I first came to the United States as an “international student.” At the risk of bothering the current administration, I stayed here. I remember every moment that I’ve learned something new about the culture and place I live in: class, labor, and racial relations, geography, history, the political system. I picked it up as I went along in an attempt to seem less foreign, never feeling the positive spin of the description “international” except on my university paperwork.

At the Carnegie International, I learned about an American cultural phenomenon I haven’t been privy to: the children’s television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, a staple of American childhoods which aired from 1968 to 2001. There’s a local connection—Mister Rogers was from Pittsburgh—but I learned about it from Alex Da Corte’s…

Jazz musician and musicologist Aaron Johnson moved around the Carnegie Museum’s Hall of Sculpture, playing a mixture of trombone and variously sized conches. It was the day after the 57th Carnegie International’s opening reception: Johnson was performing art collective Postcommodity’s From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home (2018), an installation inspired by Navajo sand painting. Treating the work as a graphic score, he followed the smooth accumulations of crushed glass, riffed off its rusty steel compositions, and its textured pockets of coal—materials that call up the city’s industrial past. The musician shifted between punctual releases and more subdued emissions that trailed off throughout the gallery, past the doors between the Carnegie’s Art and Natural History Museums. Contravening the hushed…

I first came to the United States as an “international student.” At the risk of bothering the current administration, I stayed here. I remember every moment that I’ve learned something new about the culture and place I live in: class, labor, and racial relations, geography, history, the political system. I picked it up as I went along in an attempt to seem less foreign, never feeling the positive spin of the description “international” except on my university paperwork.

At the Carnegie International, I learned about an American cultural phenomenon I haven’t been privy to: the children’s television show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, a staple of American childhoods which aired from 1968 to 2001. There’s a local connection—Mister Rogers was from Pittsburgh—but I learned about it from Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil (2018), a house made of neon lights and populated with a three-hour loop of 57 videos in which Da Corte and friends play Rogers as well as other characters, from Bugs Bunny to Big Bird. It’s a colorful, light-hearted installation that encapsulates the exhibition’s attitude, what its curator Ingrid Schaffner calls “museum joy”—the satisfaction of seeing art, in public, and the contemporary work of interpretation, of creating connections and making ideas.

Opting out of a thematic group show, Schaffner chose to focus the 57th Carnegie International not on a subject but on its tradition: the title, “International,” itself, here seen not as a theme but as a condition. The other condition of the show—it being hosted in the Carnegie Museum of Art, interspersed with the collections—becomes its other defining aspect. The exhibition is formally stunning. Some of the artists’ works benefit enormously from their placements. Jessi Reaves’s soft sculptural furniture pieces are shown in the architecture galleries, which are inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, surrounded by walls upholstered in a light brown fabric, the perfect environment to host them. (Reaves also has works on view at Fallingwater, Wright’s masterpiece not far from Pittsburgh.) Postcommodity are showing From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home (2018), an installation the collective call a “sand painting” made of steel, coal, and glass in the great Hall of Sculpture (at the opening, there was also a beautiful performance of a sole trumpet player, standing on the railing of the second floor above the Hall, playing, alone, to the empty space). Other works are flattened by their environment. Jeremy Deller reinstalls the video Breaking News (for Peter Watkins), which was his contribution to the 2004 Carnegie International, inserted via tiny screens into the small living rooms and minuscule libraries in the Hall of Miniatures in a presentation that is simply twee. More significantly, not far from Deller’s installation, Saba Innab presents What Is Unseen Cannot Be Broken (2018), a fragment from one of the tunnels used to smuggle food, construction materials, medicines, and other cutoff things into sieged Gaza. It’s a potent work about an invisible system of survival for Palestinians (Israel is repeatedly ruining such tunnels claiming they are used to smuggle arms) that loses steam in its display in the Hall of Architecture, a fragment of cement that becomes inconsequential next to the massive Gothic portals it shares a space with.

In the white cube spaces on the museum’s second floor are works that celebrate the International’s marvelous selection of work and beautiful displays. There are portraits by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, potent and direct; an attractive presentation of Ulrike Müller’s abstract enamel works; Zoe Leonard’s photographs of the Rio Grande hanging along the railing above the Hall of Sculpture, commanding the space in quiet contemplation. And yet, the feeling is that this is an exhibition that hasn’t figured out its relationship to the museum. This is a question picked up in “Dig Where You Stand,” a show-within-the-show organized by independent exhibition maker Koyo Kouoh, who, with a group of curatorial and research assistants, pulled out objects and artworks from the art museum and natural history museum that shares the building with it. While at times the show seems like a collection of curiosities (a birdhouse in the form of an English cottage! A nineteenth-century tea machine made of copper and ivory! A coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II!) it’s the only part of the International that asks some difficult questions about the museum. How are these collections amassed, what do they mean today, how could they be contextualized? For a major contemporary art exhibition in a historical institution, the International eschews such questions by directing its attention to itself.

