September 20, 2017–January 7, 2018

Emma Lavigne’s “Floating Worlds” is the second in a “thematic trilogy” of Lyon Biennales exploring the “modern” (a perhaps onerous keyword issued by its artistic director, Thierry Raspail). Lavigne’s title references the Japanese idea of “the floating world” (ukiyo), a mindset originating in the seventeenth century which recognizes life as transitory and the value of sensory and hedonistic pleasures as release from mundane obligations. In various handouts, wall texts, and a catalogue essay, Lavigne also pegs to the curatorial framework Zygmunt Bauman’s distinct concept of “liquid modernity” as a recent period symbolized by flexibility and plasticity. As the infrastructures of social institutions liquefy, Bauman saw self-identification becoming a relentless task, suggesting the liquid modern was neither an aspirational nor entirely pleasurable mode but rather a state of transience and precariousness. The middle ground between these two ideas remains unclear, however, as the biennale is full of suggestive couplings and atmospheric liaisons.

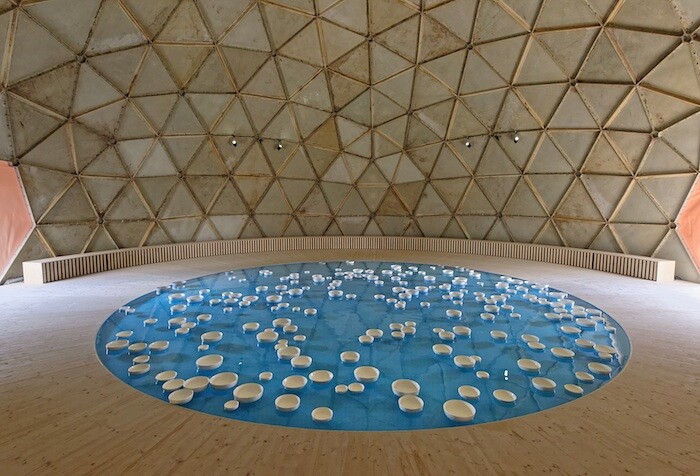

A Buckminster Fuller dome in Place Antonin Poncet is the centerpiece of the exhibition, sitting between the two main venues, the MAC to its north and La Sucrière to its south. Radome (1957) was designed as a shelter but also to enclose radar antennae, attenuating electromagnetic signals and protecting nearby wanderers from being struck by wayward beams. It’s a perfect symbol of the Cold War paranoia and dawning ecological awareness that defined the mid-1950s United States. Inside it, borrowed from the Centre Pompidou, is installed Céleste Boursier-Mougenot’s clinamen v4 (2017) an artificial hyper-blue pond across which dozens of white ceramic bowls drift and clink against one another with a hypnotic pitch and frequency. Radome’s radar shelter turned urban retreat begins a journey of body over mind that spans the biennale’s thematic sections which, Lavigne writes, “are conceived as walks allowing the mind to wander and dream.”(1)

Pairings of modern and contemporary works appear frequently. In the MAC, Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass and related Works with Nine Original Etchings (1967) are hung in line, an edition of nine etchings, seven of which detail the most important elements of the Large Glass (1915-23) and the final two of which show how it was before it was broken in 1927, and how it should have looked upon completion. In the same room, Yuko Mohri’s Moré, Moré [Leaky]: The Falling Water Given #4-6 (2017) scales up Duchamp’s original frame into three large wooden armatures, from which various jugs, vessels, and tubes are repurposed in a continuous circuit or rickety ecosystem, regulated by an electronic pump. As metal spoons hit steel piping it picks up Boursier-Mougenot’s clink, clink and adds a few drip, drips. Adjacent, David Tudor’s Rainforest V (variation 2) (2015) extends the arrangement. Domestic and industrial object assemblages are suspended from the ceiling and wired to speakers. This effect is spellbinding, and everyone around me wanders delirious. This walk is called “Ocean of Sound” according to the blurb, a thematic section that washes into to “Expanded Poetry” because there’s no clear delineation of space. It’s a conscious part of the exhibition design we’re told, rather glibly, “not to add walls, not to separate and divide when we are doing just that, building walls, all over the world.”(2)

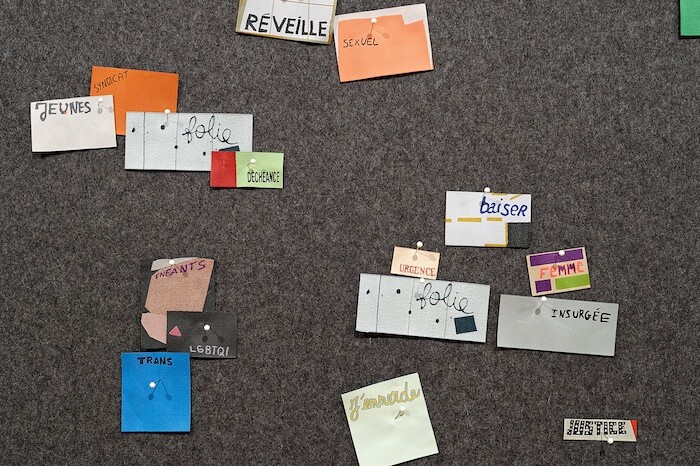

Next up, Rivane Neuenschwander’s Bataille (2017) is a large message board to which specially made fabric clothing labels are pinned. Each label has one word cropped from a recent political banner—“planète,” “sans,” “néolibéralisme”—and visitors are invited to combine and pin them to the board like concrete poetry or Brazilian Repente, an improvised lyrical performance. What results is a series of rather beautiful and jewel-like (some are woven with glittery thread) word collages. But rather than motivate collective action what the jeu de mots reveals is how difficult it is to reboot the predictable elements of familiar political slogans into anything fierce, invigorating, or new. Perhaps inadvertently, it presents a really good appraisal of the failing aspects of public demonstrations at the time when they are most needed.

