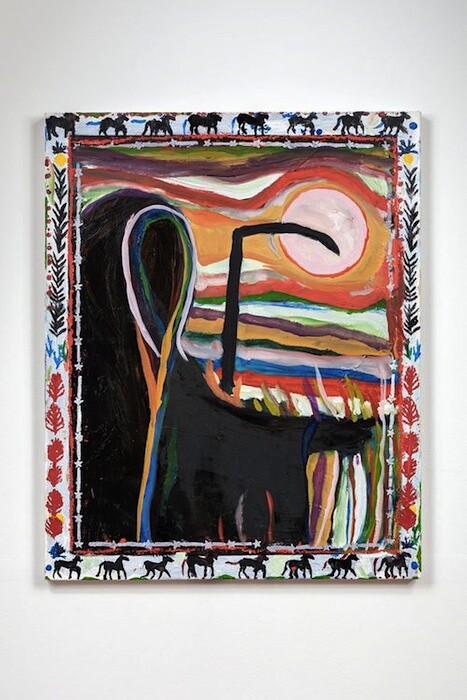

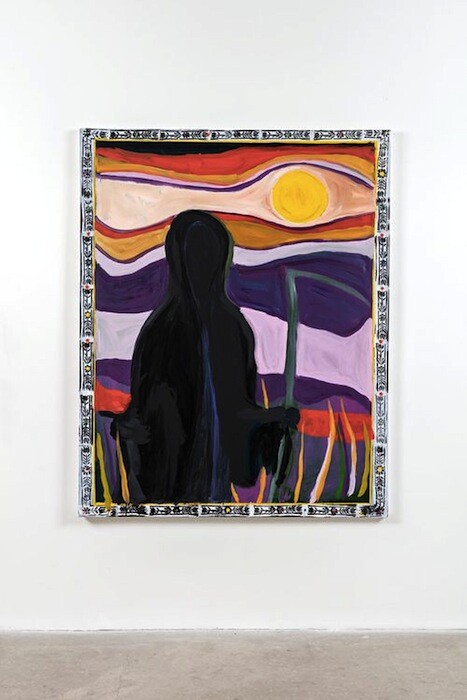

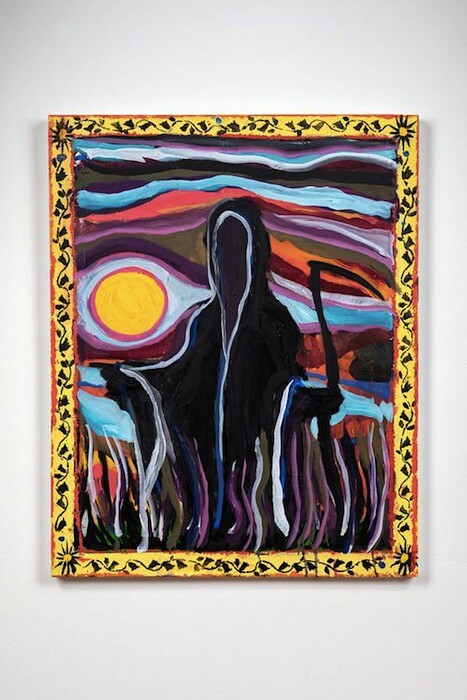

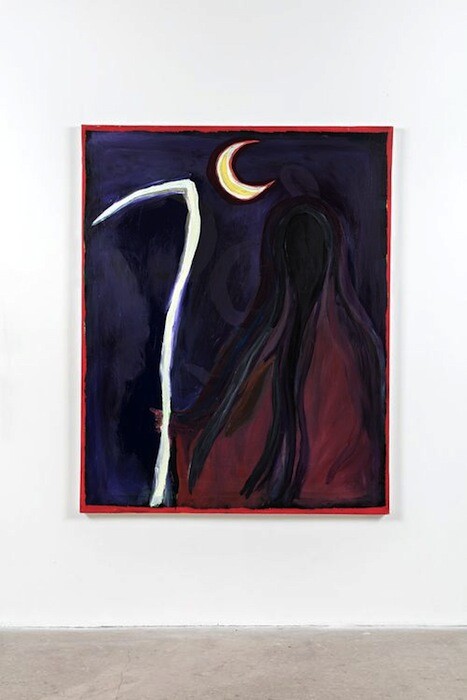

The visitor to Josh Smith’s show at STANDARD (OSLO) is faced with 11 Grim Reapers painted in oil on canvas, all of them equipped with the customary black robe and scythe. Smith’s angels of death are not solitary, otherworldly figures, but a motley crew rendered in a seemingly slapdash manner, like the paintings you come across in flea-markets and thrift shops. The kitschy feel of these paintings recalls one reviewer’s description of Smith’s recent work as “Edvard-Munch-goes-to-the-Bahamas,”1 but here the cardboard sunsets are relocated to the Northern Hemisphere. The most Munch-like of these works—including Time for Yourself and Easy on the Being (all works 2017)—are grouped together, but the majority are presented in relative isolation on the gallery’s white walls.

Gone are the artist’s “signature paintings” with the words “Josh Smith” scrawled all over them. Has the artist forgotten his former conceptual strictness? The wilful amateurism here anchors the paintings in the world of post-expressionistic outsider art, but Smith’s eccentricities seem more focused than most. He played with our expectations when using his own name as a motive and template—emptying the canvas of painterly authenticity and authority. In these paintings he achieves something similar with the presentation of death. The result is an updated version of the memento mori, which doesn’t restrict itself to the motive itself, but interrogates how we expect death to be addressed in “serious” art. What looks initially like carelessness is, in fact, quite the opposite.

Smith’s main inspiration is the chess game between the knight (played by Max von Sydow) and the reaper (Bengt Ekerot) in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). The Norwegian chess-player Magnus Carlsen, and his endless virtuosity, provides a less obvious source. In both cases, death is masked by a story about the struggle to excel in living, to be remarkable. The image of the knight tricking death is human in its refusal