Cristina Tufiño’s “Dancing at the End of the World” presents a grouping of drawings and sculptures that probe the violent effects of digital convenience and the gig industry. With pastel-glazed ceramic sculptures that feature anthropomorphized objects, feminine body parts, and cast-off keyboards, Tufiño adopts sex work as a metonym for the exploitative nature of the online economy. With an unsettlingly sweet aesthetic, she wonders about the consequences of using algorithms to mediate the instant gratification of desire on a vast scale.

In Constellation Sunset (Cubetas del Atardecer) (all works 2019), eggshell-blue arms lithely jut at rigor-mortis angles from two buckets filled with baby’s breath—the flower of innocence. A ceramic head of the same color is an eyeless but coiffed witness to the arms, which may be her dismembered limbs, her torso and legs unaccounted for. Peppermint Hippo (5) features two ceramic feet cleaved from an otherwise absent mint-colored femme, tied up with festive ceramic ribbons jamming a shrimp cocktail of long swollen toes over the edge of stripper heels a few sizes too small, highlighting the vulnerability to violence and the physical toll of desire-fulfillment work.

On the opposite wall, Bocaccio, a ceramic relief of a hand emerging from an arm-shaped keyboard suggests a Spike Jonze meets Franz Kafka ambivalence of separation between human and machine. In a dissociated and disembodied free-for-all of web-based signs and services, is this the anonymous hand of a perpetrator or victim?

There is an unsettling darkness that comes from the objects’ arrangement, which is eerily similar to a crime scene. Functioning as aestheticized, doll-like referents, the Easter candy–colored body parts in Tufiño’s work are clearly not meant to invoke anyone’s literal flesh. When combined with cutely anthropomorphized buckets, they seem to suggest that the human and non-human forms have achieved similar levels of personhood, and maybe therein lies the true criminality.

