Here are some of the phrases the visitor will encounter at “The Weight of Words,” a group show featuring eighteen living artists and writers working across sculpture and poetry: “WHAT IF NOT EVERY WORD IN YOUR SENTENCE;” “Traducing Ruddle;” “as you wlak [sic] the distance changes; ” “stilllife;” “EFEND DIGNITY COPY AND ORIGINAL.” Out of context, these formulations sound more like material gathered by a lexicographer or anthropologist than lines composed by a poet. Yet the works that feature them are poetic in the best of senses: distilled and suggestive, affecting in ways I can’t quite explain and yet will remember.

The curators, Clare O’Dowd and Nick Thurston, argue that the works on display represent the meeting of two traditions that have been artificially separated and codified. Sculpture and poetry are taught and interpreted as distinct disciplines, when they are in fact intimately connected by purpose and technique. Several of the artists here point to literature in their work: Joo Yeon Park’s kit-like engraved aluminum is a fragment of potentially infinite architecture such as that imagined in Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Library of Babel” (1941); a commissioned text by poet Anthony (Vahni) Capildeo, swimming amongst fish in a blue vinyl mural on the gallery’s front wall, quotes Simone Weil; Doris Salcedo’s monumental Untitled (2008), made of used wooden furniture and concrete, references Paul Celan. But strikingly, as a whole the show moves beyond the more familiar processes of disciplinary exchange often grouped under the fashionable umbrella of ekphrasis.

The gallery doors are papered with “notional newspapers” made by Mark Manders, their nonsense news illustrated by images of miscellaneous debris, recalling Man Ray’s photograph Dust Breeding (1920), taken in Duchamp’s studio. Manders intends the exhaustive project to use every word in the English language, in what could be an ironic riff on Ezra Pound’s definition of poetry as “news that stays news.” The nearby Standing Heech (2007) by Parviz Tanavoli has a contrasting impulse: to make something from nothing. “Heech” means “nothing” in Farsi, and the pert, avian-green sculpture resembles the Persian letters which make up the word. It’s a simple gesture, the liveliness of the form working against the signifier out of which it has grown, and the dynamic is beautifully caught. Stepping back, I almost fell into Untitled (Cornucopia) (2019) by Leslie Hewitt, propped against the wall. The photograph is a still-life arrangement of books, acting as a plinth for a block of wood. Like the works around it, the restrained, precise piece invites an uncertain combination of looking and reading, not unlike the halting process of learning a language.

The quiet is punctuated by the clatter of a black motion flipboard, like that used to convey information in a port or train station. Shilpa Gupta’s commanding Words Come From Ears (2018) gives the airy central space an atmosphere of busy transit. I lingered to read the delight on the faces of two visitors as they watched the physical arrival and departure of each new line of Gupta’s disjunctive, slippery text about desire and shame. Next to them, Syrian-born Issam Kourbaj’s fleet of tiny boats sails exposed along the gallery floor. Kourbaj has added a boat—made of bicycle mudguards and carrying burnt matches—every month since the beginning of the Syrian civil war and subsequent refugee crisis. To reflect the monthly additions, the title, Dark Water, Burning World: 148 Moons and Counting… (2016–ongoing), has been crossed out and changed twice since the show opened.

