I was wrong. I walked into “Defiant Muses: Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France (1970s-1980s)” thinking the exhibition would be about “her” and “them,” and the past, only to realize that it is about “me” and “us,” right now. About sexism, silencing, inequality, discrimination, patriarchal oppression, rebellion, and about changing narrative paradigms. The show looks beyond Seyrig’s singular persona as “iconic” actress, to reconstruct, instead, a far fuller picture of her life and work as activist, feminist, director, and collaborator with a network of filmmakers who emerged from the MLF (Mouvement de libération des femmes). “Defiant Muses” revolves around the eternal question of how (and which) images are constructed and circulated, while interrogating the conflicts that emerge between acting a political position and translating it into personal action. Following Ariella Azoulay’s suggestion that archival documents “are not items of a completed past, but rather active elements of a present,”1 the exhibition rewrites history by reclaiming what gets suppressed. I spent hours in it, connecting the dots, shocked by how little I knew about these women’s stories, unsurprisingly, alas, themselves transmitted mostly by women.

Curated by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Giovanna Zapperi, the show—which opened in July 2019 at LaM-Lille before moving to its current, rather hidden location on the third floor of Reina Sofia’s Sabatini Building—is the result of several years of research. It reactivates, among much else, the materials produced and preserved by the Centre audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir (SdB), which was opened in Paris in June 1982 by the joint initiative of Delphine Seyrig, documentary director Carole Roussopoulos, and translator Iona Wieder. In 1975, the three friends had formed, together with Nadja Ringart, the feminist video collective Les Insoumuses, recently celebrated by the documentary Delphine et Carole, Insoumuses (2019), directed by Callisto McNulty, Roussopoulos’s granddaughter.

The show unfolds chronologically, in thematic sections. The layout is simple, without frills, with an impressive amount of documents on display. Black and white abound. There is nothing on Seyrig’s life before 1961, her year of birth as diva, marked by the release of Nouvelle Vague cult movie L’Année Dernière à Marienbad [Last Year at Marienbad] by Alain Resnais. In the film, projected in the exhibition’s opening room, Seyrig features as a glamorous and mostly silent mannequin clad in Chanel suits. As the curators remark in the catalogue, from then onwards “Seyrig’s initials, D. S., thus became synonymous with dé-esse, French for goddess.” The walls are lined with rows of framed stage photographs, documenting Seyrig’s subsequent, invariably seductive characters, constructed for the pleasure of the male gaze by directors such as Luis Buñuel, William Klein, Claude Régy, and François Truffaut. In contrast, the monumental, strawberry-red costume and feathered headdress worn by Seyrig in Ulrike Ottinger’s Freak Orlando (1981), which stands theatrically in a corner, represents the actress’s emancipatory collaborations with female directors like Marguerite Duras (India Song, 1975) and Chantal Akerman, for whom she played the protagonist of the cult film Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles (1976). Its chilling last scene is reproduced on seven monitors in Akerman’s installation Woman Sitting After a Killing (2001).

