As a real chilanga, born and raised in Mexico City, Paloma Contreras Lomas is familiar with the ultra-centralized bent in Mexican culture: how the images and discourse produced in the capital solidify into countrywide narratives through their reproduction in the media and popular culture. Her awareness of her own position as a white, middle-class urbanite, an artist who inserts herself into sites of Mexican rurality, is apparent in her critical approach to such typical representations as the rocky Durango mountains and brown-faced white men acting tough (as seen in so many Westerns); the Mexican state’s dispossession of impoverished rural areas on the pretext of “rescuing” them; the concomitant vilification/romanticization of drug-dealing men through the deep yellow filter beloved of Netflix cinematographers. These stereotypes come back to questions of displacement: the agency to tell stories rarely belongs to those who live them, as the stories of Mexico’s rural populations tend to be told by those who exist in geographically proximate but profoundly different realities.

Contreras Lomas’s work explores the liminal space that exists between real landscapes and the fantasies projected upon them. In her portrayals, that space becomes the site of what might be called an Extractivist Gothic. In the video Más allá Mexicano (all works 2020), that which is absent dominates the sunny, overexposed beige of Sierra Hermosa, a downtrodden mining town in Zacatecas. Hills emptied of their minerals, the hollow shell of a hacienda, and deserted streets betray a history of extractivism. The town is haunted, as the voiceover explains, not only by the revolutionary past, or the young men who have left for the supposedly greener pastures of bigger cities or across the border, but also by Contreras Lomas’s own, urban-minded understanding of the place. Her reading, it’s implied, is obstinately inauthentic, inevitably uncomfortable, and possibly guilty of its own form of extraction.

The words, spoken by a man but using feminine grammatical forms, are filled with the artist’s own erotic yearning. He voices the desires that Contreras Lomas whipped up while dating a norteño: how she imagined him as rougher, sturdier, how she wished he would fuck her with his rifle in an abandoned house, her delight that he was constitutively not from el centro. Such fantasies populate her video, laying bare the way places may seem to be inhabited by archetypes. The men shown here are norteños, narcos, migrants, mining engineers, or warped versions of them: they hold furry neon guns and wear fringed red-and-blue head-to-toe outfits; the engineer roams the white-hot mine wearing a black ski mask. Women, children, and the elderly, so often excised from narratives of masculine bravado, appear here, reciprocally haunting and haunted by their circumstances, keeping the town barely alive by performing miracles out of remittances. Contreras Lomas walks a fine line between questioning her own role in the profitability of oversimplified stereotypes and perpetuating them. Her work is not necessarily ambivalent, but it confronts the uncertainties inherent in translating others’ lives into art: who can speak on what subject? in which terms? in what tone?

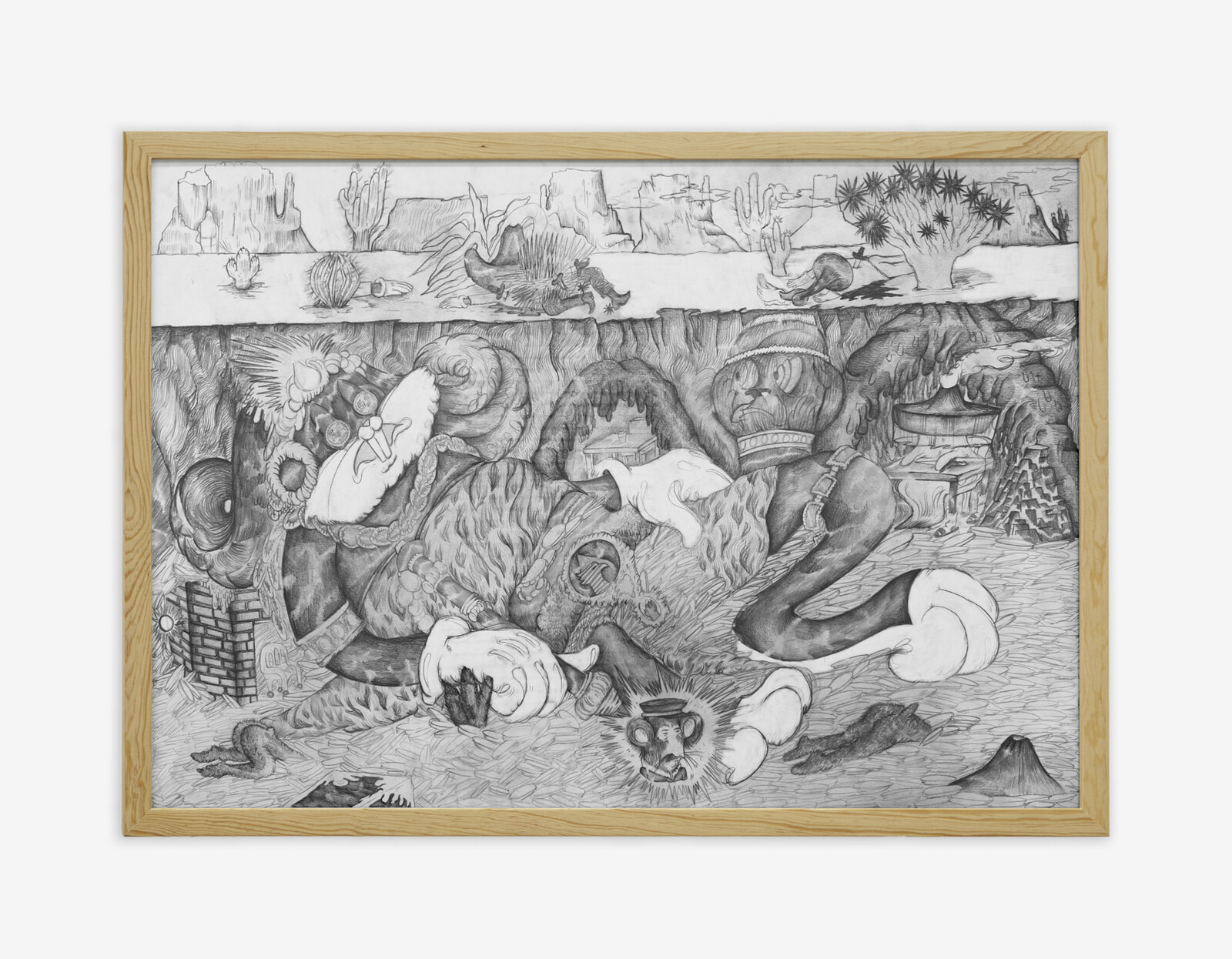

A series of soft sculptures reimagine the desert’s cast of characters through the muddling lens of displaced representation. Quentin Saguarantino, un thriller is a fluffy, piñata-colored saguaro cactus, brandishing a fleshy gun and an oversized cigarette in Mickey Mouse-style gloves. A giant, stuffed Bugs Bunny in ¿Estamos, Kimosabe? is overtaken by the desert brush, only his legs and arms visible under a massive sombrero as he naps against a gallery wall, all the while keeping a firm grip on his gun. Both Cimarrón and Sergio Leone asesina a la Conasupo are hat-sculptures in the shape of hills and cacti, which visitors can try on, thus literally assuming a physical history of atrocity and dispossession. As she interrogates the impact of mass media and the corporate interests behind predatory operations like the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, Conteras Lomas represents the Mexican landscape as a house haunted by the victims of capitalism. This, she suggests, is the reality in which we—chilangas and norteños, artists and their subjects—are all trapped.