At the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, André Breton referred to a series of paintings by then-obscure artists Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff as being the “best and most truly Surrealist” of all the English contributions. Pailthorpe, a surgeon and trained psychoanalyst, and Mednikoff, an artist 23 years her junior, began living and working together a year prior, a collaboration they remained devoted to until Pailthorpe’s death in 1971. Their practice, which they termed “Psychorealism,” blurred the boundaries between psychoanalytic theory and art. By engaging with early memories and traumas, the artists believed their therapeutic practice would have widespread constructive and philanthropic use.

Pailthorpe and Mednikoff made notes about each other’s artwork in their psychoanalytic sessions, devising an elaborate taxonomy of “hieroglyphs” to decode their automatic writing and drawing, translating shape, color, and line into expressions of the unconscious. Due to the often explicit, erotic, or scatological nature of these interpretations, they were inscribed discreetly in the back of frames, or kept in personal papers. In “A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Reuben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism,” a survey exhibition at De La Warr Pavilion, several works have been mounted on freestanding metal frames arranged throughout the gallery, allowing the scrawled notes on the reverse of the paintings to be seen. Lengthy display captions for paintings and drawings, in addition to vitrines filled with papers, photographs, and research ephemera, capture their co-dependent and ambiguous relationship: identifying in public as colleagues, but projecting infantile desires onto one another in private notes.

The main analyses of their early work from 1935 to 1938 focused on birth, weaning, and sibling rivalry. Pailthorpe annotated images and wrote extensive lectures based on paintings by Mednikoff, diagnosing his aggression and anger as having origins in the Oedipal rage of the “ex-baby”: an older child who competes with both his father and his newborn sibling for the mother’s affection. A wall text explains that Pailthorpe described Arboreal Bliss, a painting made by Mednikoff in a session dated April 23 and 24, 1935, as “a symbolic breast-feed… [the] yellow hue reflects the warmth pervading the child’s body.” Pailthorpe’s paintings Crustacean Caress (1935) and Standbumptious (1937), meanwhile, visually embody her writing on “intellectual hermaphroditism”—a meeting of both male and female minds—by portraying liminal beings with male and female genitalia. Such hallmarks are found in much of the work from this period: biomorphic forms, yonic and phallic shapes, sweeping washes of color. Mednikoff’s The Red Arteries (1934) engages with the visceral fluidity of the bloodstream: deep red arteries course down the center of the canvas as if through a human torso, which he interpreted as his infantile yearning to swim inside his mother’s body. Mednikoff’s obsession with mother figures could also be configured in relation to the work of a contemporary fellow psychoanalyst, Melanie Klein, particularly the notion of the infantile desire to scoop, suck, destruct, and devour the breast.

In early 1938, Pailthorpe produced the “Birth Trauma” series, investigating how the trauma of birth had affected her own development. She believed that her mother “evicted her from the womb in order to punish her for kicking,” and that in her adult life, she was disciplined for “kicking” against convention—which she did. After growing up within the strict religious environment of the Plymouth Brethren, she worked in male-dominated environments as a surgeon, doctor, and criminal psychologist. The childlike, aggressive pictorial language of the “Birth Trauma” paintings—crying babies with the red open O of their angry, screaming mouths and smacked bottoms—sought to represent the pain and overwhelming disillusionment an infant feels in early life.

In the 1940s, the artists speculated on the causes of fascism (which they termed “the virus of hate”), proposing the “venting” of these childhood repressions as a preventative measure against mass violence. “Hitler and Mussolini,” Pailthorpe wrote in her undated and unpublished book Psychorealism: The Sluice Gate of the Emotions, “would never have become insanely dictatorial had they had, as children, ample opportunity to vent their infantile rages and to lessen the emotional tension imposed by fears and frustrations.”1 Their rigorous critical engagement with the connections between the psychical and the social predates another Kleinian analyst, Franco Fornari, who in The Psychoanalysis of War (1974) traced adult behavior in relation to armed conflict—particularly neuroses regarding the atomic bomb—back to infantile sources and psychotic fantasies.

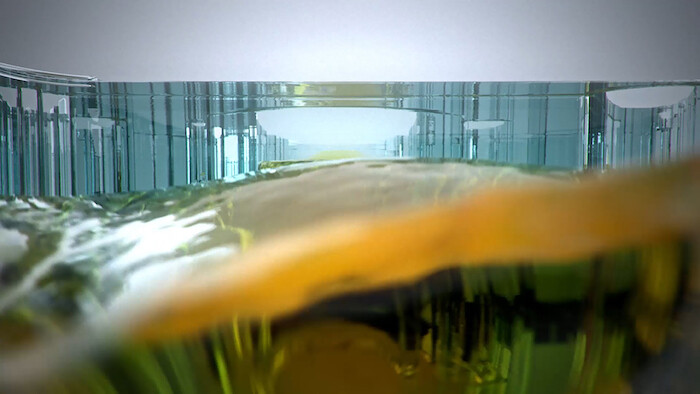

Projected onto a large screen in a darkened room on the first floor of the art center is Reproductive Exile (2018), a looping video by Lucy Beech that charts the fictional story of a woman who wishes to conceive by engaging in assisted reproduction in a medical facility in the Czech Republic. Striking footage of women soaking in baths of yellowish fluid, injecting fertility drugs, and touring dilapidated medical facilities is interspersed with images of viruses, MRI scans, and cellular imagery, many of which echo the organic shapes in Pailthorpe and Mednikoff’s works. Awash with scenes of liquidation—swimming, bathing, running taps—Reproductive Exile crescendos with a cascading wave of horse urine that overwhelms the screen. Female bodies, both human and animal, are symbolically tangled together. Hormones from a mare’s urine are used to thicken a human uterus. The womb is configured both as a symbolic psychic interior and biopolitical territory. While Pailthorpe and Mednikoff’s Psychorealism favored the muddy territories of the past, Beech’s work roots itself in the concrete conditions of the present to speculate on the ethics of possible futures. Surrogacy and subconscious drives are replaced by technology: the female reproductive system is controlled in the film by Eve, a computerized box that regulates unconscious, endocrinological processes. This notion of exile is figured as a palpable bodily and political expulsion: bodies are physically ostracized from their corporeal reality, stripped of their agency. Like the ur-woman the Eve box references—the first mother—these bodies are non-specific ciphers, understood only in relation to the booming fertility-industrial complex.

Grace Pailthorpe quoted in Hope Wolf, “A Tale of Mother’s Bones,” in A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Reuben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism, edited by Hope Wolf with Rosie Cooper, Martin Clark, and Gina Buenfeld (London: Camden Arts Centre, forthcoming in 2019).