The editors of this publication keep a list of words and phrases that writers are to be strongly discouraged from using. On it are examples of curatorial bluster and authorial overreach (“In these times”), individually blameless words against which one editor maintains a personal vendetta (“oeuvre”), and a selection of quotes from canonical literature that have, by adoption into the catchphrase kitty of contemporary art, been entirely separated from their original meaning. So imagine my feeling when I discovered one of those blacklisted lines—Samuel Beckett’s “Fail again […] fail better”—mounted in giant steel letters outlined by LED lights on the façade of Athens’ new cultural center.

In fairness to Nikos Navridis, the artist responsible for transforming Beckett’s meditation on the void into a city-scale motivational mantra, his piece illustrates how a work of art can be interpreted in ways contradictory to its maker’s intentions. The artist is entitled to construe the line as he chooses, or it might even be that he wants local residents to reflect on the purposelessness of existence when buying oranges at the neighborhood market over which his sign looms. Either way, this reminder of art’s tendency to slip the leash of simple meaning offers a useful way to read this collaboration between the Hellenic Parliament and NEON foundation, a group exhibition which takes its title from novelist Arundhati Roy’s stated hope that the pandemic might serve as a “portal” between broken past and better future.1 It takes place in the Public Tobacco Factory—an architectural landmark owned by the Hellenic Parliament and renovated in the familiar manner of whitewashed walls, poured concrete floors, and period details—and features an impressive selection of work alongside 15 new commissions from artists including Adrián Villar-Rojas, Teresa Margolles, and Kapwani Kiwanga.

It is testament to the standard of work by more than fifty artists assembled here that it so often complicates the intellectual frameworks into which it is shoehorned. Take for example Steve McQueen’s Portrait as an Escapologist (2006), a pastiche of Warhol’s wallpaper that welcomes visitors into the central courtyard. Against Roy’s suggestion that we need to divest ourselves of the past and its “dead ideas” in order to move forward, this repeating image of the artist in shackles insists that historic injustices must be confronted and carried rather than cast off. Under the atrium’s elegant steel and glass-plate roof, Danh Võ’s untitled combination of a seventeenth-century German crucifixion in wood with a pavilion modelled on Chinese folk architecture likewise presents a more complex model of history’s construction than is afforded by the curatorial insistence that this moment, more than any other, represents a threshold between past and future. The commission does offer one lens through which to “reflect on the bicentenary of Greece’s War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire,” another of the show’s stated purposes, albeit that Võ’s commentary on history and identity does not obviously suit a straightforwardly nationalist narrative.

Given that this anniversary has recently been marked by a military parade through the capital and much saber-rattling on the border, the inclusion of Kutluğ Ataman’s Küba (2005)—an installation of 40 video interviews with Kurdish inhabitants of the eponymous Istanbul shanty town—carries political implications beyond rote rhetorical gestures to social justice. The decision to exhibit an exposé of systemic discrimination in the artist’s native Turkey might in this context seem a little too conveniently to align with a conservative government’s geopolitical agenda, especially when comparably direct critiques of Greece’s own authoritarian turn are conspicuous by their absence.2 And yet in its representation of violence and solidarity Ataman’s powerful installation (like Elif Kamisli’s notebooks, 2017–21, which document Turkey’s recent crises alongside her own experience of motherhood) refuses any such cynical interpretation. Indeed, these works are more likely to alert local visitors to the dehumanizing effects of the Greek authorities’ recent displacement of refugee communities in Athens.

So often do the works seem to disrupt the exhibition literature’s manifest intentions that it’s possible to wonder whether the subversion is conscious. In a room organized around ideas of “home,” I see trauma and forced imprisonment rather than “trust” in Robert Gober’s nightmarish Pitched Crib (1987); where a wall text reads “the untold story of ageing and care” into Apostolos Georgiou’s painting of a drunk or otherwise incapacitated man being undressed by a kneeling woman in heels, I see a more troubling dynamic of power and control. Yet these interpretative disagreements aside, “Portals” makes major work by a compelling combination of Greek and international artists—highlights include Jannis Kounellis, Shilpa Gupta, and Tala Madani—available for free to residents of a city not blessed with many contemporary art institutions. That much is to be celebrated.