Kouoh’s exhibition opens in a double display of Andrew Carnegie’s portrait: One made by Andy Warhol, Pittsburgh’s famous son (Andrew Carnegie, 1981); the other is Untitled (Carnegie) (1991) by Louise Lawler, a small crystal ball encasing a print of a photograph of two of Warhol’s Carnegie portraits hung in a café full of plants. A reminder: Carnegie was a union-breaker who employed his company’s chairman—another famous art collector, Henry Clay Frick—to crush the Homestead Strike in 1892, one of the most violent labor disputes in America. The histories of many—if not all—institutions, public and private, here and elsewhere, are complex. (It brings to mind Michelle Obama’s speech at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, in which she correctly—and chillingly—stated, “I wake up every morning in a house that was built by slaves.”[1]) Schaffner’s exhibition never acknowledges that the notion (and history) of the International may be part of a problem, not its solution.

I have friends, foreign friends, who have accents and visas and differing racial, linguistic, and religious backgrounds to the place they live in, who refer to themselves as “international” rather than immigrants. It just sounds better: “international” connotes free movement, choice, options—all the things migrants would like to have. And in the case of the 57th Carnegie International, “international” suggests an easy idea of art—so excuse me if I don’t participate in the museum joy. My criticism of the International is not its joyfulness, nor is it that it doesn’t have a stated theme. The fact that the title “international” came to define this exhibition is telling of the state of so many international exhibitions, with nebulous themes that avoid the simple truth that exhibitions in 2018 have a theme: the world we live in now. My criticism is that it’s an exhibition so lost in the luster of internationalism that it neglected to say something about where it’s from and what we may be able to learn from it.

In 1969, Mr. Rogers traveled to DC to testify in front of a Senate committee discussing budget cuts to public television.1 A video of Rogers’s address to the Senate circulated widely in 2017, after the Trump administration cut down funding to the National Endowment for the Arts. In it, Rogers describes his show: “We deal with such things as getting a haircut and the feelings between brothers and sisters, and we speak to it constructively.” He calls it “a neighborhood expression of care.” What I do, Roger says, is “give an expression of care, every day, to each child.” He is sincere and genuine, he is committed to his cause, and—like the children’s television show host that he is—he is patient. In front of Rogers, Senator John Pastore, the chairman of the United States Senate Subcommittee on Communication, says: “I’m supposed to be a pretty tough guy, and this is the first time I’ve had goosebumps for the last two days.” He elected to increase funding to public-access television by $20 million.

I’ve never watched Mr. Rogers but I’ve learned something from him: that you can make a claim for art and culture, for their place and stake in society. It’s a form of citizenship.

Jazz musician and musicologist Aaron Johnson moved around the Carnegie Museum’s Hall of Sculpture, playing a mixture of trombone and variously sized conches. It was the day after the 57th Carnegie International’s opening reception: Johnson was performing art collective Postcommodity’s From Smoke and Tangled Waters We Carried Fire Home (2018), an installation inspired by Navajo sand painting. Treating the work as a graphic score, he followed the smooth accumulations of crushed glass, riffed off its rusty steel compositions, and its textured pockets of coal—materials that call up the city’s industrial past. The musician shifted between punctual releases and more subdued emissions that trailed off throughout the gallery, past the doors between the Carnegie’s Art and Natural History Museums. Contravening the hushed decorum of the museum’s audiences and the over-determination of its architecture—with its two-tiered marble colonnade, decorative frieze relief, and sculptural casts perched on the balcony—Postcommodity’s invitation to local jazz musicians to interpret the work four times weekly forms a temporary fissure in the museum’s fabric. Sound transports the viewer in and out of where they stand, making the museum resound with narratives other than those encoded in its Parthenonic structures, neoclassical thrust, and industrialists’ aspirations.

