The Taranaki region on the west coast of Te Ika-a-Māui (the Maori name for the North Island of Aotearoa, or New Zealand) meets the Tasman Sea on three sides and rises at its center to the peaks of Mount Taranaki, a volcano that has been active for around 130,000 years. For the last 50 years, the region’s largest city, New Plymouth, has been home to the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, a contemporary art museum that has exhibited and collected chiefly New Zealand art. To mark this anniversary, Govett-Brewster’s co-directors, Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, who joined the museum last year, invited artist Ruth Buchanan to develop an exhibition of work from the collection. Buchanan, who is based in Berlin but was born in New Plymouth and is of Te Atiawa, Taranaki, and Pākehā (or European) descent, worked closely with the museum staff to install 292 pieces across the museum.

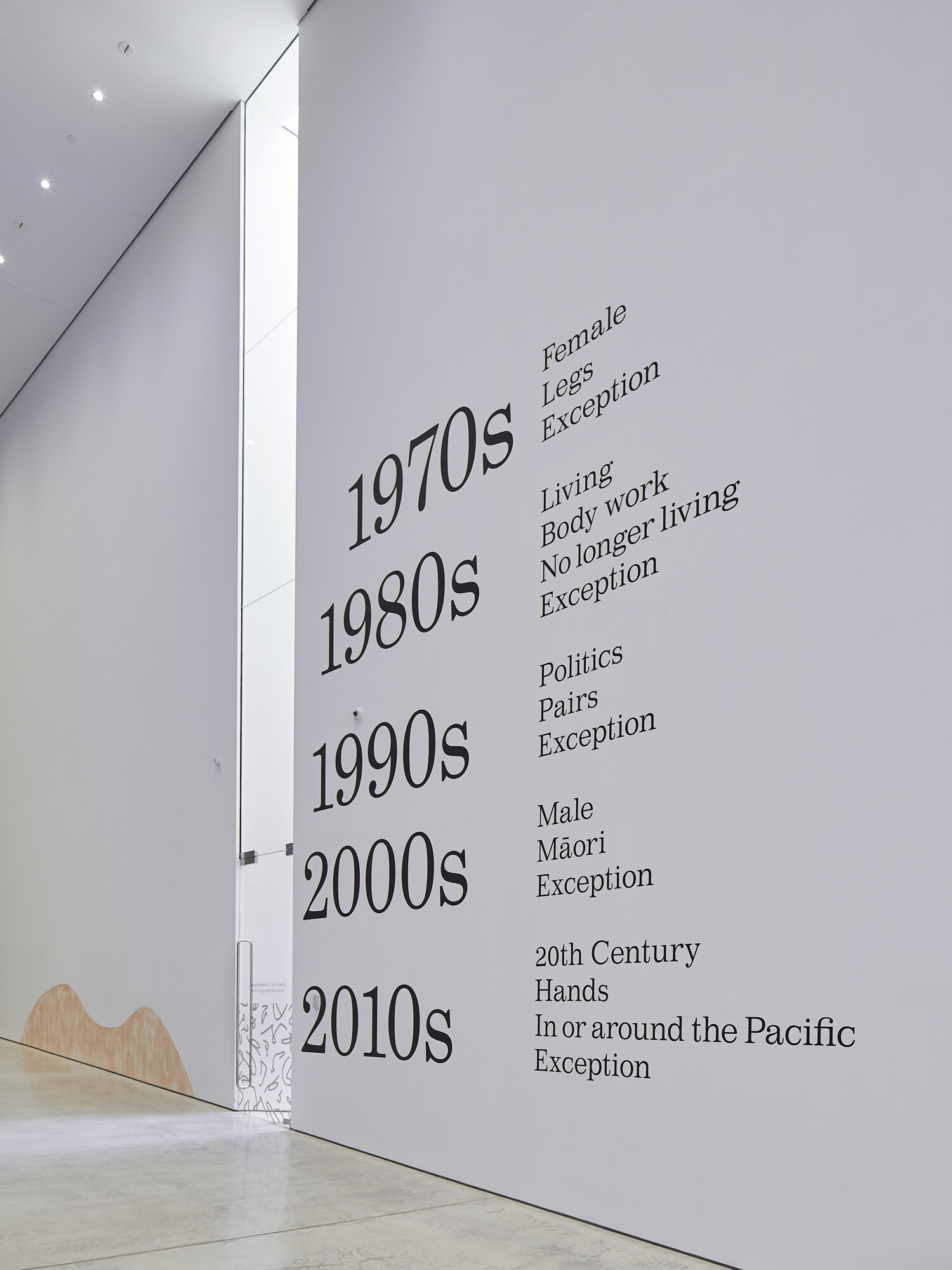

Buchanan is acutely sensitive to language and the body, and these concerns shape her foray into the institution. Her methodology is feminist, seeking horizontal relations, and influenced by Donna Haraway’s “split and contradictory self” and Audre Lorde’s exhortation to “bear the intimacy of scrutiny.”1 Each of the museum’s five galleries is dedicated to a decade in the museum’s fifty-year history, moving from the 1970s to the 2010s. Buchanan has internally organized each gallery using keywords, including “Legs,” “Hands,” “Female,” “Male,” “Living,” and “No longer living.” These labels range from goofy to poignant to revelatory. “Pairs” brings together two works: Maree Horner’s Diving board (1974/1988), a minimalist sculpture pairing concrete “board” and glass “pool,” and Tom Kreisler’s 1 kilo equals 1 pound (date unknown), a photographic screen print showing two piles of sausages, both of which stage a primary relationship between two components. The word “Exception” appears in each gallery, corralling those artworks that don’t fit within the room’s keywords. All the keywords are desperately inadequate to their classificatory or even descriptive task, a failing Buchanan welcomes.

