As you walk up to Armada—through a courtyard ringed with industrial sheds and machine shops—placards appear to the right and left that read “adagio” (“drive slowly”), “non urtare” (“caution”), and again, “adagio.” Even if you aren’t the size of a truck, these signs have a way of making you proceed carefully, tentatively. As if moving through some large, lethargic organism. Armada is a former warehouse on the northern edge of Milan, converted into an artist-run space in 2013. The name brings to mind the fleet of Philip II, though there doesn’t seem to be any real connection. Except insofar as it’s managed by a crew of about 20 young people, with a range of artistic aspirations. What they all have in common is the experience of having studied at the Brera Academy under Alberto Garutti, a great figure in Italian public art whose presence can be felt here—the courtyard even contains a plaque with “Garutti” and a notice above it: “reserved, no parking.” His studio is close by.

Gerasimos Floratos’s solo show at Armada, “Soft Bone Journey,” is comprised of three large paintings in oil and acrylic, and three sculptures, each the size of a person, made of painted styrofoam. (All works are from 2017.) The colors are bold—canary yellow, acid green, pinkish orange. His approach to both mediums—simple lines, rapid gestures, rounded forms—has the feel of street art, a style that seems all too familiar, yet remains utterly foreign. The subjects cannot be fully made out: at first glance they resemble digestive tracts, limbs, current collectors, crumpled billboards, tangled topographies. The titles, too, hint at things without saying them straight out: Internal Trash Dog, Soft Bone Slumper, Untitled (the paintings); International Soft Body, Town Square Alignment, Reverse Hackie Roleplay (the sculptures). Although the style is more abstract than figurative, they all vaguely point to the human sphere, something having to do with us. Not busts, but rather portraits, as Armada’s Georgia Stellin notes, “from the navel down.” We’re in the realm of autobiography.

His last name is Greek, as is his first, which means “old age, elder.” Yet Gerasimos Floratos looks even younger than his thirty-one years. When I meet up with him at Armada, a few hours before the opening of the show, he has peroxide blond hair, a hoodie two sizes too large, and a notepad full of drawings tucked under his arm. His manner is polite and cheerful, putting emphasis on the importance of art to him. He’s also curating exhibitions for several galleries at the moment. Fully in the swing of things. Floratos was born in Manhattan, but his roots are grittier: his father, who runs a deli in Times Square, moved to the US in the 1970s from Cephalonia—the sculptures on view here, which can be easily picked up and transported, were made at his paternal grandmother’s house on the Greek island. In New York, Floratos likes to get around by taxi—a symbol of the city and part of its mythos, as is Times Square, for that matter. “The images that flash by outside blend together in my mind and then on the canvas,” he says, and it’s a motif that turns up over and over in his work. At Armada, for instance, we find Reverse Hackie Roleplay, a small sculpture placed next to pieces of scrap from the courtyard. If you look closely, you can make out a small yellow vehicle and a raised thumb, also yellow. “It’s a cab hailing itself.”

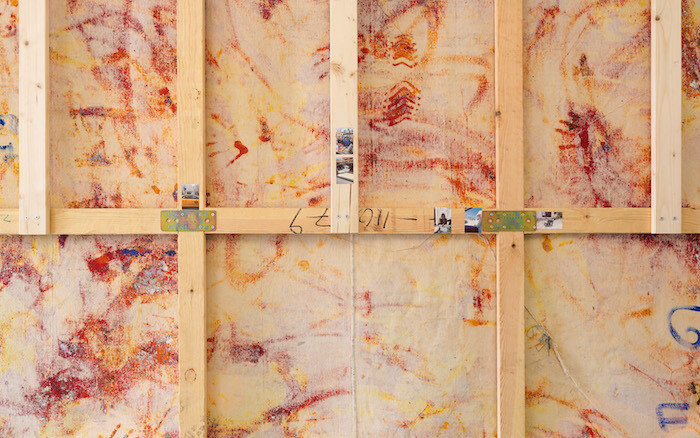

The photo used to publicize the show was also taken from inside a car: the rearview mirror shows a small white dog in the back seat, its muzzle all ruffled by the wind. “That’s my aunt’s dog,” he tells me, leading me towards the biggest painting, TBC, hung in mid-air rather than on the wall. He shows me not the front (where we seem to see two big, droopy rabbit ears against a carrot-colored background) but the back: “And that’s my aunt,” he adds, pointing to the photo of a woman winking over her sunglasses. Next to it are more snapshots: “Here’s my dad at the deli… my uncle crawling around like a cat… another white dog in a taxi…” These photos lined up on the stretchers seem like the artist’s attempt to remind himself where he comes from. While on the other side, the canvas holds the ungovernable figures of his many selves, which refuse to obey form, as Floratos says: with “broken hips and floppy bones,” and yet in transit. He says goodbye with a handshake followed by a fistbump and a whole dap routine that takes several attempts to memorize. He has an appointment in town and tries calling a taxi, since they can’t be flagged down in Milan. Somebody tells him there’s a taxi strike. He claps in excitement, amused: “No way!”