I fell into a Star Trek hole during the pandemic. That period was saturated with the overwhelming nausea I felt watching people with power respond disastrously to the crisis, both at the micro level of small art institutions and the macro level of national politics. By comparison, the people responsible in the Star Trek universe—Worf, Dax, B’Elanna Torres, Jean-Luc Picard (maybe not Riker, he always struck me as a bit lecherous)—seemed principled and empathetic. It was like Pepto-Bismol for the mind, a thick, bubble-gum pink pharmaceutical relief to an on-going shitshow. The series’ version of reality included an intact concept of the future and clear protocols for every kind of existential crisis. I found that, given the circumstances, I could ignore the Federation’s institutional resemblance to the United Nations and its problematic and unexamined investment in rationality.

Everyone deals with future-dysphoria differently, but a recent group exhibition at the Uppsala Art Museum, “A Posthumous Journey Into the Future,” struck me as a rich study of the alternatives to escapism. It presents the work of nine artists whose works consider the intractability of the future. Curator Rebecka Wigh Abrahamsson justifies the ensemble as an example of archipelagic thinking, a notion proposed by Franco-Caribbean writer Édouard Glissant to think about the future without relying on monolithic or coherent concepts of territory and self.

Take, for example, Eglé Budvytyté’s gorgeous choreographic video, Songs from the compost: mutating bodies, imploding stars (2020). Four dancers in their twenties dressed in ripped and faded cotton, silicon prostheses, fake fur, soft kneepads, and improvised chest binders melt together ingloriously on the floor of a soft green lichenous pine forest. They fold over a pale sand dune in the Curonian Spit in Lithuania, opening their chests wide to the sky, hands dangling without ambition. Is this hedonism or death? Budvytyté’s video suggests that even asking this question betrays an anthropocentric incapacity to grasp the truth of biological existence, namely that it is cyclical. The artwork’s soundtrack is a synthesized voice and tone composition drawing from writing by the renowned evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis. “Natural selection eliminates and maybe maintains,” Margulis argued, “but it doesn’t create.”1 She spent her life proving that symbiosis drives evolutionary change, rather than neo-Darwinian notions of competition. The future, for a symbiotic thinker, cannot be taken away from the weakest by the strongest. It is the stuff being pounded into microscopic particles by the waves, digested by bacteria in a mossy ditch, and gestating slowly in the folds of any given large intestine.