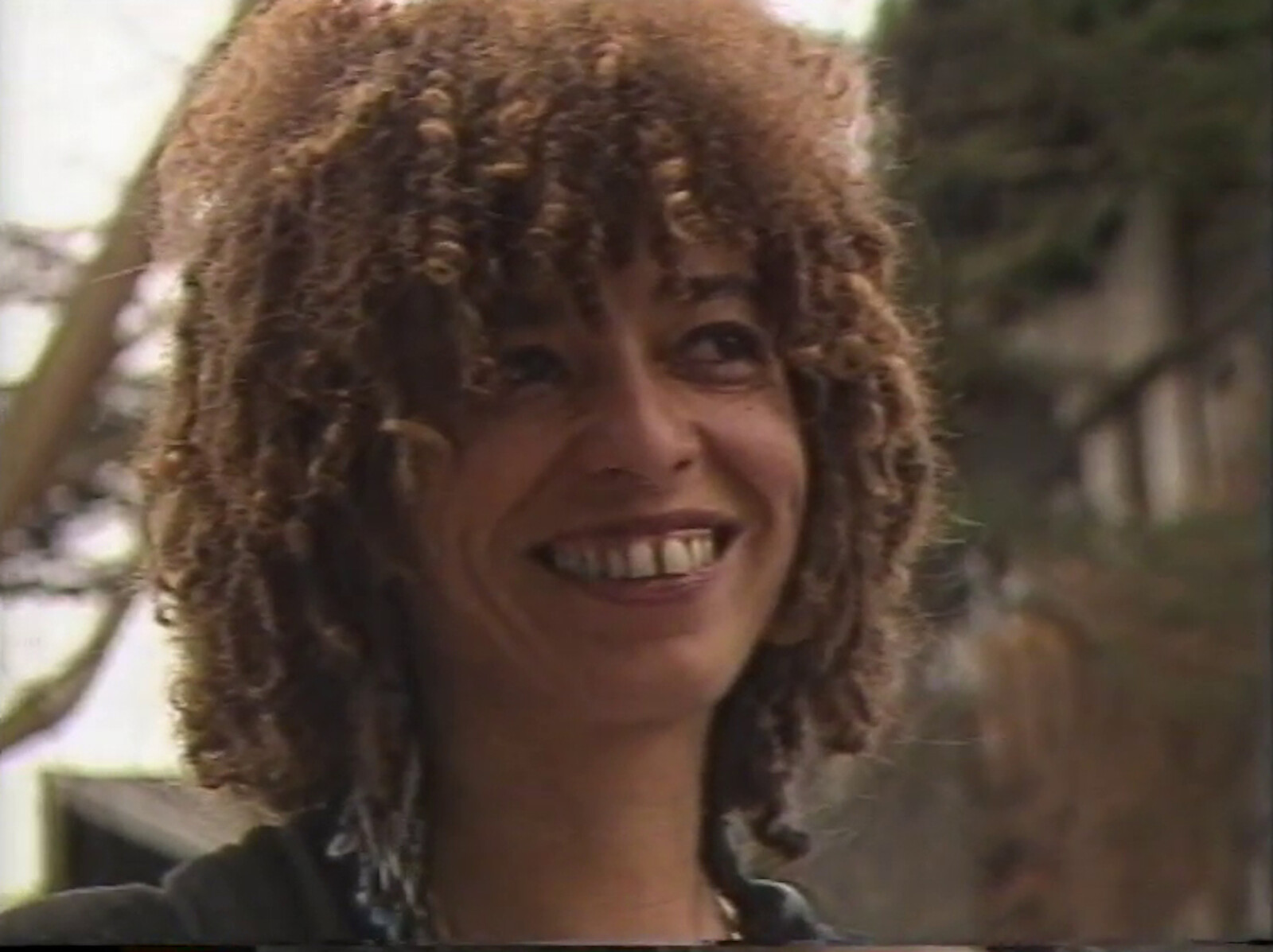

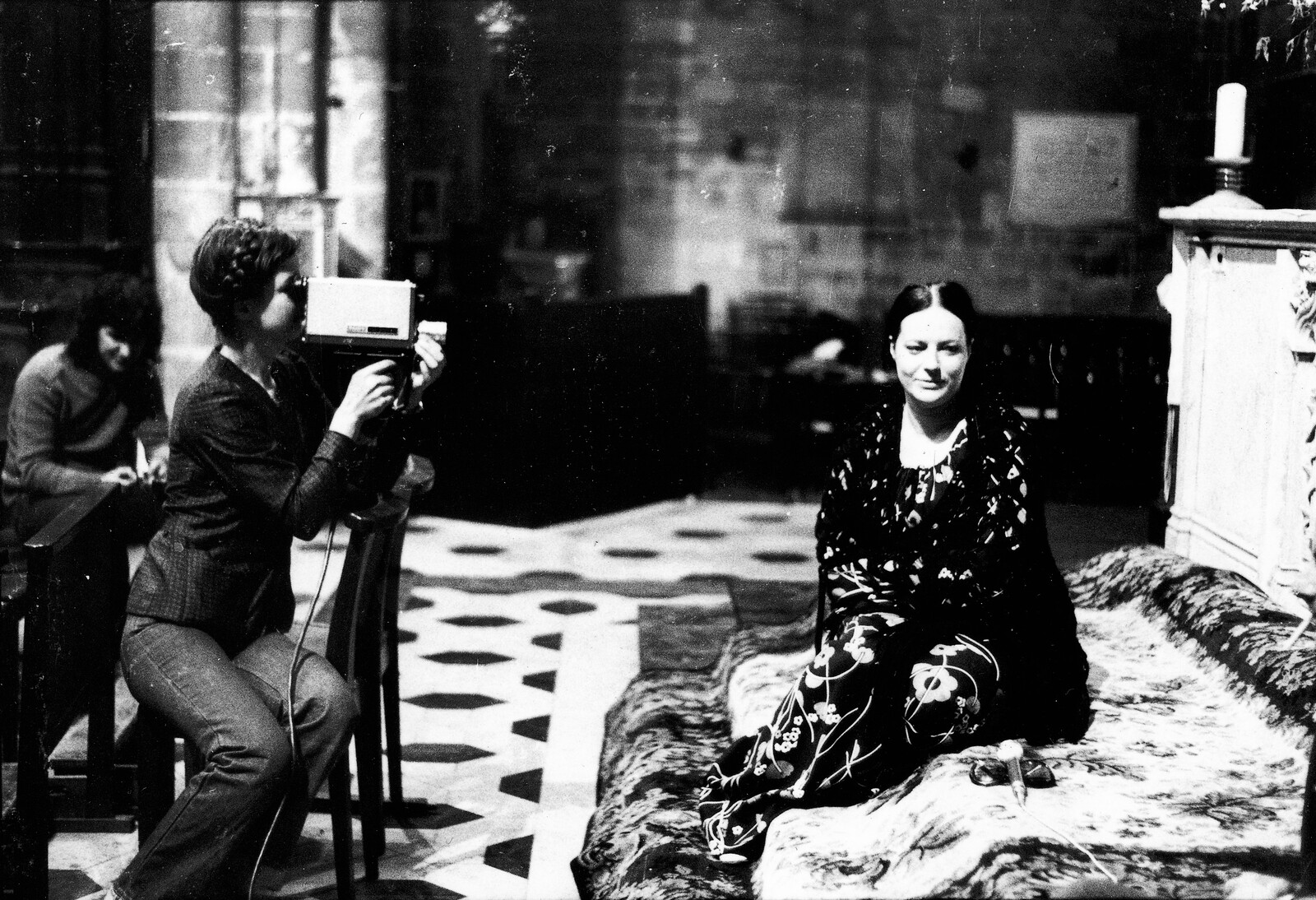

In the mid-1970s, Seyrig met Roussopoulos—the second French director to acquire a Sony Portapak, after Jean-Luc Godard—who offered free training sessions on shooting and editing videos in her Paris apartment. Seyrig then moved behind the camera. In her own words, “it was a revelation, an enormous pleasure, an incomparable revenge.” The exhibition shows how Seyrig’s work—both as an activist (in 1971, for instance, she signed the Manifesto of the 343, self-denouncing her illegal abortions) and as a generator of images, in collaboration with various allies (amongst them, her partner Sami Frey)—intertwined with the activities of the other members of Les Insoumuses, before and after the formation of the group. We see videos, made by Roussopoulos, charting women’s demonstrations, a meeting of FHAR (Homosexual Front for Revolutionary Action), a group of sex workers occupying the church of Saint-Nizier in Lyon (Les prostitutées de Lyon parlent [The prostitutes of Lyon speak out] (1975). Meanwhile, in Accouche! [Give birth] (1971) Wieder analyzes the violence performed on female bodies by the institutional control of reproduction.

In S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1976), Seyrig and Roussopoulos turn the camera upon themselves, reading and typing Valerie Solanas’s radical program for the elimination of patriarchal violence, while the lens zooms in and out on a TV screen and its brutal news: beatings at women’s marches in Belfast, repression in Argentina, civil war in Beirut. Maggy Moon (1974-2019), a new montage of scenes shot in Paris by Roussopolous and Seyrig, records an adaptation of Arthur Miller’s play After the Fall (1964), interpreted by a transgender cast. Marilyn is played by Parisian underground icon Marie-France, while Seyrig’s voiceover reflects upon the endless ways in which femininity may be constructed. Les Insoumuses collectively sign the hilarious agitprop video Maso et Miso vont en bateau [Maso and Miso Go Boating] (1976), whose title is a wordplay on misogyny and masochism, made in response to Bernard Pivot’s program “Encore un jour et l’Année de la femme, ouf ! C’est fini” [Women’s Year… thank goodness it’s over], aired on the French Channel 2 on December 30, 1975, where Françoise Giroud, the French Secretary of State for the Female Condition, was asked to respond to the satirical remarks of a male-only parterre. The original footage is cut, interrupted and counterpointed by ironic comments, songs, and applauses that disrupt the gross idiocy of the set-up.

