The four works assembled in Michael Snow’s “Closed Circuit” are not among the artist’s best-known. Visitors expecting the long mechanical arm of De La (1969–72) or the recto-verso double projection of Two Sides to Every Story (1974) will be disappointed. For all the bombast associated with the Guggenheim Bilbao, this is a small, quiet show. Yet its unassuming stature belies a conceptual clarity, as judicious selection creates a sharply honed portrait of an artist long devoted to exploring vision—embodied vision, machine vision, and the nexus between them. It is a portrait in which film, the medium for which Snow is best known, takes a backseat to questions of interactivity, real time, and surveillance.

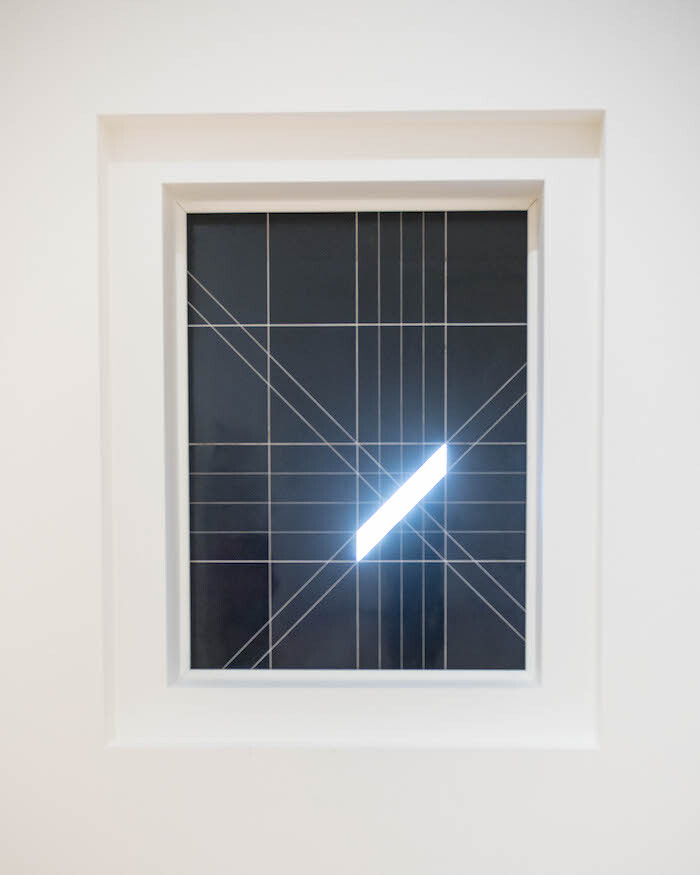

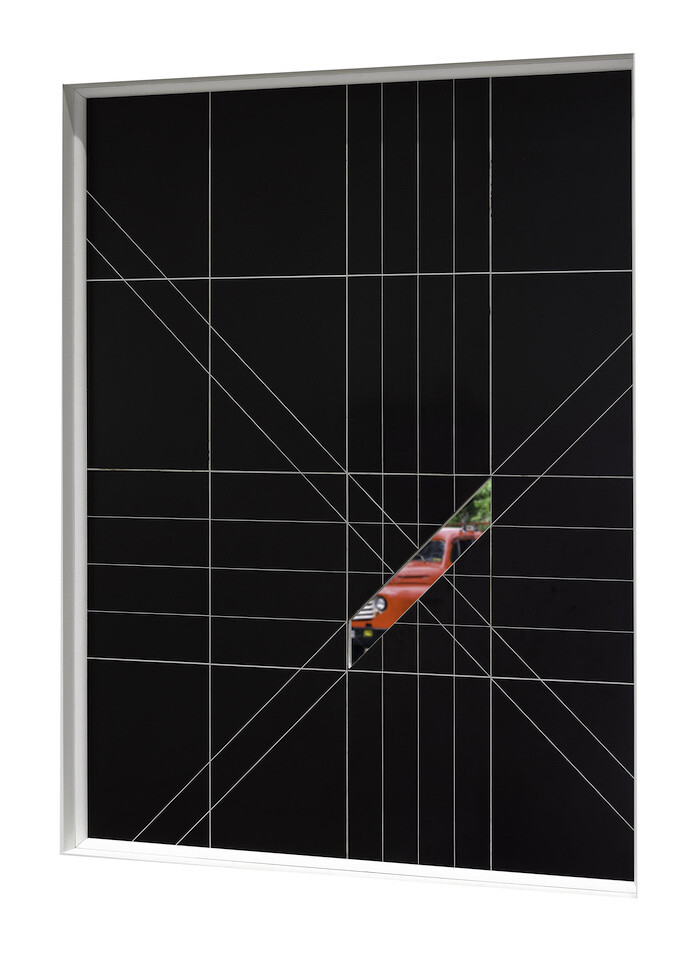

Snow’s concern with perception is signaled immediately by the titles of Sight (1968) and Observer (1974). Positioned at the entrance to “Closed Circuit,” Sight is a black window covering made of aluminum and plastic, mostly blocking the view of the Nervión river outside, save for a diagonal rhomboid aperture excised from its geometrical patterning. Faced with the resulting tension between interior and exterior, surface and depth—themes that recur elsewhere in the exhibition—binocular vision falters, leading to a phenomenological reduction whereby I see myself seeing.