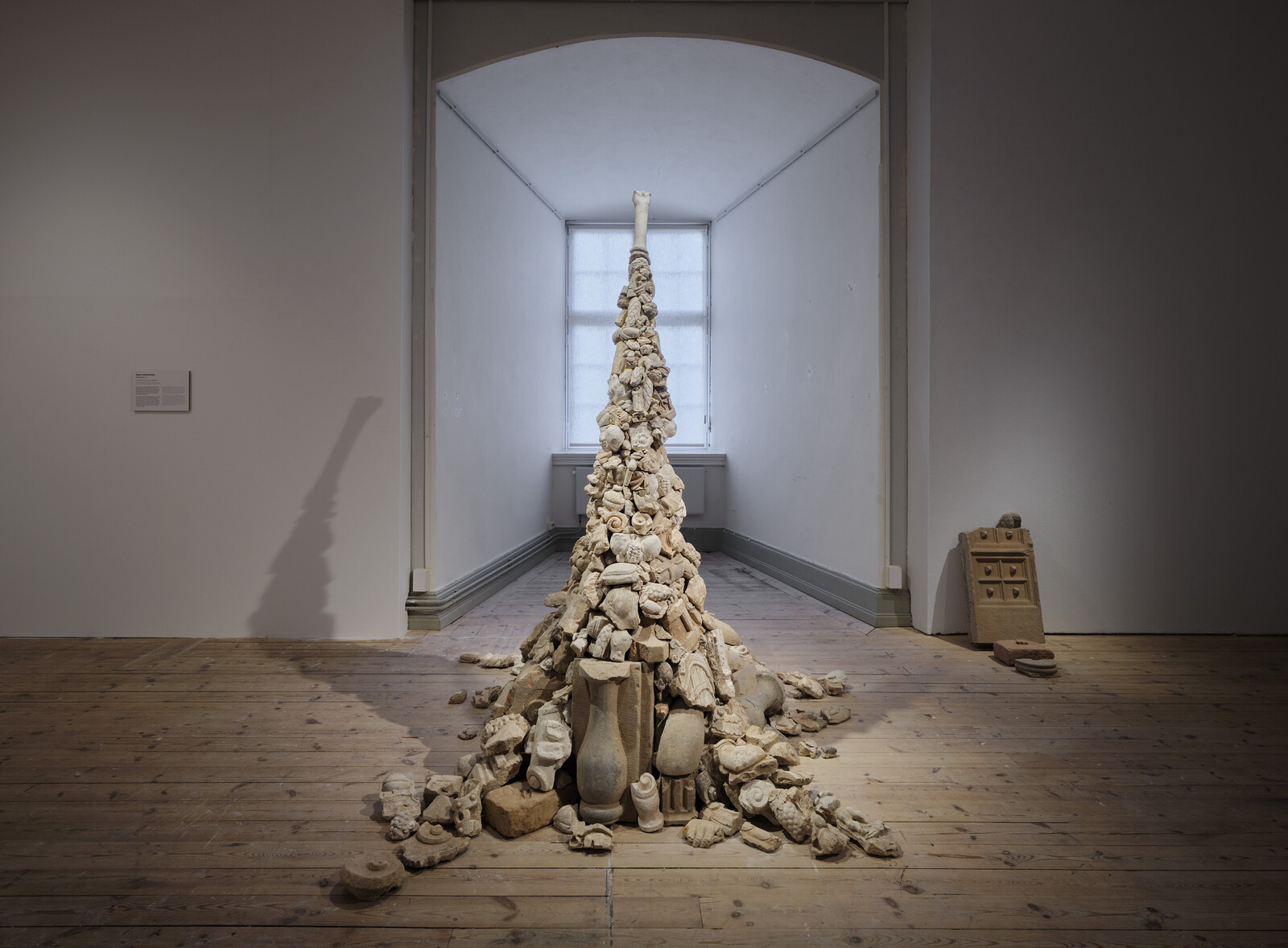

Gnesta-based artist Signe Johannessen’s site-specific sculptural installation, Re-resurrect (2022) is less visceral yet equally irreverent of existential hierarchy and temporal linearity. She collected the stucco and stone rubble from a sixteenth-century church that was once part of the Uppsala Castle and which is now home to the art museum. When the fortress was renovated in the 1940s, the fragments of human bodies, gargoyle heads, and ornamental, vaguely vegetal architectural flourishes were excavated from the surrounding grounds and stored in the basement. Johannessen cast some of the rubble in new plaster and mixed it with older pieces to form a large pile in the exhibition space. The pile is shaped like a monumental tomb sculpture, with one section arching upwards like the bow of an ancient ship—which makes sense, given that ancient Scandinavian cultures buried their dead in vessels or used them to send burning human remains out to sea. “What is the potential of the posthumous in a broken world?” the artist asks in the exhibition brochure. With Johannessen’s work in mind, that question might become: “What to do with irreparably injured ideological forms when nothing convincing is available to take its place?”