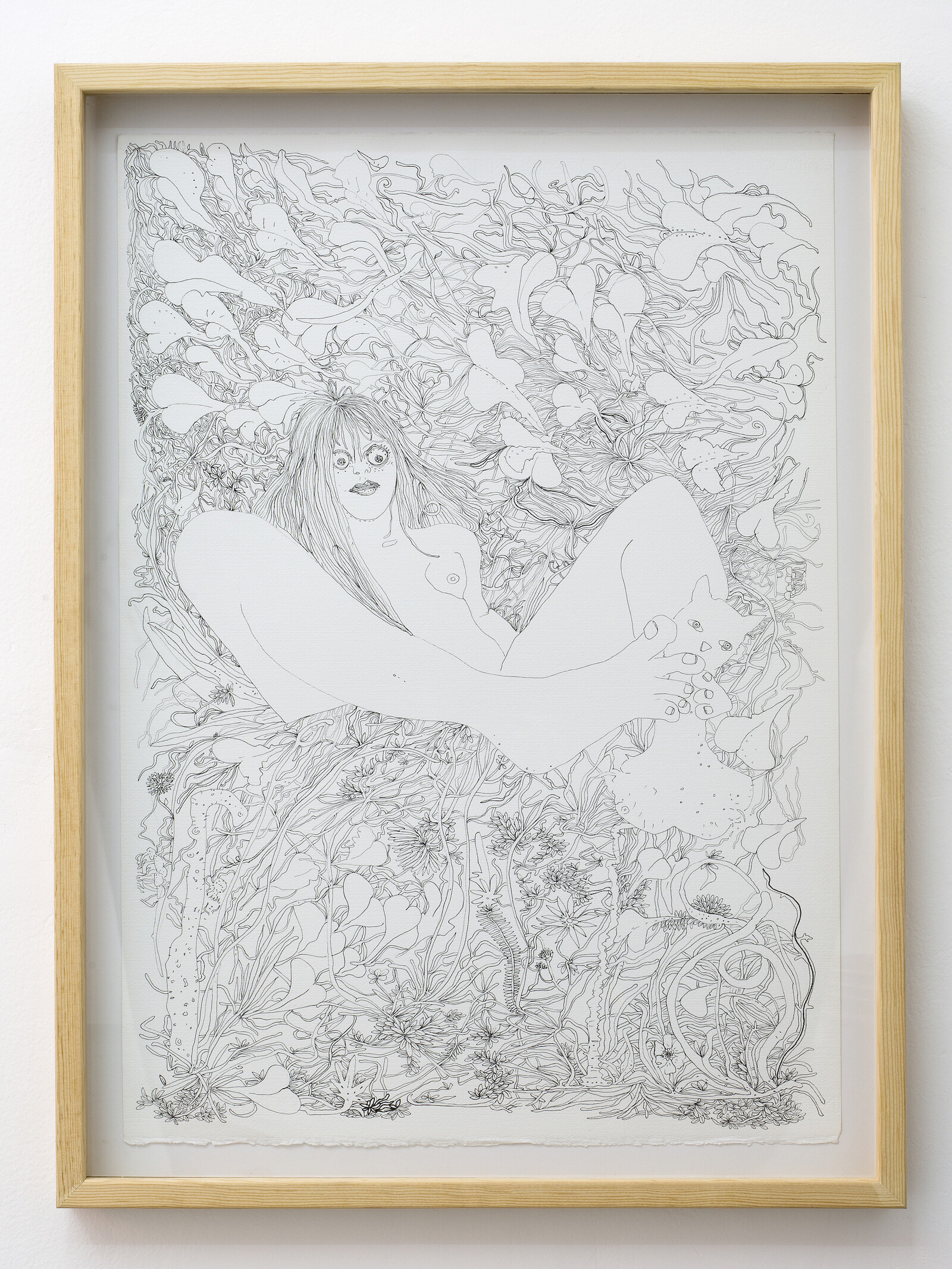

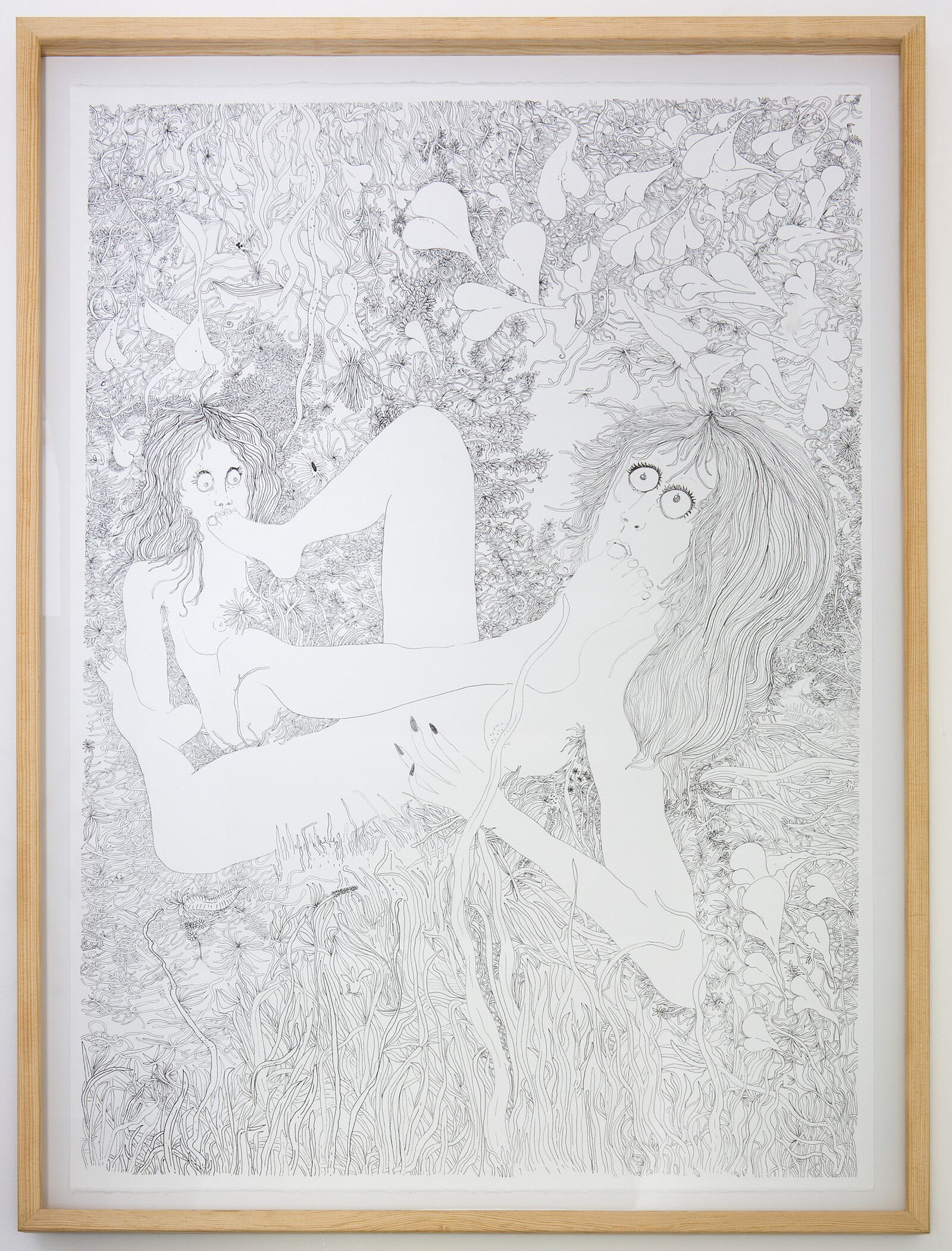

In Tufiño’s feverish drawings (Bad Kitty and Progeny), blasé kitten-headed phalluses comically suggest the extreme effects of tech-fueled pleasure-principle run amok. They depict wide-eyed women in wild gardens pleasuring either themselves or an amalgamation of the internet’s two most common figures, kitty cats and dick pics.

Upstairs, the exhibition’s pace slows to near-reverence and Tufiño takes a decidedly more personal approach. A blue neon pentagon, Ace of Pentys, glows before The high priestess, a sculpture of a sky-blue six-eyed goddess framed in baby’s breath. She seems to be watching over Querida Pilar—a video letter to the artist’s grandmother, who raised her and who passed away in 2017 in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria—installed as if protectively hidden from the mania downstairs. In it, Tufiño recites stream-of-consciousness memories that transport her from Berlin to Puerto Rico, where she uses brujeria [witchcraft] to conjure wishes with a coconut and ruminates on a variety of sphinxes. Finally, she recalls a childhood memory of watching the Yves Saint Laurent fashion show during the final of the 1998 FIFA World Cup, an event which used the game and its global stage, mixing haute couture with popular sport to draw a record-setting estimated 2 billion viewers globally, making it a seminal moment in the history of the mass-media business model.

