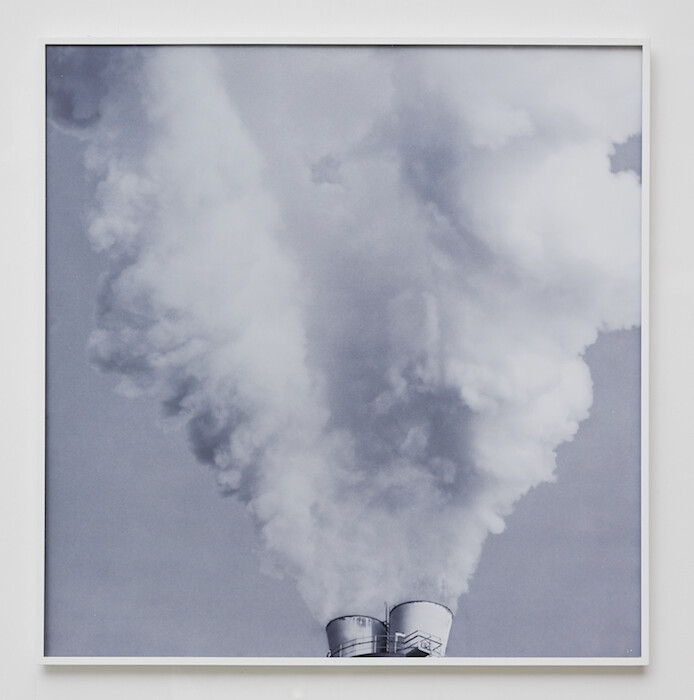

I had forgotten about The Day After until the North Korea/US missile crisis brought it back to mind with a bang. Aired in November 1983, the American TV movie terrified over 100 million viewers with its graphic images of a nuclear conflict between the US and the Soviet Union, leading to the manmade destruction of humanity. The poster image of the giant mushroom cloud, towering over the horizon, was everywhere. Maybe every era has a different cloud to fear, the current one being the capitalized Cloud propelled by Capitalism. And maybe that’s why the cloud “like an umbrella pine” that erupted from Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD and buried Pompeii under flaming rocks, pumice, ash, and sulfur gases still fascinates us. As evergreen disaster story and hyperfictionalized icon of a past apocalypse, it exorcises our fears of termination.

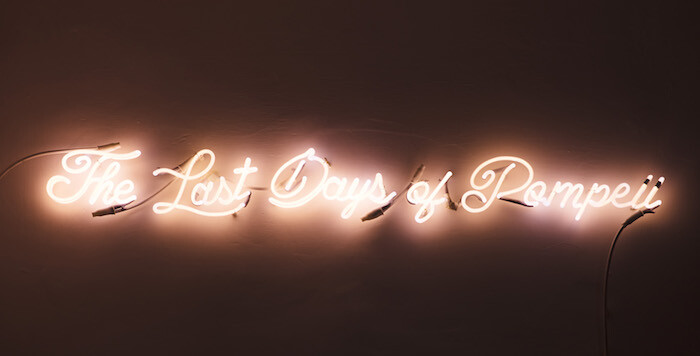

Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei [The Last Days of Pompeii], an Italian silent movie directed in 1913 by Mario Caserini and Eleuterio Rodolfi, was one of the first “Kolossals” of the disaster genre. It opens with a view of Pompeii’s busy streets, where peplum-clad citizens cross a city gate, flanked by two candid stelae. Its plot is based on a novel of the same name published in 1834 by English baron Edward Bulwer-Lytton, inspired by an eponymous 1833 painting by the Russian master Karl Bryullov, who, in turn, had been entranced by the opera L’ultimo giorno di Pompei (1825) by Giovanni Pacini—fiction follows fiction. “The Last Days of Pompeii” is also the title Delia Gonzalez chose for her second solo at Galleria Fonti, Naples. It’s spelled out in a pink neon sign installed above the entrance door, which infuses the gallery’s main room with a crimson glow, refracted on the surface of two monumental white stelae in drywall, The Osiris Gate I & II (2017), shaped after the negative space underneath arches in the wall. The floor, otherwise empty, is filled with the radiating electronic beat of Vesuvius, the last track—composed for the occasion—of Gonzalez’s just released album “Horse Follows Darkness” (DFA Records, 2017).