to accept mortality. This epic existentialism is close to stereotypically Nordic, and can be detected in the influence of Munch, but the show also brings to my mind other art historical references. These range from the blackened piece of coal that inspires Bjarne Melgaard’s architectural proposal for A House To Die In (2011– ) to tasteless parodies like Damien Hirst’s In the Name of God (2007), or Thomas Hirschhorn’s more aggressive Crystal of Resistance (2011), which shows mutilated bodies on touchscreens. The comparisons raise the questions of whether the representation of death is more powerful in banality, like Smith’s, or in the elaborate stagings of Hirst, Hirschorn, or Melgaard.

Smith has elected to portray death in the most clichéd manner. This is further underlined by the way he mimes the swirling, layered horizons in Munch’s paintings—an easy aesthetic gesture which in this context brings forth a crude finish that strengthens the critical project. By reciting this hackneyed figure and shamelessly parodying the gloomy strokes of Munchean melancholy, the army of Grim Reapers breaks through platitude. Stripped of the stylistic or narrative features which make it possible to fetishize death, he holds our gaze. Repetition and non-virtuosity releases death from stage directions and smart theatricalities.

Along the edges of these paintings are decorative borders depicting animals and flowers (as in the suns and birds that fringe The Cold Wind is Coming). Seemingly foreign to the bleak subject matter, they counterpoint the self-importance with something ordinary, even silly. The cuteness and the outsider style pull in the same direction as the repetition: towards the anonymity and triviality of death, rather than the grandeur of epic storytelling. Smith allies himself with the banality of the end. No fetish, no epic tale, no sublime house for dying. These works create a space for thinking about death that surpasses most of Smith’s peers’ attempts. These paintings are also funny. The aesthetics of non-originality deprives death of his grandeur.

David Rimanelli, “Josh Smith/Luhring Augustine,” Artforum, Vol. 52, No. 4, December 2013.