The axiom “if something is free then you are the product” is generally understood to refer to social media but it was coined in 1973 by Richard Serra and Carlotta Schoolman in their video Television Delivers People, which criticized mass media as propaganda for compulsive materialistic consumption. The text that runs across Querida Pilar recites Tufiño’s memories of the fashion show reading “it doesn’t feel that I am remembering,” “time and time again,” and “forever.” The phrases evoke a personal reinterpretation of Serra and Schoolman’s piece: “the product of television, commercial television, is the audience.” Yet the nostalgia with which Tufiño recounts the fashion show suggests the Stockholm syndrome–like sentimental relationship she has as both product and consumer of these media tactics.

Whether as consumer or consumed, all successful transactions are closed by swinging on the hinge of a desire. The violence of web-based transactions is that keyboard-mediated capitalism asserts “a live and lively absence, to which the lack of physical body is not an unfortunate coincidence, but necessary.”1 The purposeful ambiguity of Tufiño’s titular “dancing at the end of the world” invites a slippage of significance. Is she invoking Sisyphean labor or subversive resistance? In either case she seems to remind us to look past disembodied, aestheticized powerlessness and commercialized cuteness to remember that real bodies do not disappear; rather, they bear the hope of reworlding.

Hito Steyerl, “Epistolary Affect and Romance Scams: Letter from an unknown woman,” October, vol. 138 (Fall 2011): 57–69.