Exquisite pieces are on show throughout the galleries. Ngaahina Hohaia’s Roimata Toroa (2006) comprises 392 hand-woven poi (tethered weights used in performance and dance), embroidered with symbols referencing the region’s long history of passive resistance to colonialism. Or Points of Agreement, for which Tessa Laird hand-copied pages from Len Lye’s Totem and Taboo sketchbook (c. 1925–35) and annotated it with her own marginalia (the Len Lye Centre, where Lye’s archive is held, is housed in the Govett-Brewster). Or the corner featuring textile and ceramic pieces, among them Li’l Mamas Art Klub’s Lalaga (2008), Laurelle Pookamelya’s Ghostnet basket (2011), and Sara Hughes’s World wheat statistics (2011). Or terrific examples of early work by artists such as Fiona Clark, Anne Noble, Fiona Pardington, Michael Parekowhai, Lisa Reihana, Peter Robinson, and too many others to list here.

These galleries are full. Full of paintings skied to the ceiling and hung cheek-to-cheek, art in and under stairwells, and massive works sitting uncomfortably next to small ones, given little of the space to breathe afforded by a conventional hang. This is all deliberate. In conversation with preeminent New Zealand curator Christina Barton on the exhibition’s opening weekend, Buchanan described the galleries as “noisy.” Yet within the cacophony of this exhibition, things are just a tinge awkward or ill-fitting or as if they are not where they are meant to be. The feeling that artworks are meant to be somewhere is, of course, an effect of interpellation that is museological as well as ideological. Museums have long been privileged sites of power and wealth, intended to sort, classify, and narrativize art and its history, while displaying for their visitors a shared set of values.

Power has been on Buchanan’s mind. In her thoughtful, searching essay about the exhibition-making process, she explains that a “core question” for her was: “Where is power now?”2 Power at once structures and is revealed by this (any) collection, and her installation aims to put this on display, in all its imbalance and omission. She cultivates this discomfort spatially through her strict display parameters (“to show the first work acquired per artist, per medium, per decade”), a warts-and-all structuralism that makes apparent certain painful facts, like the collection’s underrepresentation of Māori, women, and Pacific artists.3

