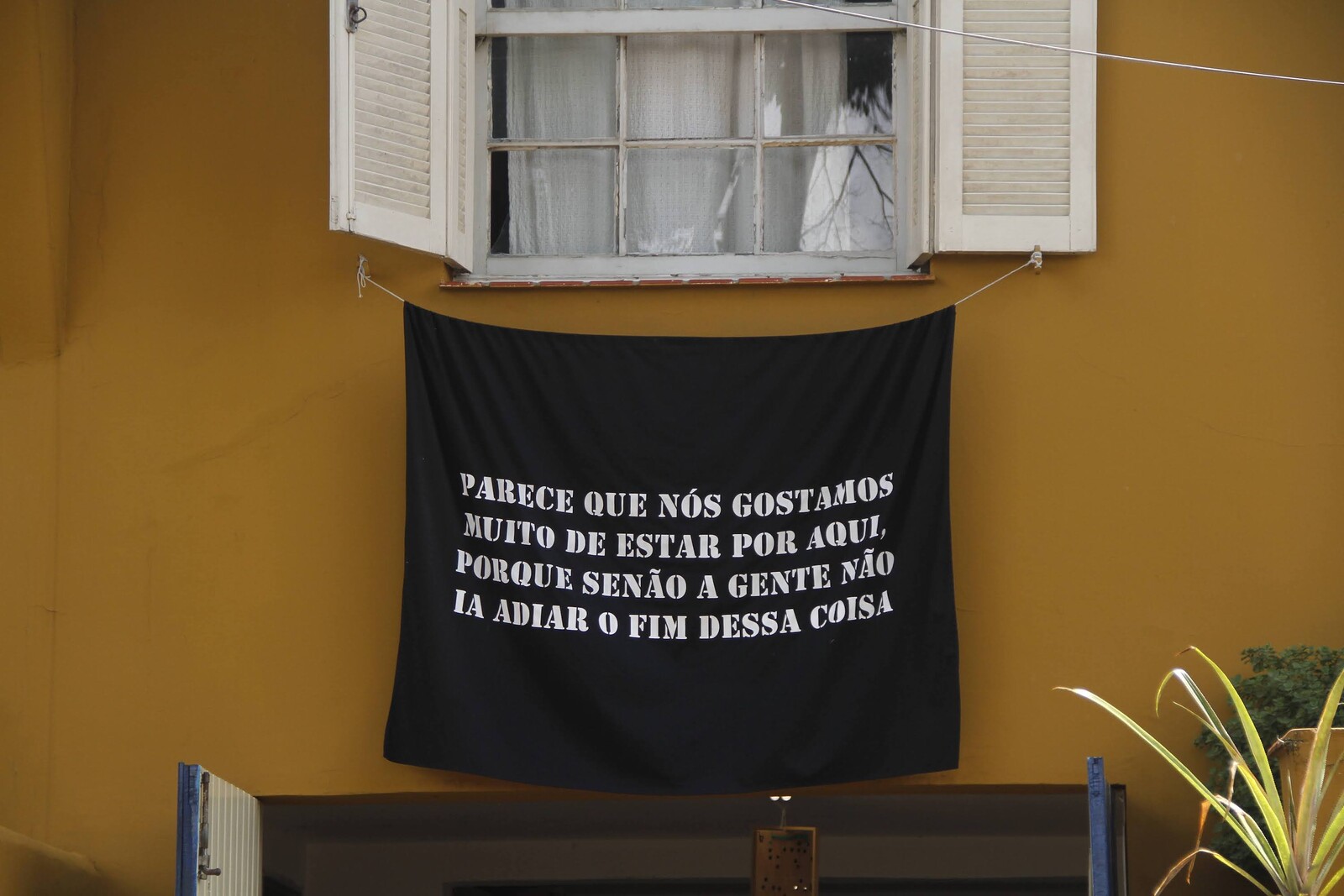

The shame that those who oppose Bolsonaro feel when the leader of their country uses such rhetoric is obvious in two works that utilize the Brazilian flag. In the center of the city I come across the familiar green, yellow, and blue national standard hung from a flexible metal pole bent back on itself to touch the pavement it is installed on, the flag trapped under the base to hold the tension of this street sculpture. O cinismo da certeza [The Cynicism of Certainty] (2021) by Felipe Cidade prods at the absolutism of far-right politics and its co-opting of national symbols. Likewise, a version of the flag on a wall at the Centro Cultural da Diversidade, stitched from scraps of sequined material by Tomie Savaget and titled Símbolo Nacional Pregado Com Fita Adesiva [National Symbol Nailed with Adhesive Tape] (2020), mournfully hangs from a single point, a fallen symbol. Many of the works in the show are didactic to the point of simplicity: from her “Classifieds” series (2014) Salvadoran artist Abigail Reyes flyposted the phrase, translated from the Portuguese, “I had the right to say no”; Alan Ariê put up 44 instructions for anti-racist actions (44 Práticas Antirracistas, 2021). More opaque are Aglomerado [Agglomerate] (2021) by Leka Mendes, a black flag containing a rough silver circle, a motif akin to a imploding star; and Kauê Garcia’s gloriously bizarre photo-printed banner featuring a closeup of self-styled Bond villain Elon Musk’s mouth (Nação (Elon Musk), 2021). Yet perhaps directness is necessary when working in the street.

I follow the trail of flags across the city, past botecos and homeless encampments, busy roads and quiet side streets, up into the hills of northern neighborhoods with their gated villas, into the fancy avenues of Jardins and Pinheiros. Along the way I get a text. No recommendations of debauchery, sadly, but a performance in a busy shopping street in which a man is sitting naked on a loose pile of concrete breezeblocks. Earlier this month Padre Júlio Lancellotti, a Catholic priest, had taken a sledgehammer to a sea of cement boulders newly installed under a flyover, which city authorities had placed there to prevent members of São Paulo’s almost 25,000 homeless population from taking shelter. It was a courageous gesture by the clergyman, one that Fyodor Pavlov-Andreevich, a Brazil-based Russian artist with a blue tick on Instagram, now seemed to be gate-crashing for publicity.

Looking at the pictures and videos that made their way round social media, I realize that while Pavlov-Andreevich’s aestheticizing action—not part of Lima’s exhibition—was everything that is wrong with self-proclaimed political art, the artists showing in “Bandeiras,” with their bald proclamations and pared-down visuals, had gone the other way. At its best, a flag represents an invitation to gather a community. As right-wing populism here and elsewhere comes wrapped in the standards of nation states, these works proposed new banners under which one might group. Fluttering across the city this past week, they sought to reclaim Brazil’s liberal identity, and to offer an antidote to the humiliation of present politics and economic woe: street memes imparting their message to the (mostly uninitiated) passers-by.

As dusk fell, I saw one final work, Felippe Moraes’s Samba Exaltation (2021), a neon sign installed in an apartment window proclaiming “Agoniza Mas Não Morre”—which roughly translates as “In agony but not dead”—the title of a 1979 samba by Nelson Sargento. In a moment of national melancholy, down but not out, the power of the work, like the exhibition as a whole, lay in a lack of gloss or pretension.

Alexandre Putti, “‘Estamos abandonados’: Sem folia e sem auxílio, trabalhadores do Carnaval relatam dificuldades” in CartaCapital (Feb 13, 2021), https://www.cartacapital.com.br/sociedade/estamos-abandonados-sem-folia-e-sem-auxilio-trabalhadores-do-carna/.