Those of us who willingly attend and return to Art Basel Hong Kong must still see hope in the global convolution of capital. If you don’t, call yourself a pessimist. When this hope is solely financial—which seems to be the case for many galleries—it belies a detached cynicism that ridicules the very nature of hope. For others, hope can be a polyvalent state of mind, geared toward the possibility of provoking social change in a hyper-capitalist context.

The global #MeToo movement finally had a breakthrough moment in China in March earlier this year, when Xu Gang, a former professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and the Sichuan Fine Arts Academy, was removed as the curator of the forthcoming 2018 Shenzhen Art Biennale following accusations of sexual and physical assault lasting decades. (The forthcoming “Xi’An Contemporary Art Exhibition 2018,” of which Xu acts as chief curator, has yet to respond.) While most galleries at Art Basel Hong Kong did not openly react to the news—Gang’s dismissal occurred 15 days before it opened—this fact provides an important context for the appreciation of works at the fair, in which booth presentations of defiant works by and about women stand out.

In the main galleries section, New York gallery Metro Pictures’s solo presentation of Cindy Sherman includes works spanning nearly four decades, from the lesser-known Untitled (Murder Mystery People) (1976/2000) to her acclaimed “Untitled Film Stills” series (1977–80) and the more recent “Untitled” works inspired by Golden Age Hollywood. Despite its modest size, this mini retrospective is perhaps the most comprehensive display of Sherman’s work ever staged in Hong Kong. As China reacts to the #MeToo moment, Sherman’s playful examinations of identity as artifice offer a timely reminder to avoid essentialized notions of identity and gender.

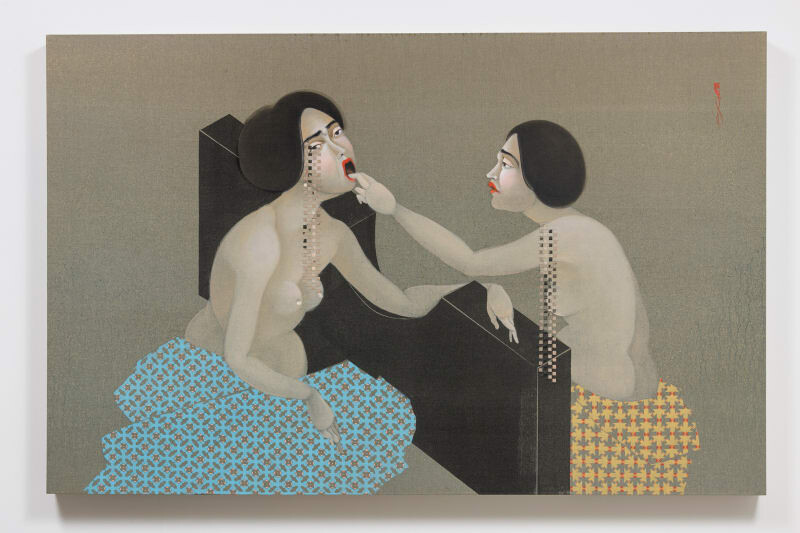

A further celebration of mixed identities, more pressing in tone than Sherman’s, can be found at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects’ solo presentation, also in the main section, of Hayv Kahraman, an Iraqi refugee who moved from Iraq to Sweden and now resides in Los Angeles. The hallmark of Kahraman’s paintings on linen is a nude female—it sometimes appears in multiples, as in Barricade 1 (2018)—wearing an expression of somber indifference, resisting the scopophilic male gaze. This body is hybrid: an amalgamation of figurative tropes from Persian miniatures, Japanese illustrations, and Renaissance painting. It is also vulnerable. The pictures’ surfaces are sliced to allow the reweaving of thin strips of other paintings into their material supports. Kahraman’s synthetic weaving offers a formal response to ideas of collective otherness, female trauma, and the pain of exile.

Over at the Discoveries section, London’s Project Native Informant presents Qatari-American Sophia Al-Maria’s video installation Mirror Cookie (2018), starring Bai Ling, a Chinese-American Hollywood actress attacked in her homeland as an “anti-China glamor model.” (A less subtle translation of the epithet would be “porn star.”) Installed above a vanity table and chair in the center of the mirror-lined booth, the video applauds the “bad” girls who have learned to endure a racist, patriarchal reality distorted by media culture. Bai delivers a series of statements direct to camera, from emotional self-help notes (“Know your worth,” “Make it shine”) to enigmatic, spell-like avowals (“You are love more than reality,” “#Magic”). The work is more than a defense of Bai, nor does it promote governmentality, under the guise of “confidence chic,” as remedy for the predicament of women today. Instead, by altering the image and voice of her subject with glitchy visual effects and pitch-shifted vocals, Al-Maria imbues Bai’s monologue with a sense of vengeance. Like a digital sister to Kahraman’s indifferent women, her distorted image defies the violent gaze Bai is subjected to in social media.

Although shown for the third consecutive year by Nanzuka, Toyko, it is always refreshing to encounter the “Harumi Gals” in Japanese artist Harumi Yamaguchi’s mesmerizing airbrush works. In the Kabinett section, three of her illustrations, from late 1970s to early ’80s, hang in a small room wallpapered with a giant reprint of a work depicting a woman’s mouth, the lips bright red, on the verge of swallowing a UFO against a mountain landscape. Born in 1941, Yamaguchi was inspired by the pin-up culture of the West, and in the 1970s became director of illustration for PARCO, a flagship department store in Tokyo’s Shibuya district that had a strong female focus, both in terms of creative leadership and target consumers. The women in Yamaguchi’s works, such as the one posing sensuously in a nightgown in Satin Woman (1978), are chic, displayed for consumption; but they are also tough, their skins rendered steel-like, their gazes more rebellious than enticing, their bodies more agile than docile. The commercial nature of Yamaguchi’s works complicates but does not negate their place in the women’s liberation movement in postwar—or indeed today’s—Japan. They feel especially prophetic in the context of the fair—don’t they look just like that girl clad in Versace walking past the booth in stilettos, looking for something to buy?

Taking inspiration from a different strand of pin-up culture—that which emerged in post-reform China in the 1980s and ’90s—Ma Qiusha’s “Page” series of cyanotypes (2017-18), at Beijing Commune, is a quiet reflection on female representation in popular culture from a transitional period in modern Chinese history. (Her choice of medium also pays homage to the history of photography by women: Victorian botanist Anna Atkins is commonly regarded as the first woman photographer in the world for her cyanotypes of British algae.) Born in Beijing in 1982, Ma’s practice is largely informed by the ideological gap between her and her parents’ generation, particularly regarding gender perception. Ma folds and reproduces old pin-up photographs as cyanotypes, which gives them a blue tint—a color that signified labor and harmony in pre-reform, socialist China. Echoing Yamaguchi’s illustrations, Ma’s reprints hint at the link between capitalism and the (exploitative) representation of women, but her reflection on these images connote a skeptical view of mass-media femininity that feels particular to her generation.

My decision to only highlight works by and about women is not meant to polarize or exclude, but to mobilize. The dismissal of Xu Gang marks a beginning of a cultural shift in the region. Considering China’s rise in 2018 to the world’s second-largest art market after the United States, the artistic context in the Asia-Pacific region is only growing bigger and faster, producing ever more spaces of employment and places for audiences to encounter (and collect) art and ideas. It feels necessary to take this moment to consider our individual and collective agencies in affecting change in power structures that demand urgent revision.