The stakes surrounding this Whitney Biennial are, to say the least, high. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a biennial being under more pressure to signify, to mean, to produce meaning, to attempt to offer some special and tangible insight into our current moment. Instead, what the curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks offer is art. This is not to say, of course, that the art presented here is divorced from our current harrowing reality, by any means, but that it does not forfeit its unique transformative power in the face of it. Lew’s and Locks’s love of and faith in art is refreshingly unequivocal. Nor is this to say that the biennial they have curated is devoid of the political, insofar as one of the capacities of the political is to seek to imagine alternatives to the status quo. In the alternative…

The 2017 Whitney Biennial, the first to be organized during the run-up to a presidential election, makes its concerns explicit in the title of co-curator Mia Locks’s catalogue essay “Being with Other People.” The phrase expresses both an aspiration and a problem. On one hand, the exhibition offers several models of togetherness and collectivity, most poignantly in John Divola’s “Abandoned Paintings” (2007–8) photographic series of unfinished student paintings hung in deserted homes, and most pointedly in the Occupy Museums display of work by artists in debt. Yet such works are curatorially overshadowed by those that place emphasis on “other people.” Granted, in our uncertain post-election moment, artists and curators feel the need to respond to the imperiled conditions of life that many now face, especially people of…

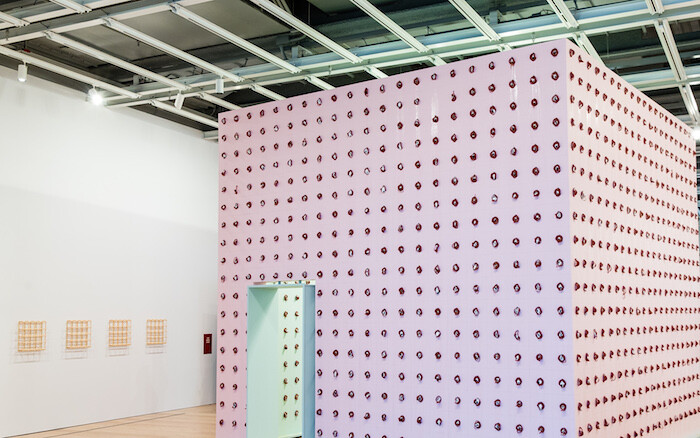

The stakes surrounding this Whitney Biennial are, to say the least, high. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a biennial being under more pressure to signify, to mean, to produce meaning, to attempt to offer some special and tangible insight into our current moment. Instead, what the curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks offer is art. This is not to say, of course, that the art presented here is divorced from our current harrowing reality, by any means, but that it does not forfeit its unique transformative power in the face of it. Lew’s and Locks’s love of and faith in art is refreshingly unequivocal. Nor is this to say that the biennial they have curated is devoid of the political, insofar as one of the capacities of the political is to seek to imagine alternatives to the status quo. In the alternative imagined here, an ideal diversity and gender balance reigns. Of the agreeably modest and negotiable number of 63 artists and artist collectives, this biennial possesses more artists of color than any other in its past. That diversity is not limited to ethnicity, gender, and geography (artists hail from as far afield here as Puerto Rico and Seattle, although Brooklyn dots many a biography) but also extends to media—even if a heavy emphasis is perceived to fall on painting.

