Much of the material labor that drives the western world—rubbish collection, farming land, fulfilling Amazon Prime orders—is invisible. Or, in its most exploitative forms, has been made invisible, disappeared for consumers’ benefit in fortress-like fulfillment centers or unsafe garment factories in the Global South. Yet in Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir’s exhibition, manual labor is highlighted, abstracted, and aestheticized.

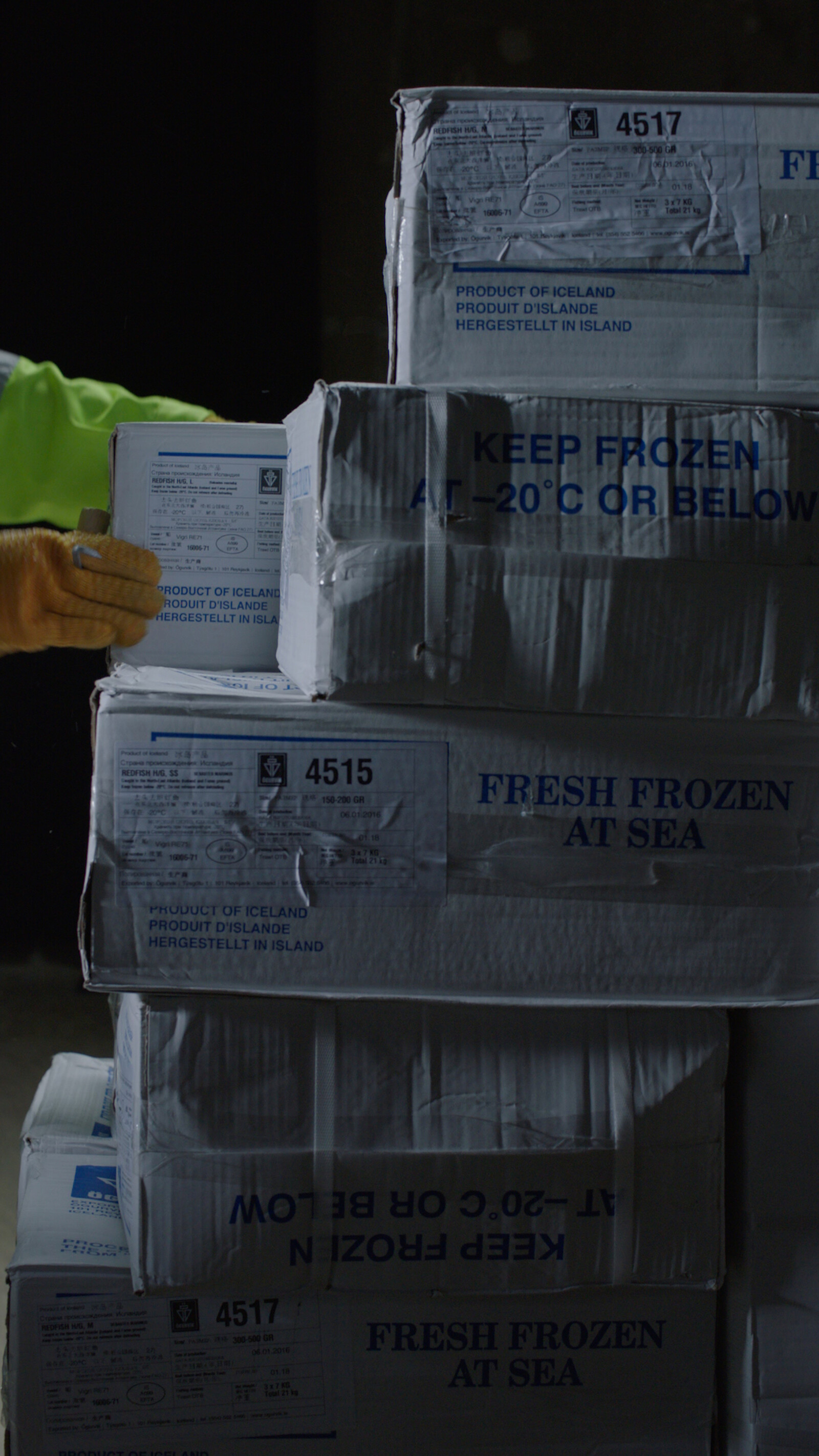

In an elongated, darkened exhibition hall in the Reykjavik Art Museum’s harborside Hafnarhus location, more than 5,000 white cardboard boxes emblazoned in blue with the words “KEEP FROZEN AT -20 OR BELOW; FRESH FROZEN AT SEA” are stacked floor to ceiling; some jut out at regular intervals like decorative building bricks. Lining the walls almost entirely, they envelop the space. These particular boxes are empty, but normally each would contain 25 kilos of frozen fish, to be transported by freezer trawler to Rekyjavik’s harbor, where they are speedily unloaded by teams of dockworkers, entering the economy as one of Iceland’s primary natural resources (tourism only recently surpassed fish as its primary export).

