Once a month, art-agenda and TextWork, editorial platform of the Ricard Foundation, jointly publish a Meta text. Here, Ana Teixeira Pinto reflects on her monographic essay on Pauline Curnier Jardin’s work “The World Inside Out.”

It is a strange thing to be a writer who writes in a language that is not her mother tongue. Whenever I write in English—which is almost every time I write, and I write every day—I feel as if I am wearing heavy gear that weighs me down, slowing my pace. Constrained by my lack of vocabulary and grammatical shortcomings, I feel the text never soars, bogged down by doubt, dangling modifiers, subject-verb disagreements, and too many commas. The discomfort is heightened when speaking in public. The experience always feels like wearing a miniskirt that is too tight and too short: somehow your underwear always shows, no matter how composed you try to appear, you always feel exposed and ashamed (yes, I struggle with body image issues, in case you are wondering about my choice of examples). Writing at least has the advantage of allowing me to hide behind a thesaurus and Grammarly. Over the years, I have developed coping mechanisms. I became a syntax thief, stealing well-formed sentences from others and replacing their verbs and nouns with mine. It’s the work of the flesh-eating bacteria, to strip the sentence to the—structural—bone. The fantasy of the expat writer only works if you are a native English speaker who gets to ride on the coattails of empire.

It never ceases to amaze me how language is so seldom discussed as a barrier when considering forms of discrimination. Only once had I heard an audience member address the problem of racially diverse yet linguistically homogenous panels by asking: “How can I be included when I don’t speak the Queen’s English?” Even a slight accent makes you stand out: YouTube is teeming with videos claiming Ilhan Omar “does not sound American.” After all these years, I still feel (slightly) aggrieved when I think about “International Art English.” Oh, the smug face of privilege, never wasting a breath on what for others involves such heavy lifting.

When I began writing about Pauline Curnier Jardin I found myself mired in further difficulty. I have a strained relationship with organized religion. Growing up, I never encountered spirituality in a non-persecutory form. Born in a Catholic country to agnostic parents, I wasn’t baptized and very rarely entered a church. My relation to Catholicism was mostly imagistic and I clearly recall my sense of unease concerning two recurring images: the tortured body of Christ hung menacingly above every altar and the famished African children adorning the covers of every catholic leaflet, with a white priest placed firmly at the center of the photo surrounded by adoring black infants. As a child, you have no recourse to semiotic theory but you intuit the depravity, the torture, the poverty porn. To this day I cannot bear the white savior optics of works like Milo Rau’s The Congo Tribunal (2017) and though I understand why so many Westerners turn to India looking for a spiritual dimension free from the trappings of social sadism, I could never shake the feeling there is something a tad icky about religious tourism—which is, I suspect, part of the reason I became a materialist.1