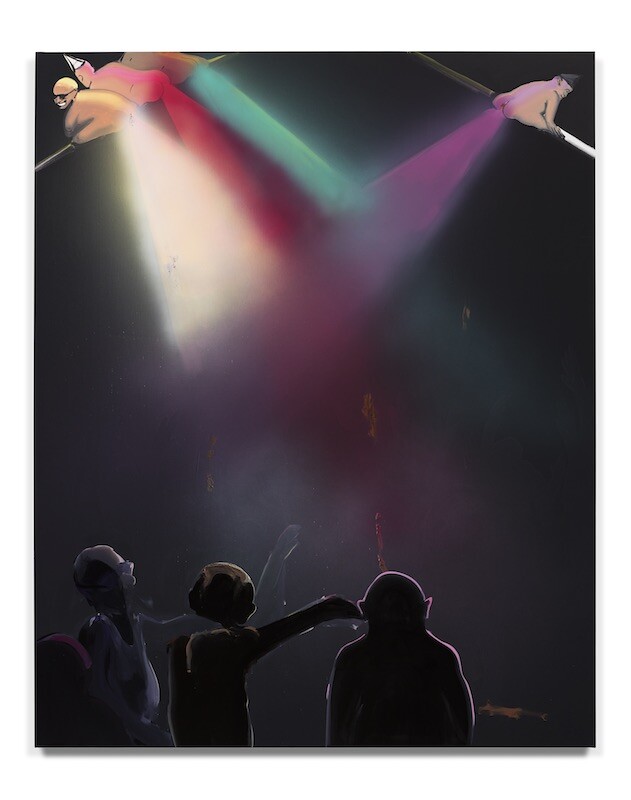

There is something here for everyone—from new media to institutional critique to video to photography to more traditional art-making practices, and so on and so forth. What is more is that it all feels pretty integrated and well paced (no punishing back-to-back videos, for instance). Focusing primarily on solo presentations of artists, as in one artist per space, the show is well-curated with more than one canny juxtaposition (two personal favorites were Leigh Ledare’s 16 mm film Vokzal [2016] of the public around three Moscow train stations with John Divola’s elegant “Abandoned Paintings” [2007–8] photos, which feature recuperated discarded student paintings in derelict domestic settings, and Henry Taylor’s big brushy paintings of black communities next to Deana Lawson’s elaborately staged, intimate portraits of black subjects). If painting seems to dominate the show—there are in fact only about a dozen painters out of the 63 artists—this is probably for a few different reasons: the most salient is that we have been trained to not expect to see too much painting in a climate of political crisis. It’s as if the moment shit hits the fan, painting, which is assumed to be the acme of artistic luxury, superfluous, or somehow post-(pre-?)political, becomes irrelevant. In other words, painting becomes a metaphor for art itself. As such, a rejection of it, at least on those grounds, is liable to replicate a conservative or reactionary logic, which presumes that we need to get back to, if not “basics,” then a patent lack of ambiguity, as if the latter were not the very quintessence of contemporary art. All that said, a fair amount of recent painting is not entirely innocent in the formation of its bad rap, which this biennial organically seeks to correct.

Earnest to a fault, painting could be said to carry on here as a metaphor, but this time, for the biennial itself, which probably helps account for its conspicuousness. Barring a few exceptions, the general spirit of this biennial is earnest, sincere, and totally committed. This spirit is not limited to the painting, but extends to everything from Sky Hopinka’s lyrically beautiful video Visions of an Island (2016), which is a portrait of Saint Paul Island in the Bering Sea, to Asad Raza’s Root sequence. Mother tongue (2017), an installation that consists of box-potted trees which are commented upon by wandering mediators, to Chemi Rosado-Seijo’s Jef Geys-esque transposition of a local grade-school classroom to the Whitney (Salón–Sala–Salón (Classroom/Gallery/Classroom), 2017), and a selection of works by Jessi Reaves and Sky Hopinka to the classroom itself. But nowhere is this earnestness more evident than in a great deal of the painting on view, from Aliza Nisenbaum’s colorful, richly patterned portraits to Shara Hughes’s florid and fantastical landscapes to Celeste Dupuy-Spencer’s endearingly wonky portrayals of everyday American life. I think this earnestness has less to do with the curators’ taste than with a will to register a recent late-Obama era cultural paradigm shift away from the tired, self-satisfied irony of the blasé privileged few toward something much more preoccupied with a shared human experience, which registers through sincerity, empathy, and nuances thereof. Curiously, this shift, which essentially moves from exclusion toward inclusion, is enacted precisely through excluding those who have traditionally excluded (through irony): white male painters. It just so happens that there is not one in the whole show. I have no idea whether this was intentional or if it just happened as a natural byproduct of the alleged paradigm shift. But here’s the thing: while I am happy to see this paradigm shift from irony to earnestness formally registered in a survey as important as the Whitney Biennial, I am also a little skeptical of its purchase in our current political climate. I am both scared and forced to acknowledge that Trump, his sinister administration, and the circumstances surrounding his election (not to mention Brexit and the refugee crisis) seem to have inaugurated if not yet another paradigm shift, then a general mood of radical uncertainty (as well as philistinism—indeed, isn’t it funny without being funny at all how fascism is actually a form of radical and humorless philistinism, such that to put to fascism, humorless, and philistine in the same sentence is tantamount to indulging in reckless pleonasm). An embrace of empathy, sincerity, etc., almost feel like markers of a halcyon period which was in fact just yesterday. This is not to say that they no longer matter—perhaps they matter more than ever—nor is this to imply, at all, that art should struggle to reflect its current moment, as in be intentionally topical. Rather, maybe when it does reflect its moment, that moment is already past. And that maybe this biennial might be a lot more elegiac than we think. I don’t know.