We see several of these workers in the three-channel video Labor Move (2016), installed on large, vertically oriented screens suspended at even intervals along the hall’s long interior wall. The on-screen protagonists are burly men in helmets, coveralls, and gloves. Strategically lit in a dark space, they toss the boxes (which are visually the same as those in the space), stack them on palettes, and roll them on forklifts. The boxes in the video are filled, and land with resounding thuds. The camera follows moments of graceful movement, but also captures glimpses of brute force and physical fatigue. Repeating closeups of boxes and men jump from screen to screen in succession. The sounds of impact—but also singsong directives like “swing” coming from the men as they push, pull, toss, and roll—are manipulated like a DJ might scratch a track: clacks and hums reverb and repeat percussively.

This video work is the latest in a series of pieces based on a body of artistic research that Guðnadóttir, whose academic background includes a degree in anthropology, began about a decade ago. Then, curious as to what the new cultural spaces, luxury housing, and boutiques in her home city’s harbor were “replacing,” she discovered a largely hidden aspect of the fishing industry: teams of workers regularly emptying fishing trawlers on a central dock (in general, 20,000 boxes in 48 hours in a working environment of -22 degrees Fahrenheit: “keep frozen” indeed). Her contact with the workers, backed by extensive research on Icelandic fishing policy under Danish colonial rule and thereafter,1 became the feature-length documentary Keep Frozen (2016), which is also screened in the museum at regular intervals. In 2016, some of the same dockworkers later performed their work under Guðnadóttir’s direction in Leipzig’s Kunstkraftwerk—moving a fishing trawler’s worth of boxes in 48 hours in a large performance space for the purposes of culture, not commerce. Labor Move’s source footage comes from this event.

While this latest work is the most abstract remix of Guðnadóttir’s exploration of Icelandic dockwork (and, indirectly, of Iceland’s place in the global economy) it also most dramatically reveals the workers’ unrehearsed choreography. The artist avoids either inciting outrage or merely exposing exploitation; rather, her work lays bare the beauty or value in manual labor, and grants it the dignity it once widely claimed, perhaps even “unalienating” it in the Marxian sense by establishing exchange value in another field.

The exhibition is mesmerizing, but also sobering, despite or perhaps because of its straightforward, reduced presentation of only three works. Curated by Birta Guðjónsdóttir, “WERK – Labor Move” is a reminder of how foreign the sight of manual labor has become in the Global North. Once working from a building where the Olafur Eliasson co-designed Harpa concert hall stands today, dockworkers now unload fish on a quay further from the city center. And until 2000, the very building where this exhibition is displayed—one of Reykjavik Art Museum’s three venues—was a harbor warehouse.

It’s also a clear expression of how we all exist within webs of production. At the entrance to the exhibition space, amidst books in the museum shop, is the easily overlooked Labor Love (2021), a flat-screen video showing museum employees assembling the 5,000-odd boxes in this show, methodically folding them as if on an industrial assembly line. Guðnadóttir has stated that artists and dockworkers have much in common: culture work, too, can be tedious, unseen, unrecognized, and material.2 In Keep Frozen, a dockworker muses on how his work is like a dance, but it’s also “just moving shit from one place to another.” Here it’s impossible to forget that we all move invisible or visible shit—money, words, ideas, rocks, packages, frozen fish—in different ways. How much of this we recognize, or accept, is up to us.

Iceland gained independence from Denmark in 1944; in the postwar era the country received aid through the US Marshall Plan. US military maintained a presence here until 2006.

The artist mentions in an interview that one of the dockworkers later joined the “creative class.” She has also staged performances in Reykjavik in which the roles of artist and dockworker are reversed. See Hulda Rós Guðnadóttir (ed.), Keep Frozen: Art-practice-as-research (The Artist’s View) (New York: De-Construkt, 2015).