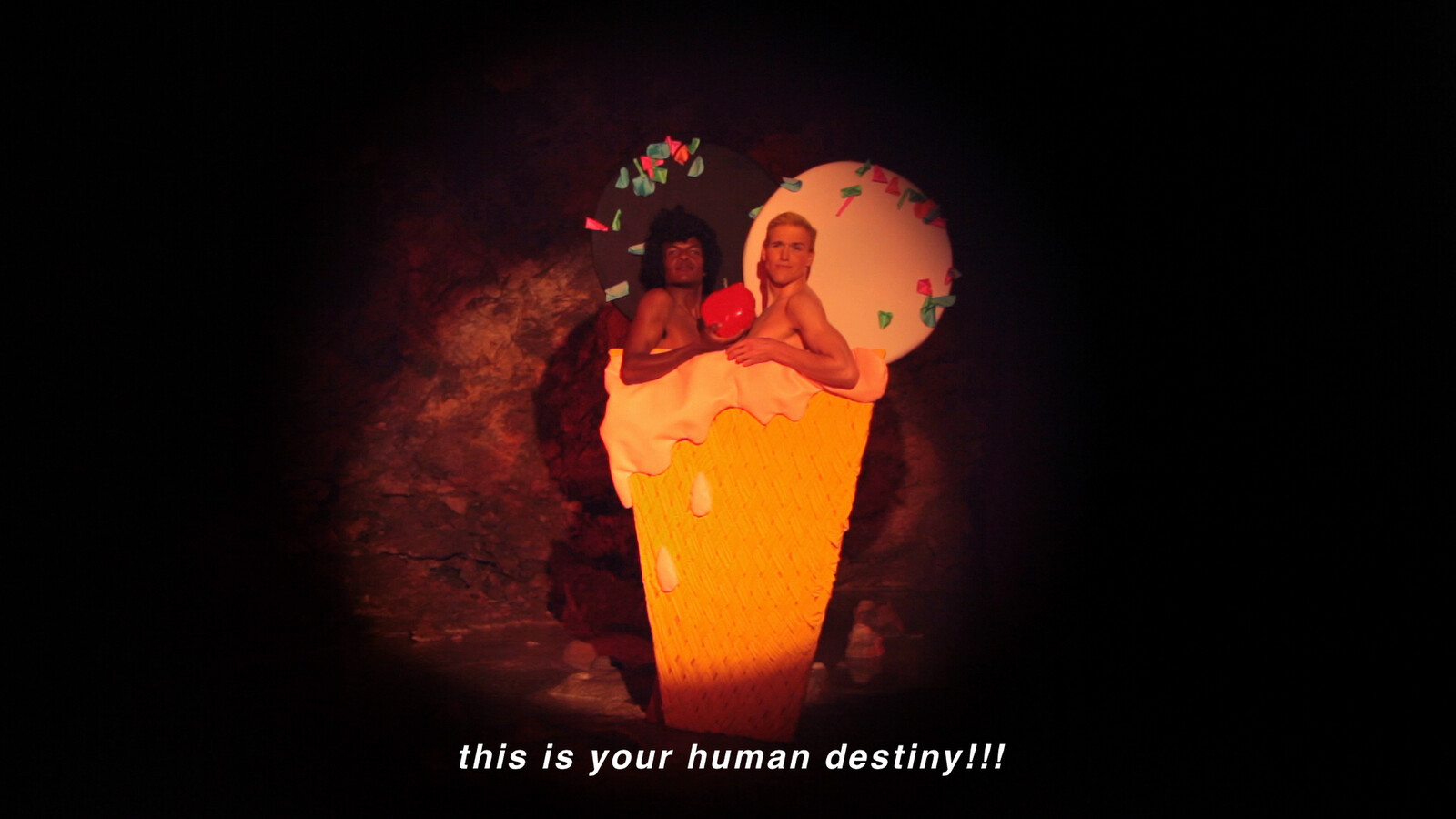

Upon viewing Grotta Profunda, the moody chasms (2011) I felt cast back to old memories: Portugal has its very own version of Marian miracles in the Three Secrets of Fátima, revealed to a child name Lucia, Portugal’s own undernourished Bernadette. Lúcia was held captive by the Vatican after she reported the apparitions and made into an instrument of pro-Nazi propaganda (the Second Secret was the Virgin’s support of the Nazi invasion of communist Russia). To Curnier Jardin, however, the story has a generative potential, it is not a site for denunciation or critique. I struggled to shed my Marxist take, to see Bernardette’s vision not as a symptom (of hunger and deprivation) pertaining to the realm of somatics, but as speech, as a means to express agency and an attempt to articulate her position in a punishing world she did not make or own. In hindsight, I feel I learned something about the aesthetic dimension of life as that which constantly evades institutional capture.

To me the valence of Curnier Jardin’s work extends beyond the aesthetic register, encompassing a broader political dimension, in the way she—obliquely—counters the apocalyptic ethos that came to define our times. Apocalyptic projects, to paraphrase Georges Didi-Huberman, tend to dramatize salvation as the great survival, the epic moment, which will put to death all the lesser, minor survivals, made of pure contingency and devoid of revelatory value.2 From this perspective, the opposite of survival is not annihilation but survivals: the ways people find their footing amid the precariousness of life and manage to somehow make it, in what constitutes a form of endurance without redemption.

This characteristic of Curnier Jardin’s work, her insistence in an asynchronous present and her resistance to the synchronization of lifeworlds imposed by capital, feels particularly crucial at present, at times when the entirety of the political spectrum seems to be marred by a yearning for synchronicity, by the insistence on the question of scale, and the constant appeal to a “planetary” dimension—a dimension that is nonetheless, and malgré soi, wholly identified with the forward-moving time of global development, technological progress, and middle-class reproduction.

My antipathy has not abated over the years, but neither has the Church’s toxicity. As I write this text, a far-right mob is chasing and assaulting teenagers marching in a pride parade in the Polish city of Białystok, under the aegis of, and working in tandem with, the Church. This is a familiar sight: in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the Church led a fascist insurgency responsible for a great deal of bombing and arson attacks.

Georges Didi-Huberman, Survival of the Fireflies (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 40–42.