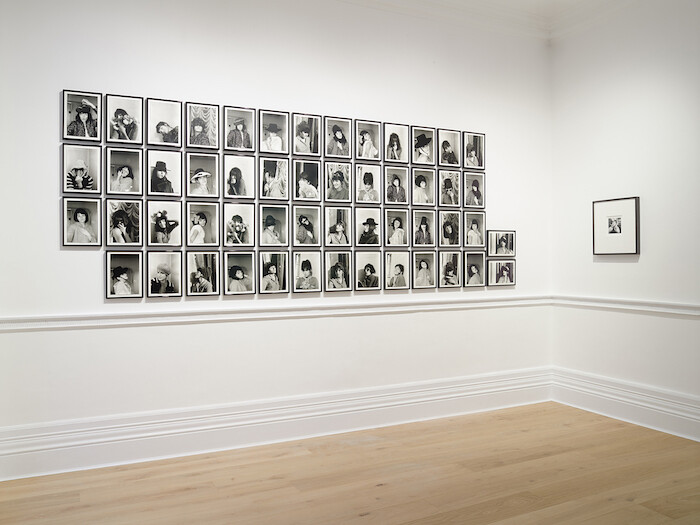

I almost walk past the entrance to “Women Look at Women,” the inaugural exhibition at Richard Saltoun’s new space on London’s New Bond Street, delayed and disorientated by the glossy rows of designer shops and galleries that surround it. Catherine—a friend on a break from the picket line where she, like many UK university lecturers, is fighting to keep her pension rights—is already there, taking succor from women’s images of themselves and each other. “I was just looking at this,” she says, pointing to Marie Yates’s photographic installation The Missing Woman (1982–84). Catherine’s gesture encompasses a wall of irregularly spaced photomontages: a mixture of grainy, hand-tinted images, polaroids, photocopies, and text rendered in Courier typeface and neat handwriting. One image—a color photograph of a telephone receiver and a telegram overlaying that of a roadside in blurred black and white—is accompanied by the line “Somewhere there is a point of certainty.” It holds out an unattainable promise of clarity in the game of decipherment and elusive autobiographical disclosure which Yates’s images put into play.

The Missing Woman speaks of a time—broadly stretching from the 1960s to the mid-1980s—when women’s images were troubled and interrogated by a newly confident feminist articulation, finding its voice where activism and art converged and clashed. That Yates’s installation featured in the 1983 exhibition “Beyond the Purloined Image,” staged at London’s Riverside Studios and curated by artist and theorist Mary Kelly, grounds it in the particularities of the psychoanalytic and semiotic discourses which once sensitized feminists to the potency of their own image within patriarchy. “Women Look at Women” is a historical show, principally focusing on photography, that invites questions about the situations out of which these works emerged, the extent to which feminism was relevant to their protagonists, and what was at stake for women artists back then. Did the women’s movement provide for them a point of collision? Was it background noise or a movement in which they were actively engaged? Did it come too late? Or did they feel that its energy was already spent when these images were made? That these questions are left unanswered in “Women Look at Women” provides both the exhibition’s strength and its frustrations.