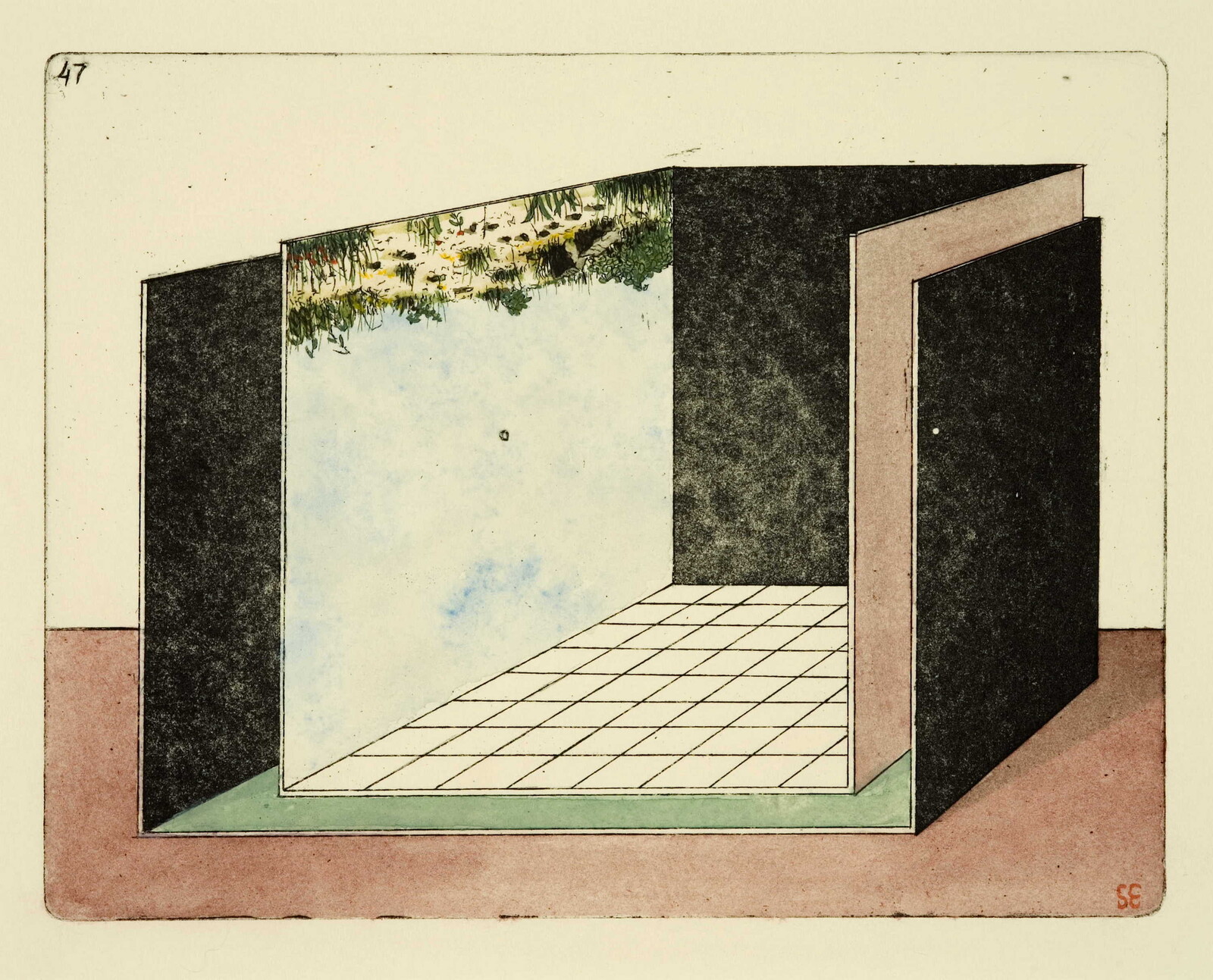

Though conceived—successfully—as an archipelago of projects, “A Posthumous Journey Into the Future” sets out to propose contemporary artistic responses to one particular artwork, The Secret of Kullahuset (1971) by Swedish artist Sten Eklund. Recalling Marcel Broodthaers’ elaborate production of fictional archives, Eklund’s project comprises fifty-three hand-inked etchings, several architectural prototypes and stained glass works, and a large quantity of notes. These elements purport to document a journey undertaken in 1849 by a young student of botany determined to follow in the footsteps of Carl Linnaeus, inventor of the taxonomic system that classifies organisms by genus and species called binomial nomenclature. (Linnaeus infamously expanded this system to classify humans by subgroup based on racial characteristics.) What this young make-believe Linnaeusian acolyte finds on his journey to the North is a futuristic settlement that has been inexplicably abandoned by its inhabitants.

One of Eklund’s meticulously drawn etchings shows six white monolithic forms rooted to the ground, tufts of grass gathering at the base of each featureless rectangle. (The monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey springs to mind here.) Though they are positioned like sentries along a promenade, there is nothing save a weak blue sky at the apex of their formation. Other framed works depict enigmatic production facilities, an empty glass greenhouse, and detailed plant studies of what appear to be ordinary weeds. Eklund—like many of the works in “Posthumous Journey into the Future”—makes the madness of Linnaeus’ obsession with taxonomic order palpable by simultaneously reproducing its aesthetic and excising its truth claim. The future has already been built and abandoned.

Dick Teresi, “Discover Interview: Lynn Margulis Says She’s Not Controversial, She’s Right,” Discover (June 17, 2011), https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/discover-interview-lynn-margulis-says-shes-not-controversial-shes-right.