Pittsburgh-born Ingrid Schaffner, who curated the show, invited artists to engage with the museum and city during the exhibition’s three-year development, a proposal which yielded diverse and often uneven outcomes. Counting 32 artists, collectives, and exhibition-makers, the 57th edition assembles works within the museum, avoiding the distracting dispersal across multiple venues to which major international exhibitions have lately been prone. This concentration allowed those works that engaged most directly with the museum’s collection to come into relief. Park McArthur’s Pits (2018), for instance, sought the provenance of larvikite—an igneous rock used in the building’s construction. Working with sound engineers, she collected field recordings from the Norwegian quarry where the rock is found. These are played from inconspicuously hung speakers in two unassuming locations in the museum: an empty passage between two galleries, and a ramp near the coat check downstairs. At first soft and slow, the sound builds and amplifies in a matter of seconds to occupy deeper and denser frequencies, revealing multiple textures as your ears attune to it. That Pits lingers with visitors testifies to the generosity of its invitation to listen to the sounds of people, footsteps, and whispers, and its desire—like Postcommodity’s activations—to ask what is at stake in listening to the museum resound.

McArthur’s contribution to the exhibition was also structural—she instituted gender-neutral bathrooms throughout the building. Curator Koyo Kouoh’s exhibition “Dig Where You Stand” offers another proposition for structural change in the permanent collection’s display practices. Substituting a corridor in the Scaife Galleries (home to the “African Art” and “Art Before 1300” collections) with artworks and artifacts bridging the Art and Natural History collections, Kouoh organized a new presentation in three thematic constellations—“Coloniality + Agency,” “Speculative Temporalities,” and “Mobility + Exchange.” Meaningfully mining the museum to generate critical juxtapositions, Kouoh’s diasporic assemblage features works such as Robert Gwathmey’s moving watercolor of Black Sharecroppers toiling (1940–41) or regionalist Thomas Hart Benton’s depiction of cotton-pickers loading up a horse-drawn cart in Plantation Road (1944–45), alongside representations of Pittsburgh’s industrial, commercial, and everyday activity in the 1950s, photographs by W. Eugene Smith, Margaret Bourke-White, and Charles “Teenie” Harris, and 1920s sculptural iron currency of Liberian Kissi people.

Kouoh’s strategy of anachronistic juxtapositions is reflected in other works, such as Saba Innab’s What Is Unseen Cannot Be Broken (2018), a concrete tunnel fragment reconstructed from a photograph of a partially exposed structure in Gaza. Placed in the Hall of Architecture, it stands out against the gallery’s Greco-Roman, Medieval, and Renaissance architectural casts and sculptural reliefs. The disjuncture between the artwork and the collection exposes a dialectic entanglement between the ideals and aspirations to permanence of the West, and their reverse, gleaned in the precarious and vulnerable fragment of a tunnel, at once shelter and passageway, in occupied Palestine.

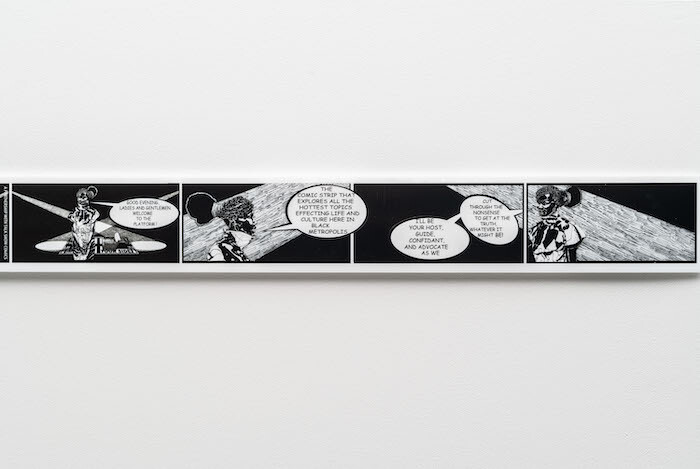

Schaffner not only invited these correspondences, but also shored up the museum’s own historical relation to the contemporary, conceiving of the site as a palimpsest of previous Internationals that connects past and current artists. Pittsburgh artists Lenka Clayton and Jon Rubin took up the mantle of this initiative, unearthing records of every rejected submission to the International between 1896 and 1931, when it was an annual painting show. Locally hired sign painters work through the list of 10,632 undated titles—such as A Portrait (there were many of these) or the more compelling A Lifting Fog—carefully painting, drying, and then giving the completed pieces away to visitors. Daily artistic labor on view in a museum has the unfortunate effect of becoming fetishized as a performance of endurance, with visitors lining up to receive, in due time, a vaunted painting. Spectacle is more ambitiously mobilized on the second floor, in Alex Da Corte’s Technicolor fantasy factory, Rubber Pencil Devil (2018), a three-and-a-half-hour video loop comprised of 57 short vignettes (an homage to this edition of the International and the number of varieties of local purveyor Heinz pickles) screened inside a house frame constructed from neon tubing. Da Corte and other performers navigate a vast repertoire of characters drawn from pop culture and cartoons. Mr. Rogers looms large—another nod to Pittsburgh. In a scene called “The Government,” a cartoon cat is curled up in a dark corner, targeted by the beam of a flashlight held by an unknown, menacing force. Never subtle but always nuanced, Da Corte’s sharp visuals are cut with a dose of sweetness.