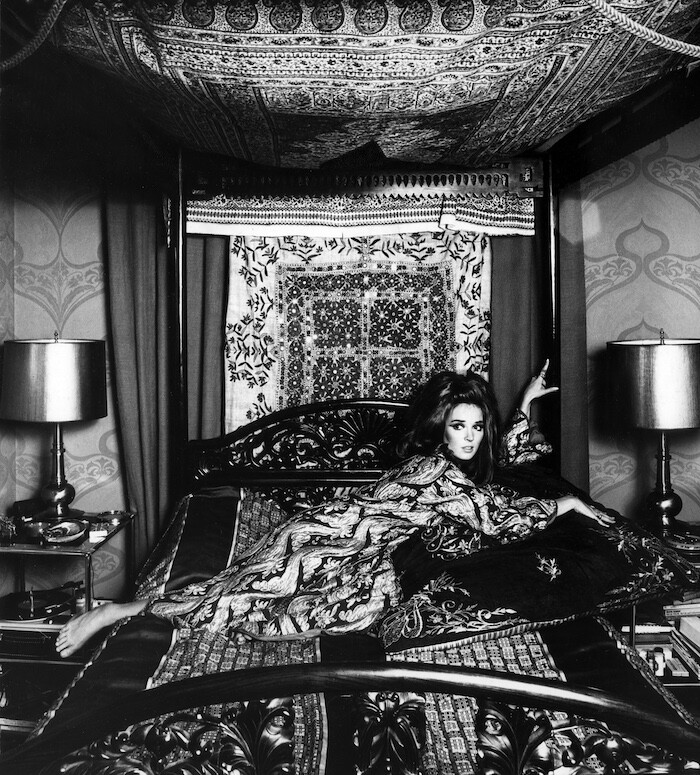

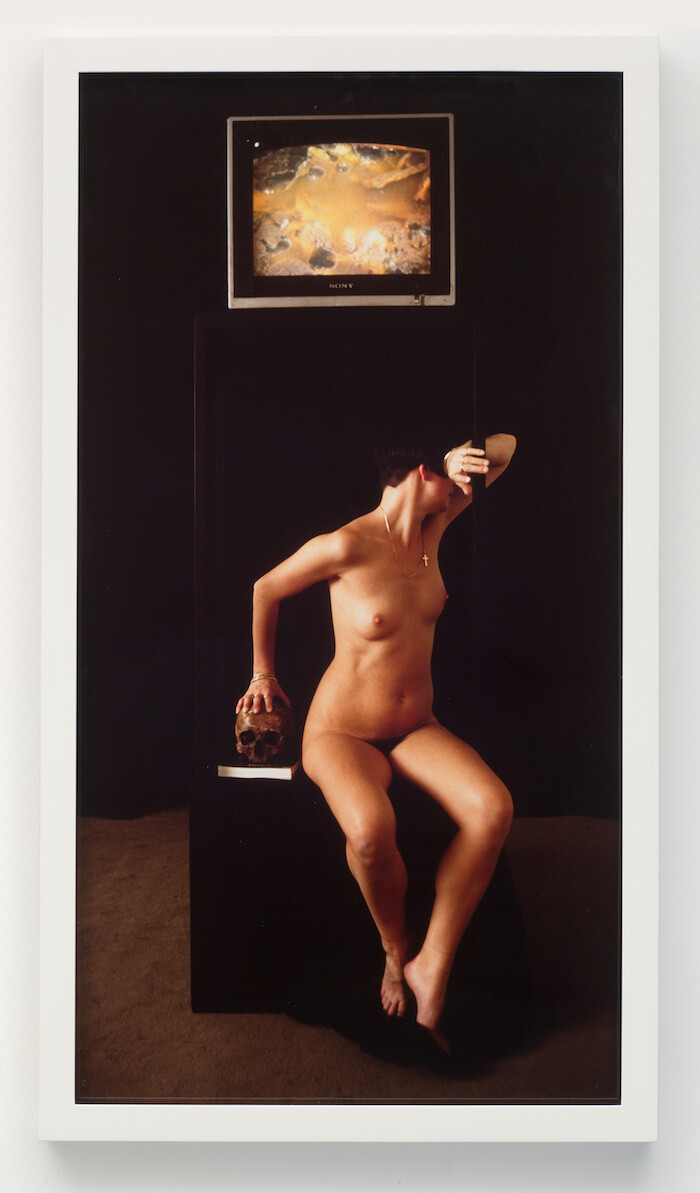

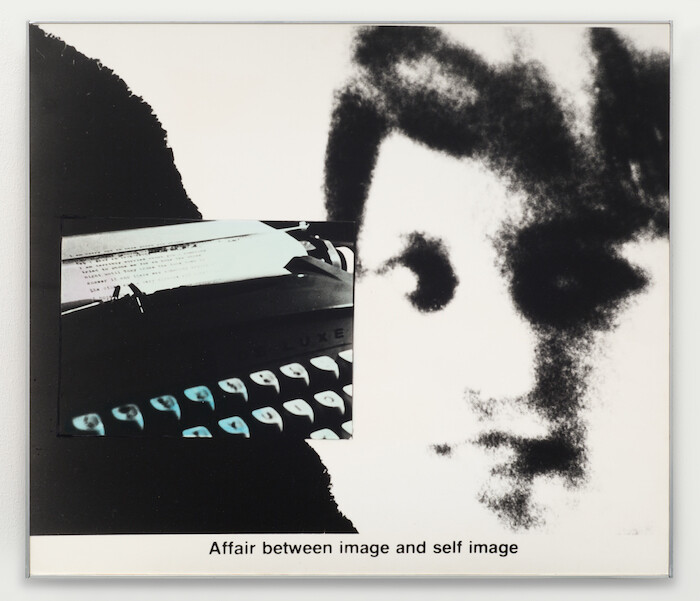

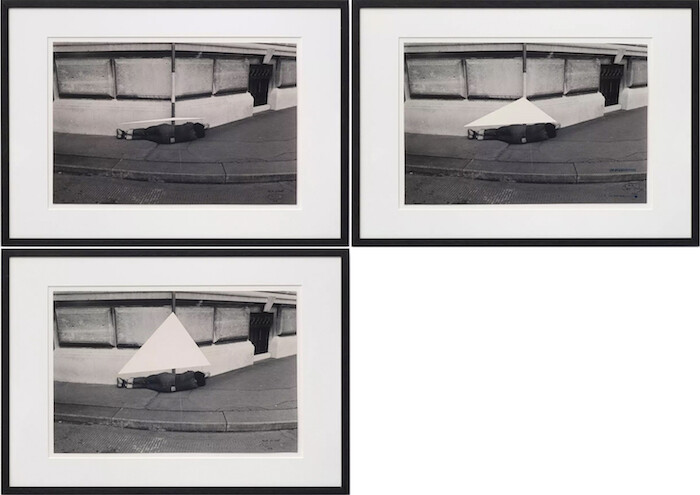

The images range from late 1960s Germany—with a compelling series of photographs by Renate Bertlmann (Verwandlungen (Transformations), 1969/2013), in which she tentatively tries out personas for the camera—and ends in 1986 with Ruin (1986), Helen Chadwick’s staged Cibachrome prints of herself, refusing the camera’s gaze as she turns from the lens. It is not clear whether this roughly twenty-year span indicates an engagement with female portrayal seen as particular to the period, or whether the exhibition’s purpose is to advocate female artists who have addressed self-image, setting iconic figures such as Francesca Woodman, VALIE EXPORT, and Eleanor Antin against lesser-known examples such as Bertlmann or Annegret Soltau. The psychoanalytic orientations of the British context are most keenly reflected in the work of Yates and her counterparts Jo Spence and Helen Chadwick, where the self is rendered as fragment or fugitive—in the textured magnification of Spence’s clasped hands (Body Parts, 1978), for example, or the faint impression of Chadwick’s body, little more than a photographic stain upon the plywood surface of the three boxes, as enigmatic as sarcophagi, in the first rooms of the gallery (Ego Geometria Sum I: Incubator – birth, 1982–83). I am also reminded of the wry humor that can accompany confrontation with self-image. Rose Finn-Kelcey converses with herself on a park bench (Conversation Piece (Divided Self) 1, 1974), while the disembodied fingers of Alexis Hunter’s secretary (in her 1978 photo series “Secretary Sees the World”) toy with a miniature globe—a world out of reach beyond her repetitive labor at the typewriter keys.