Upstairs at the MAC, the obscurely titled “Archipelago of Sensation” section provides a psychedelic trajectory. Sculptures, paintings, and reliefs by Alexander Calder, Jean Arp, Dadamaino, Lucio Fontana, and Paolo Scheggi are pitched within Ernesto Neto’s fabric dreamscapes which, transecting the gallery horizontally, seem to relieve it of gravity. Beside Arp’s Pépins Géants (1937) there’s the opening to Neto’s Two Columns for One Bubble Light (2007), a large fabric chamber with a soft internal path tracing a figure of eight around two successive light columns. It feels distinctly womb-like here, around these primal tubes all warm and soft. Leaving it, Arp’s large stone sculptures appear different, like the external form of this impossible space I’ve just penetrated. Nearby, Calder’s dangling open forms, and the apertures in the Spatialists’ canvases all seem like possible entrances. These monochrome abstractions look newly porous and cosmic in a way I’d never quite seen before. I am inside them.

With works by 75 artists competing for attention, those manipulating sound were often the most successful. Fernando Ortega’s Flute Concert Film (2017) records a flautist playing Kazuo Fukushima’s Requiem (1956) in the Jules Verne wind tunnel in Nantes. The picture and pitch of this small wind circulating through this larger funnel is elegant and striking. Doug Aitken’s Sonic Fountain II (2013-15) is installed inside the tall cylinder of one of La Sucrière’s silos. Nine taps on a square rig drip from a great height onto an artificial pond below. The drips are sequenced, and their impact on the surface is caught by underwater microphones and amplified live on speakers in a composition by the artist. Aitken’s droplets plunk and echo in this satisfying water-world fantasia. Upstairs in La Sucrière, Camille Norment’s Prime (2016) is a sound piece concealed within timber benches on a balcony overlooking the river. Benches hum and reverberate through us with interpretations of Tibetan throat singing, Buddhist meditation, and African American gospel. Sounds are non-convergent; there is no harmony but it resonates differently to a Cagean sonic encounter. This is more a meeting of the spirits in an old sugar factory where the Rhône meets the Saône.

A dystopian thread runs through the biennale for those who seek it out, most obviously in works of film and video. Julien Discrit’s 67-76 (2017), also shown in La Sucrière, takes Fuller’s 1967 World Expo dome in Montreal as its backdrop. Using Fuller’s line “we are all astronauts” from Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968), Discrit revisits the pioneering architect’s interest in the universe’s parallel synergies, proposing that humans may rescue “Spaceship Earth” by converting its fluid dynamics into renewable energy. Shots of a female cyclist, a male river surfer, and a group of rowers close with the image of Fuller’s dome engulfed in smoke during a fire in 1976. Discrit’s piece is an elegy to Fuller and a bygone age of Whole Earth thought.

Close by is the projection of Bruce Conner’s film Crossroads (1976), grainy black-and-white footage of an atomic bomb exploding off Bikini Atoll in 1946, repeated 15 times at different speeds. Conner spliced together footage of this mushroom cloud as it rose eight miles above sea level and billowed outwards, recorded by 500 surrounding military cameras. As the action loops the soundtrack cuts from a Patrick Gleason collage of atmospheric sounds to a softer, more rhythmic organ composition by Terry Riley. Conner’s reworked spectacle is obscenely and inappropriately beautiful; watching battleships consumed by the explosion’s after-clouds feels both delightful and perverse. Conner wasn’t averse to the seduction of obliteration and exploring our complicated compulsions was arguably his life’s work.

Crossroads is sublime and unforgiving, a tremendous fusion that the biennale does not achieve, prioritizing pleasurable experiences and atmospheric liaisons over more difficult or weighty undertakings pertinent to the present day. And this is perhaps the issue with combining two almost irreconcilable concepts of buoyancy such as the ukiyo and the liquid modern in a curatorial framework: one will inevitably lose out. Lavigne’s sensitivity to works’ dynamics and her fluid choreography of them over several large-scale exhibition venues is rare in contemporary biennales, and is certainly commendable. But while many of her walks were absorbing, when senses felt exhausted I yearned for works that grappled with material elements and problems of the liquid modern as I understand it on the ground. It is now almost 20 years after Bauman first proposed his theory, when states of precarity, insecurity, and nomadism feel heavier and incredibly restrictive. Radome is the perfect emblem of a biennale that has no middle ground, but a bench around its circumference to sit and space and pond-gaze. Clink, clink, drip, drip.