In the second room of the gallery, which has retained the intimate scale of a private apartment, the artist has hung seven framed paintings of identical size on paper (The Hour of Departure, The N° Five, Duelle (Leni), Jupiter, The Flowering of the Crone, Conjurer, Don’t Exclude the Moon, all 2017), mimicking geometric marble mosaics with illusionistic perfection, by means of graphite, acrylic, and golden leaf. Their recursive circular motif alludes to the moon and Isis as lunar goddess, but it also reproduces the oculus (oeil-de-boeuf window) inserted in the gallery’s entrance door, as another site-specific reference. For Gonzalez, antiquity and its dissolution are just a mood, a projection, an abstract fantasy, where the imagination is free to gallop. Images can be found elsewhere. Currently based in Athens, the artist describes her album as “a soundtrack for a Western movie,” because, after moving back to New York from Berlin with her son, she thought “America felt like the Wild West.” Hence her return to Europe and its post-ancient South.

“Napoli is a Pompeii that has never been buried,” Italian writer Curzio Malaparte famously remarked in his novel La Pelle [The Skin] (1949), a depiction of Naples as city of ruins after the World War Two bombings, the occupation by Allied forces, and the last (thus far) eruption of the Vesuvius, in 1944, when a 5 km-high cloud of ashes was first recorded on film. A room filled with bombarded and destroyed archeological findings lies at the core of “Pompei@Madre. Materia Archeologica,” another Neapolitan exhibition delving into Pompeii’s mythopoiesis. Spanning three floors of the museum, it is jointly curated by Andrea Viliani (Director of MADRE) and Massimo Osanna (Director of Pompeii’s Archeological Park), so that contemporary art and “archeological matter,” as the subtitle goes, are intertwined. On the third floor, Adrián Villar Rojas’s rocks and decaying food from the series “Rinascimento” (2015), presented as “submerged” in a white-cubish case, meet the viewer along with the original first diaries of the excavations, drafted in 1780.

In a section curated by Luigi Gallo, piles of books revive Pompeii’s literary allure; for instance, Malcolm Lowry’s novel Present Estate of Pompeii (1959) is open on its incipit, where the protagonist seeks refuge in the Restaurant Vesuvius to avoid seeing the ruins, too sinister for him. Photographs by Luigi Ghirri, Nan Goldin, and Victor Burgin, sculptures and installations by Maria Thereza Alves, Trisha Donnelly, Haris Epaminonda, Iman Issa, Maria Loboda, and Goshka Macuga, to name but a very few, open up iconographic dialogues with vases, everyday objects, fragments of furniture, burnt foods, frescoes, votive lamps, statues, figurines. The layout, inspired by the rooms of the traditional Pompeian house, enhances the artists’ fascination for the tangible presence of “matters” emerged intact from the past, thus echoing Bulwer-Lytton’s novel: “walls fresh as if painted yesterday—not a hue faded on the rich mosaic of its floors—(…)—in its gardens the sacrificial tripod—in its halls the chest of treasure—in its baths the strigil—in its theatres the counter of admission—in its saloons the furniture and the lamp—in its triclinia the fragments of the last feast—in its cubicula the perfumes and the rouge of faded beauty.”1 Aby Warburg’s “afterlife (or survival) of antiquity” shines on. On the first and ground floors, the exhibition infiltrates all the rooms of the permanent collection, each devoted to a single work. My favorite encounter, in homage to Gonzalez, was with Rebecca Horn’s installation Spirits (2005), where the artist’s casted skulls and circular rotating mirrors are now accompanied by a multitude of small anthropomorphic columelle, the funerary stelae originally bordering the main streets of access to Pompeii. Ashes to ashes, again and again.

Edward George Bulwer-Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1565.