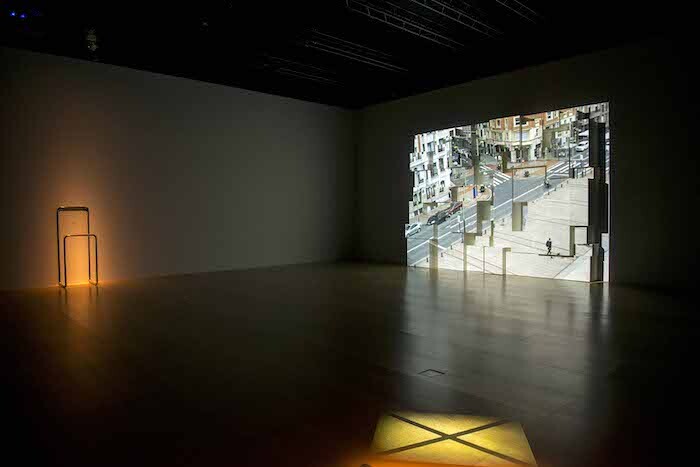

A similar self-consciousness emerges from the closed-circuit projection Observer. Standing on an “X” marked on the floor, I am captured from above by a camera, with the resulting image projected onto a second “X” immediately in front of me, also on the floor. I am caught in the crosshairs of the apparatus. If Sight returns me to the physiology of seeing, Observer complicates the relationship between body and vision further to include technological mediation, using CCTV to stage the jarring experience of seeing myself being seen from a position I will never be able to occupy. Like contemporaneous closed-circuit works by Bruce Nauman, Dan Graham, or Peter Campus, Observer offers a lesson even more relevant in the age of social networks than it was in the early 1970s: apprehending oneself as a mediatized object has its pleasures, but it raises the unsettling specters of surveillance, control, and even violence.

Site (1969/2016) does not use moving image. But it is clearly related to Snow’s acclaimed film Wavelength (1967), in which a static camera slowly zooms in, over the course of 45 minutes, on the far wall of a studio loft. In Site, a U-shaped stainless steel structure functions as both frame and barrier, drawing my attention to a small placard on the wall yet barring me from closeness to it. In soliciting this bodily conduct, Snow warns us to not believe the hype: movement is not freedom. As I lean forward, conscious of the restricted access, a short, typewritten text becomes legible: “I considered using, here, an image of the sea, of waves, but I finally decided to use this. Michael Snow ’69.” The artist’s trademark dry humor creeps in: he is referencing the postcard of the sea that brings Wavelength’s inexorable zoom to rest.

Along with the slide piece Slidelength (1969–71), currently on view at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Site might be understood as a cross-medium remake of Snow’s 1967 film, using text to replace image and the viewer’s leaning body to stand in for the camera’s zoom. It is a work of cinema by other means, part of the project to disarticulate “cinema” from “film” that would preoccupy artists such as Tony Conrad and Anthony McCall in the 1970s. Yet it also toys with the game of fame. Minimalism may have seen a vanishing of the artist’s hand behind the impersonality of industrial fabrication, but in no sense did the death of subjective expressivity entail a rejection of signature more broadly conceived. Here, Snow pokes fun at the notion that artists are expected to ceaselessly repeat their most celebrated interventions, at once refusing and acquiescing to the demand.

The Corner of Braque and Picasso Streets (2009) dominates the space. A live video feed from just outside the museum pipes in all the mundanity of daily life. Tourists snap photos of Frank Gehry’s out-of-frame architectural spectacle, the dogs of Bilbao take their morning walks, and delivery vans pass by. Instead of a standard screen, the image is projected onto a Tetris-like array of disused museum plinths, creating sculptural seams that fracture the integrity of the picture plane. There are, of course, no streets named for Braque and Picasso in Bilbao. The title names representation, not reality: the invocation of cubism speaks to Snow’s incorporation of quotidian materials into an aesthetics of spatio-temporal refraction. True to the interests Snow has pursued since the 1960s, the work dismantles illusionism by reversing the usual operation of flatness and depth in moving-image projection: instead of a flat screen enabling perceived depth in the image, here the sculptural relief of the screen reveals the image as a flat skin of light. The CCTV feed—the image that would seem to be most real, most proximate to the profilmic, so tied to securitization and the management of populations—here becomes plastic and malleable. But of course, as Snow knows, it always was.