Nor do I have anything like an alternative proposal, but I do know that there were a few pieces in the biennial that made me wonder what the fuck I was looking at and these feel like they’re worth mentioning precisely for this reason. They include Jessi Reaves’s weirdly functional furniture sculptures, Tala Madani’s dystopian “pipi-caca” portrayals of male desire, Puppies Puppies’s disembodied gun triggers, Julian Nguyen’s elegant, renaissance-style, mutant beleaguered front-page paintings of The New York Times, Frances Stark’s screed-like suite of paintings of the pages of Ian F. Svenonius’s book Censorship Now! (2015), which poignantly advocates for censorship (I confess that I find its negativity spiritually edifying). But no work hit my optical WTF nerve as much as Jordan Wolfson’s virtual reality video Real Violence (2017), which consists of him bludgeoning, with baseball and foot, a man to a soundtrack of Jewish prayer. Anything but a fan of this piece, I mention it due to its stark, potential harbinger-like quality. It is sociopathic art for what, to all intents and purposes, is precipitously shaping up to be a sociopathic era.

The 2017 Whitney Biennial, the first to be organized during the run-up to a presidential election, makes its concerns explicit in the title of co-curator Mia Locks’s catalogue essay “Being with Other People.” The phrase expresses both an aspiration and a problem. On one hand, the exhibition offers several models of togetherness and collectivity, most poignantly in John Divola’s “Abandoned Paintings” (2007–8) photographic series of unfinished student paintings hung in deserted homes, and most pointedly in the Occupy Museums display of work by artists in debt. Yet such works are curatorially overshadowed by those that place emphasis on “other people.” Granted, in our uncertain post-election moment, artists and curators feel the need to respond to the imperiled conditions of life that many now face, especially people of color, refugees and immigrants, queer and trans people, women, and the poor—indeed the list stretches to include the entire planetary ecosystem, which is to say, all of us. Yet to fixate on otherness for its own sake, especially in the name of liberal hallmarks like “diversity” and “inclusion,” distracts from the hard work of “being with,” an issue that’s far from settled either in the biennial or in contemporary American life. The show has been amply praised for the many forms of otherness represented among its artists, but the far more difficult task of living with and among difference is not nearly as central to it as it could be. So what does the work of “being with” actually look like?

The exhibition offers various answers to this question. The strongest of these include Henry Taylor’s powerfully blunt paintings (such as The 4th, 2012–2017, and THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, 2017) about ordinary black life—an existence that must always contend with police violence—and Leigh Ledare’s Vorkzal (2016), three looped 16mm projections that, each in its own room, depict the haphazard traffic outside several entrances to a Moscow train station. By far the clumsiest version of “being with other people” comes from Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence (2017), a virtual reality film that presents the faux-ethical quandary of whether to look away from the gruesome image of a man being bludgeoned by a baseball bat. “Looking away” is not only the duller option in this otherwise drab CG cityscape, but one designed to make you feel bad, as if your revulsion were tantamount to a moral failing. It’s the equivalent of a pamphleteer waving you down on the street to ask if you have time to save the planet today (to which the answer, as any New Yorker knows, is not “no,” but “fuck off”).