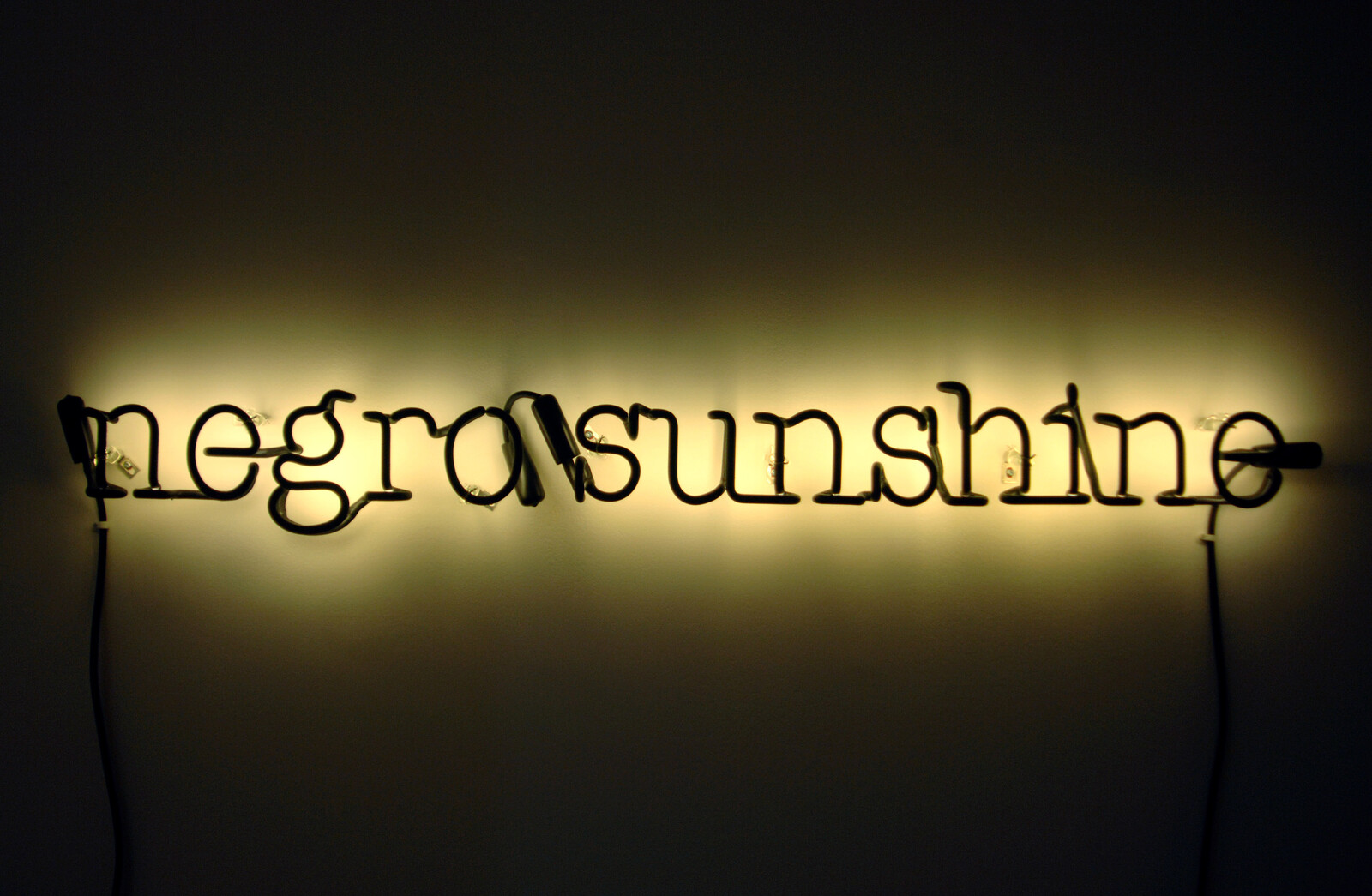

There is a playful yet insistent resistance throughout the show to the commonplace assumption that language is a weightless, neutral resource. Kourbaj’s strikethrough is a visual reminder of the persistent material trace of apparently forgotten or discarded words. Glenn Ligon’s Warm Broad Glow (2005) also involves a compelling act of partial erasure. Ligon took a racist passage from a novella by Gertrude Stein, hero of the avant-garde, and rendered her phrase “negro sunshine” as a neon. He painted the neon’s front black, eclipsing the white glow and “taking back the very idea of Black joy.” In a note, I described this work as a highlight of the exhibition, only to realise that is it precisely this species of metaphor—which unconsciously associates lightness with goodness—to which the work invites the viewer to pay attention.

Ligon’s neon is joined by Slav and Tatars’s Szpagat (2017), a polished metal tongue doing the splits on a wooden plinth, and Say Parsley (2004–23) by Caroline Bergvall with Ciarán Ó Meachair, in which a voice speaks Irish and English words projected on the wall. The title references a 1937 massacre of Creole Haitians on the border of the Dominican Republic, because they failed to pronounce “perejil” (parsley) in the accepted Spanish manner. It’s a typically clever curatorial decision to place these works about borders, coercion, and violence at a point where the visitor meets a physical dead end, one foreshadowed by the earlier incorporation of a shuttered gallery door into Bhanu Kapil’s Twelve Questions (2001/23). You have no choice but to turn around and follow your footsteps. I became hyper-aware, walking back through the exhibition, of the physical presence of text: on a glass screen, under my thumb, a message; in black vinyl on the wall, public and previously unnoticed, “CCTV is operational in this area.” Words are always made out of something, and in the works on display here, the medium makes all the difference.