The exhibition’s final segment regroups an ample series of documentaries on political struggles across the globe produced by Les Insoumuses (anti-Vietnam War and Black Panther movements; actions in support of political prisoners in Brazil, Germany, Spain, and the USA; the Palestinian cause) and the SdB (on the Coordination des femmes noires, the feminist activist Flo Kennedy, the movements of “women in migration,” The Women’s Conference in Nairobi in 1985). The impact of contemporary debates on decolonization and intersectionality is manifest here. In her contribution to the catalogue, Françoise Vergès asks readers “to imagine what a decolonial narrative of French feminist cinema would look like” if it could finally be analyzed “by identifying what it borrowed from the cinema of struggle in the South and what is forgot or passed over in silence.”2 It also presents some of the last projects developed by Seyrig, who died in 1990, aged 58. The exhibition closes on the video Pour mémoire (1987), Seyrig’s homage to Beauvoir a year after her demise. But to me it peaks just before, with her unfinished project for a film on Calamity Jane’s letters to her daughter, accompanied by a strikingly honest letter sent to her own son, Duncan Youngerman, in 1979: “I wanted to say so much with it about my mother, myself, the contradiction between femininity and independence, women’s extraordinary fascination with love, the desire for revolt and aspiration to dignity and respect, maternity, I wanted to say everything. And therefore couldn’t even begin.”

This review was first published on January 23, 2020.

Ariella Azoulay, “Archive,” in Political Concepts. A Critical Lexicon, Issue 1 (2011): http://www.politicalconcepts.org/issue1/archive/.

Françoise Vergès, “To Be a Woman, Not a Vision: Delphine Seyrig’s Feminist Quest,” in Defiant Muses. Delphine Seyrig and the Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s, eds. Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez and Giovanna Zapperi (Madrid and Paris: Museo National Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, LaM, Centre audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir, 2019), 152.