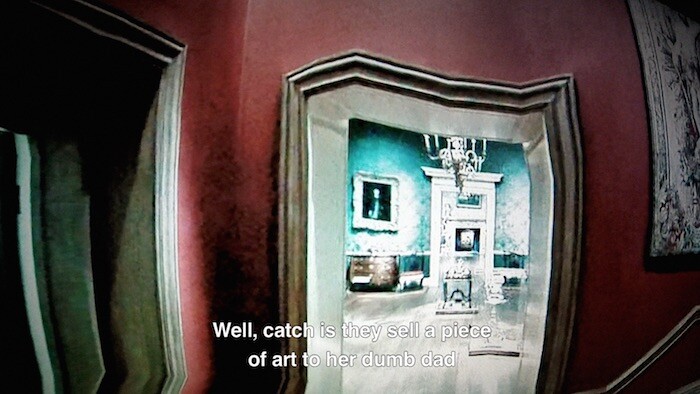

The film program, meanwhile, offers the most substantive responses to the issue of “being with.” (As with biennials past, this edition, despite its new location, has reproduced the rather tangential relation of the film program to the main exhibition. Though there are a few “crossover” artists, the Whitney has once again missed the opportunity to draw meaningful connections that would benefit both sides of the show.) Crucially, the films attend not only to what we see, but the more nuanced issue of how we see. Among the films, criticality is as urgent as ever; the issue of exploitation that surfaces in every accusation of “poverty porn” has not disappeared simply because we feel more intensely the problems that have long plagued us. That many of these works hail from a tradition of experimental film is significant in the current context. The avant-garde’s longstanding attention to form matters because it not only ascribes to form an equivalent importance to subject, but recognizes that the subject must be understood in terms of form. So while black and brown bodies predominate in front of and behind the camera, curators Locks, Christopher Y. Lew, and especially Aily Nash, who in recent years has established herself as an adept programmer with the Projections program at the New York Film Festival, understand that this is not enough. We must also examine the way we look at these images, and how we relate to them. To confront the issue of “being with” requires an accounting of the spectatorial relationship, especially in as wealthy and white an institutional context as the Whitney.

Key among the thirteen filmmakers they’ve programmed is Kevin Jerome Everson, who has made a prolific career out of depicting the lives of working-class African-Americans. The scavengers of Fe26 (2014) and the water department workers of Sound That (2014)—a diptych of films made in Cleveland—lead the viewer underground, opening manhole covers to plunge the depths within. It’s a literal and evocative play on one of avant-garde film’s most cherished ideas, that of an underground cinema. Here, though, it’s less about celebrating unruly or clandestine impulses, as in the heyday of New American Cinema, than the imaginative possibilities afforded by an inside-out view of the city. In these and other of Everson’s films, we see black individuals at work, often undertaking tasks with incredible speed (as in Fastest Man in the State, 2017), skill, or, like the doctor examining a woman’s vocal chord in Ears, Nose and Throat (2016), a proficiency mystifying to any nonspecialist. Everson has explained his aversion to what he calls the “zoo mentality,” where the people onscreen are presented for the audience to gawk at.1 When I asked him about this during a post-screening discussion at the New School in 2015, he elaborated. The people you see, he said, are smarter than you. They’re doing things you don’t know how to do. In Everson’s films, the discomfort that can arise in the audience stems not only from an uncertain center of dramatic interest, but also the sense that these individuals are indifferent to the audience’s pleasure, concern, or white liberal guilt. Simply put, they aren’t there for us.