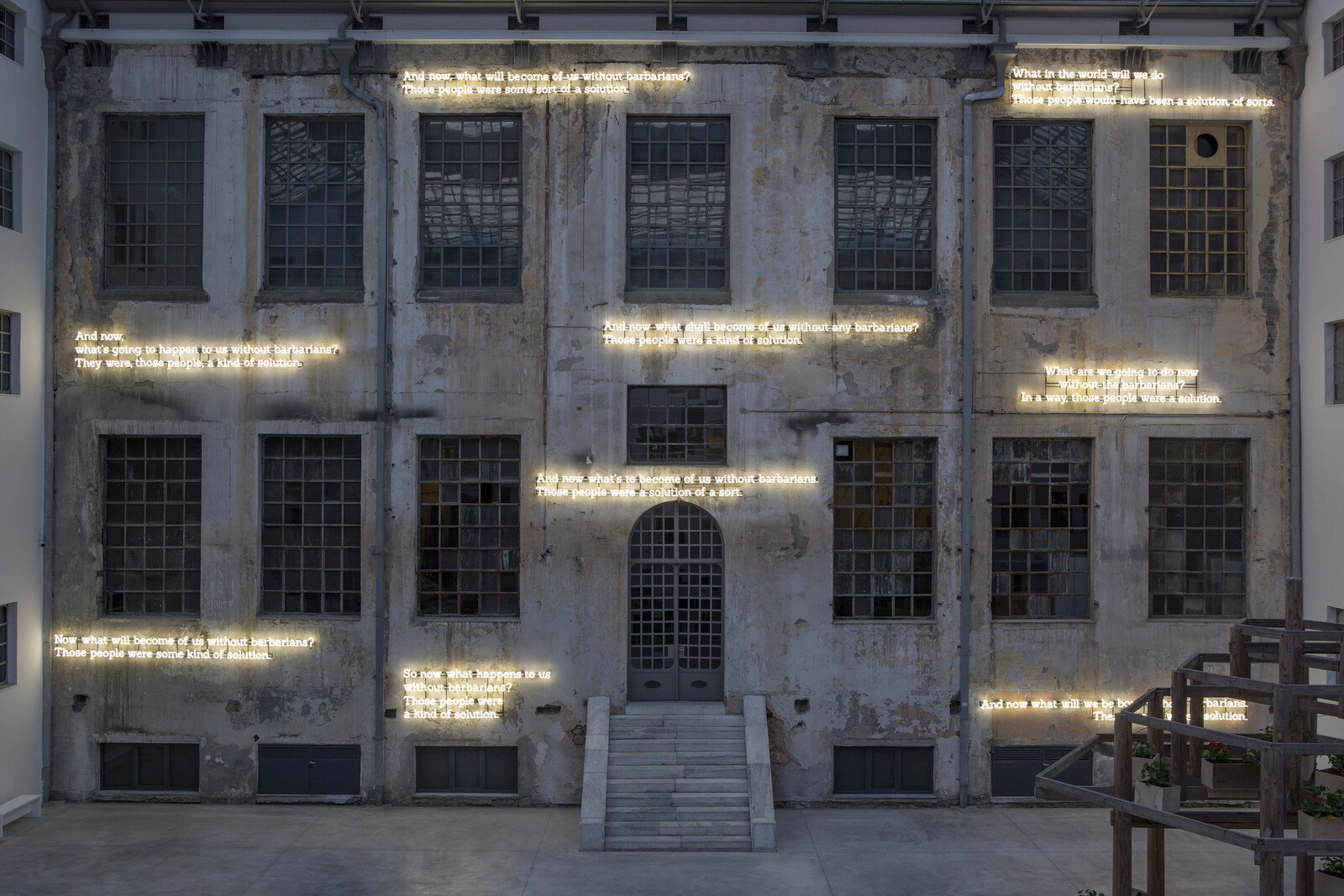

It is cheering, too, to be reminded of how art at this high standard is by its nature dissenting, resistant of easy assimilation into reassuring narratives. Back in the courtyard, one wall has been graffitied with variations in neon of two lines from another overfamiliar literary source, C. P. Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians” (1903): “Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? / Those people were a kind of solution.” Yet Glenn Ligon’s multiple translations exaggerate the lines’ polyvalency, recognizing that irony and ambiguity are strengths rather than weaknesses of any art that hopes to carry meaning through changing historical contexts. Here’s my own take: in these times, we shouldn’t assign responsibility for social change to an invasive other.

Arundhati Roy, “The pandemic is a portal”, Financial Times (April 3, 2020) https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca.

By contrast, NEON’s founder Dimitris Daskalopoulos has exercised his right to alter the content of Félix González-Torres’s untitled 1989 self-portrait—a list of formative historical events and their dates painted directly the wall—to include the phrase ΕΛΕΥΘΕΡΙΑ (“Liberty”). This is, according to the supporting literature, a direct reference to slogans shouted by Greek fighters (“Liberty or death”) during the War of Independence.