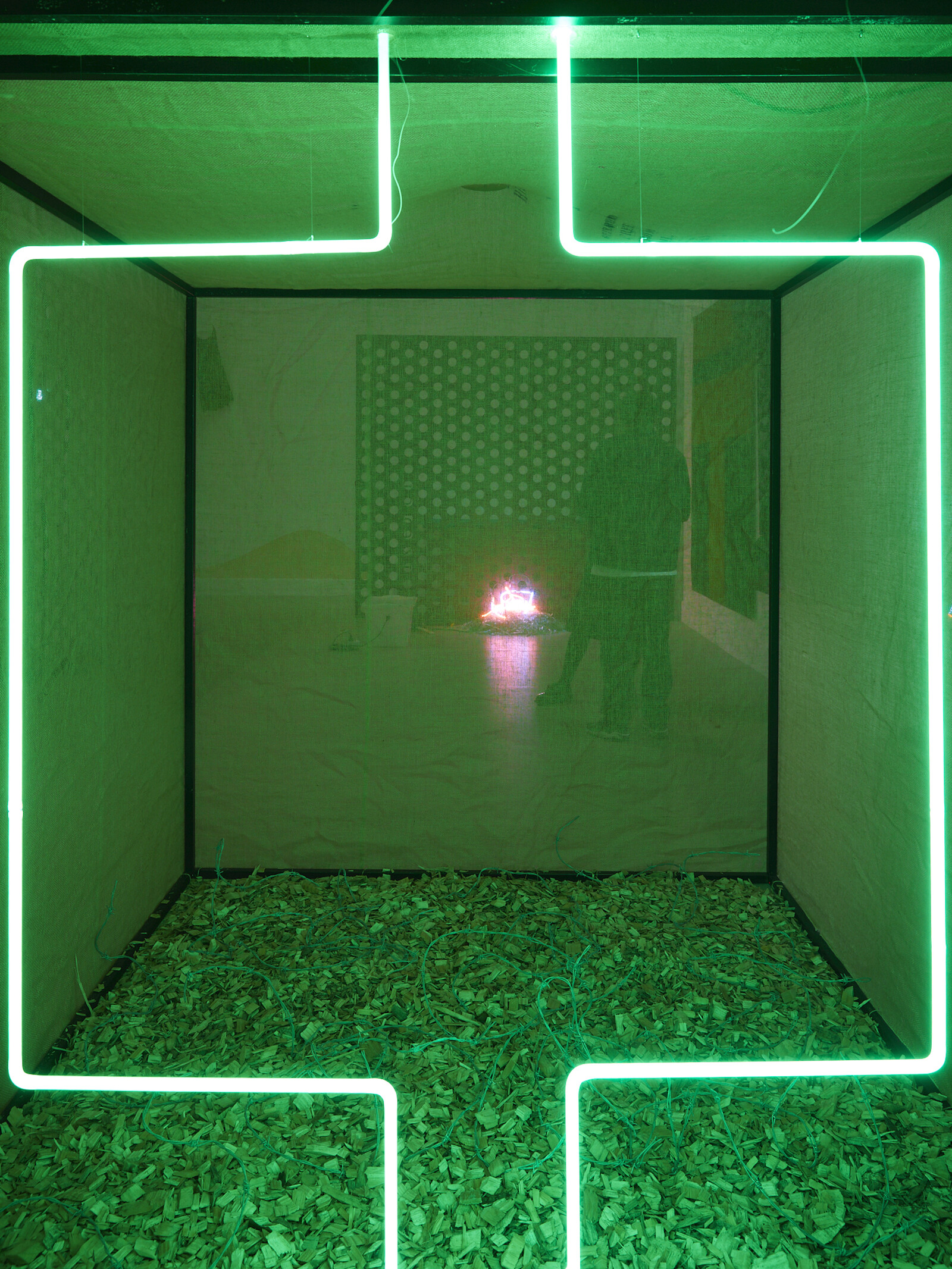

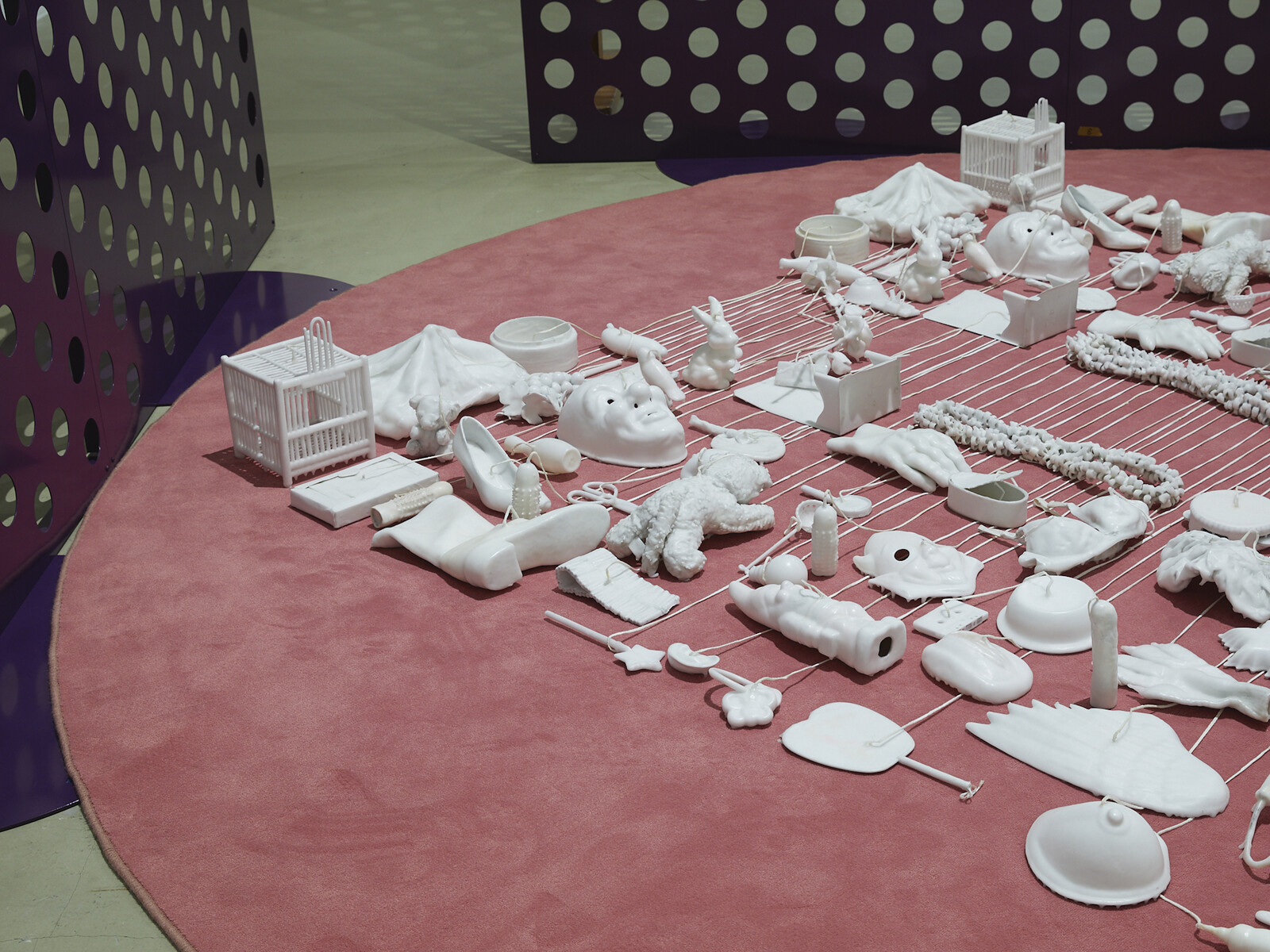

Buchanan describes the collection using bodily metaphors. We could think of the collection as a stomach, she told me at the opening, and the artworks like the gut flora, both healthy and unhealthy.4 The collection-as-body is conjured by Buchanan’s essay (“skin, bone, flesh”), her choice of keywords (legs and hands), and her own artistic interventions within the exhibition. These take the form of the booklet, typefaces, and the exhibition furniture Buchanan has made, to which she gives bodily attributes: “purple screens with fist-sized holes punctured into them, the tongue-colored supports, the ‘care’ green vitrines, the washy skin applied to the surface of the building with my brother Benjamin.”5 Buchanan’s round, pink pedestals (Tongues (Plinths), 2019) and liver-purple, perforated, room-dividing screens (When the sick rule the world, 2019) are especially prominent, and coax this crowded exhibition into further maximalism. The exhibition guide continues this thread of thinking the collection as a body: each of its entries, most of them researched and written by curator Kate McKenzie-Pollock, read like biographies, detailing each work’s acquisition and exhibition history. The result is equal parts dissatisfying and thrilling.

It is no small ask of an artist to reinstall a museum’s entire collection for its fiftieth anniversary. But it’s also a mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and power between Govett-Brewster and Buchanan, one which is likely to impact the institution’s collection priorities in the future. It’s notable that the museum’s most recent acquisition is a permanent wall painting, Kūreitanga II IV (2016), by Taranaki artist Wharehoka Smith (Taranaki Tuturu, Te Atiawa, Ngā Ruahine, Pākehā), which refers to the meaning of water to this place, the lore and practices of its people, and the shape of the Taranaki peninsula.

Audre Lorde, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 36.

Ruth Buchanan, The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong exhibition guide (New Plymouth, New Zealand: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2019), npg.

Ibid.

Interview with the author, December 7th, 2019.

Buchanan, The scene in which I find myself, npg.