This kind of refusal allows the people onscreen the dignity of their own perspective, their own way of doing things. It shatters the assumption, typical of traditional ethnographic film, that their images exist solely for the whims of the audience. As Trinh T. Minh-ha reframed the issue, it is a matter of speaking nearby, instead of for, the subject. Such a shift can unsettle the presumptions we bring with us to a work of art: the expectation that documentaries are informative, or that art should be aesthetically pleasing and/or satisfyingly “political.” Accordingly, James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s B-ROLL with Andre (2015) challenges its viewer through two slippery characters: the voice-disguised narrator obscured by a hoodie—a stock footage image listed, in the end credits, as “mysterious thug”—and the Andre he describes, an escaped con who leaves behind enigmatic clues of his whereabouts, including a GoPro camera that contains a trove of uncategorized footage. The narrator describes Andre with a mix of wonder and fear. He marvels at his friend’s inventiveness, including a pitch for a film about clever art thieves, but he’s also troubled by Andre’s farfetched ideas about achieving moral purity through HD resolution, and the “free-floating hostility” that attends his quest. Cloaked in shadow, and speaking through an amalgam of three voices, the narrator is as elusive as the man he tracks, someone who could be anyone, even perhaps Andre, and whose boundary-breaking film, much like the GoPro he finds, is a “jumble of moments smeared across time.”

The confusion in Wilkins’s film doesn’t prohibit language. Minh-ha’s insight, after all, was about speaking, albeit in a manner different from what the audience is accustomed to. Among the biennial films, voices speak both into and out of coherence. Sky Hopinka’s Anti-Objects, or Space Without Path or Boundary (2017) features the voices of two men, one trying out Chinuk Wawa phrases, the other gently correcting him. In the midst of their offscreen conversation, which, Rebecca-like, begins with one man describing a dream in which he was back in Oregon, the camera travels to Native American reservations in the Pacific Northwest, stepping through wet forests and, in one instance, pausing to view a mountain range topped by an electric pink and green sunset. The visual and linguistic journeys propel each other, in song and repeated phrases, to a place that’s both concrete and created in Hopinka’s brilliant imagining, a world where light streaks dance impossibly across the sky.

Cauleen Smith also visits sites of historical importance in H-E-L-L-O (2015), though the cultural map she draws emerges not in language, but in the call-and-response of musical instruments playing the five-note refrain from Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). In long shots that take full account of the musician’s figure (not to mention the impressive length of a contrabassoon), she tracks forwards and back, or sweeps in wide pans, to depict each musician planting what is effectively a sonic marker similar to the otherworldly visitors in Steven Spielberg’s film. With voices emanating from places like Louis Armstrong’s Colored Waif’s Home for Boys in Corona, Queens, and Preservation Hall, an institution of New Orleans jazz, Smith creates a chorus out of a far-flung diaspora.

The point of origin for this African-American community is indicated in Smith’s haunting Sine At The Canyon Sine At The Sea (by Kelly Gabron) (2016). Made in the immediate aftermath of the election, the film harnesses the fear and outrage of that moment, while also launching the viewer into a broader historical and extraterrestrial perspective. Smith’s alter-ego Gabron, last heard as a male voiceover in Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (1992), returns in full force. Over an NPR radio interview with white supremacist Richard Spencer, she corrects his simplistic, racist remarks with sharp-tongued indignation. What makes Spencer wrong is his small-mindedness, his concern only for those that resemble him. Smith links this to a brutal history in which people were sent away to the colonies, never to return, as we see images of the Door of No Return, the path to the slave ships taken from Goree Island, off the coast of Senegal. What do we do with people unlike ourselves? The answer, for Smith, is not to send people away, but to take the riskier step of keeping everyone in sight. Toward the end of the film, she offers this beautiful, big-hearted prayer: “So here’s my wish for us. Every sunrise and every sunset in the world all at once. For you.” In all its complexity, she recognizes the hard and necessary work of community, of living with. It is a task made all the more difficult when we understand, as Smith does, that the notion that some people can be ignored or expelled is the very heart of the violence we currently face.

Kevin Jerome Everson in Terry Francis, “The Ludic, the Blues, and the Counterfeit: An Interview with Kevin Jerome Everson, Experimental Filmmaker,” Black Camera vol. 5 no. 1 (Fall 2013): 184–208, citation on 196.