The same could not be said of Karen Kilimnik’s Opening Night Performance (2018), which inauspiciously inaugurated the International’s opening. Working with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre School students, Kilimnik staged a collage of elements from the repertoire of turn-of-the-century Russian ballet choreographer Marius Petipa, by way of Sergei Vikharev’s reconstructions. The 20-minute performance—a flurry of precious compositions and extravagant costumes—preceded a screening of Kilimnik’s The World at War (2018), a tedious 25-minute edit of scenes from World War II films in which actors break into song and coordinated dance. This gendered divide—between young women who dance and men who wage war and sing—was already egregious, but the montage itself, poorly sutured, was a tired gesture at best.

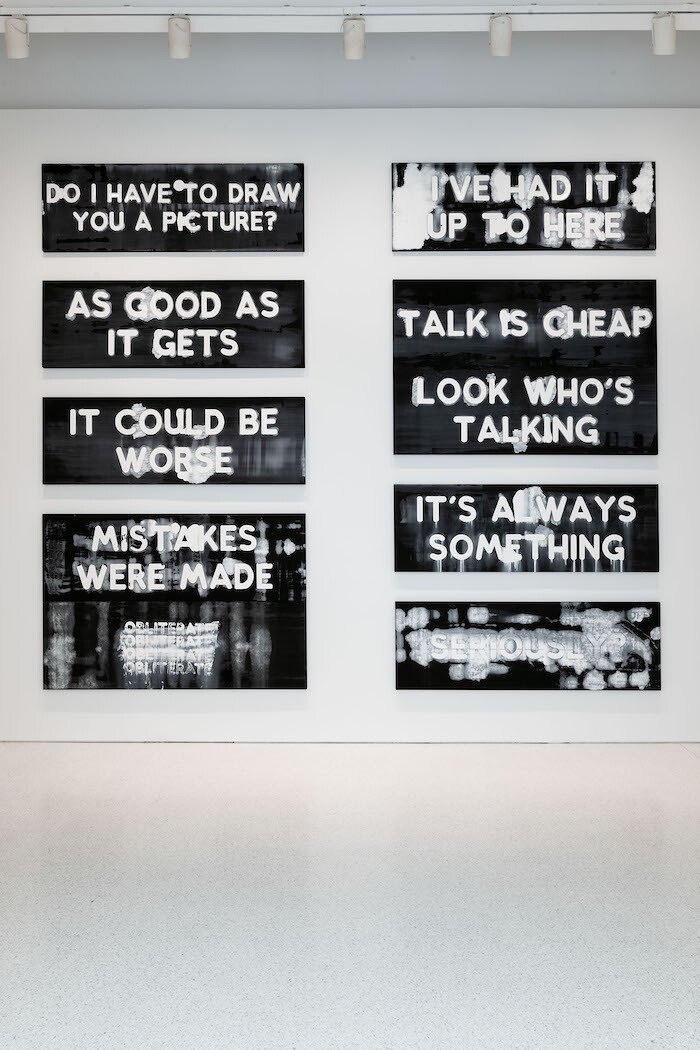

There are exhausted moments like this elsewhere in the show. Jeremy Deller’s Breaking News (for Peter Watkins) (2004), comprising miniature monitors screening Napoleonic and Jacobite war reenactments, was previously shown in the 2004 International, while Mel Bochner’s tongue-in-cheek textual provocations, such as Do I Have to Draw You a Picture? (2013), are by now quite familiar. In place of an organizing principle that might have made such inclusions less disparate (and underwhelming), Schaffner suggests that the museum itself—a site of convening for artworks and people alike—has something substantial to offer. The most salient works in the International call for audiences to share space as they spend time with the artists’ reevaluations and critiques of entrenched values on display amidst the institution’s holdings. In an introductory essay published in the accompanying guide, Schaffner exalts the exhibition’s potential, through such a mingling of publics, to generate what she calls “museum joy.” Her deeper proposition, however, arrives as arts and culture face national disinvestment from the Trump administration: that the museum can serve as a key site for social regrouping and assembly.