But this is just to list some of the exhibition’s treasures, which Catherine and I fall gratefully and greedily upon. Does it matter that the extensive contextual detail that we have come to expect about artists’ work, exemplified in such recent exhibitions as the London’s Photographers Gallery 2016 show “Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s,” is not forthcoming? It could be argued that a lack of historical context liberates the images to speak on their own terms to a fresh generation of young artists, whether they see themselves as feminist—or indeed gendered—at all.

For Catherine and I, “Women Look at Women” begins a feminist tour of West End galleries: something that would have been unprecedented even five years ago. It is thrilling to see Lorna Simpson’s collages and sculptures, which incorporate copies of Ebony magazine, command the slick space at Hauser & Wirth, and to finally have the opportunity to see Faith Ringgold’s glowing, witty quilts at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. Greater recognition for women artists is predicated on them taking up such spaces. But something of the disorientation with which I first entered Richard Saltoun Gallery remains. “It’s a question,” Catherine says later, “of what’s shifting and what’s not.” I locate my unease in how the advocacy of the art market has begun to play a new role in the advocacy of feminist art, in a shift away from the publicly funded contexts that once provided its axis. “Women Look at Women” provides a valuable introduction to the dynamic field of engagement of which these women artists were part. The question for current feminist scholars and artists is how to negotiate the new exchange values their bodies now hold.