What is the blueprint for Black liberation? And where does Afrofuturism fit into it? As if in response to political philosopher Joy James’s charge that Black liberation lacks a workable model, April Bey’s immersive two-room installation offers ways to reimagine Black futurity and governance against the civilizing agenda of European humanism and the afterlife of colonial dependence.1 At the magenta-lit entrance, dubbed The Portal Room, I’m greeted by an effervescent ecology of live plants. On opposing walls, framing the room like clasped hands, are two time-lapse videos—Julia and Namibia (all works 2021)—showing calatheas (also known as prayer-plants) bowing and bending to the revolutionary sounds of Super Mama Djombo. The Guinea-Bissau funk band’s name venerates Mama Djombo, an initiation spirit who presides over an uncleared sacred forest in Cobiana. That Mama Djombo grew in popularity during the anti-colonial struggle in Guinea-Bissau underscores an idea that varied acts of spirituality—from song to ecological conservation—are central to emancipated Black futures.

Continuing with a sense of sonic spirituality, the next room, titled “The Gilda Region” after Jewelle Gomez’s 1991 speculative novel The Gilda Stories, displays three wall vinyl pieces; two murals composed of high-gloss photographs and faux fur; and eight large paintings and hanging tapestries that are either hand-sewn, digitally woven, or a blend of the two.2 These works weave a queer neo-slave narrative about the people and places that make up the imaginary planet of Atlantica—a fictive land Bey inherited from tales her father told her as a child—and confront real-world anti-Blackness by venturing into what Gomez describes as “some mythical future as if the wild west existed in the stars.”3

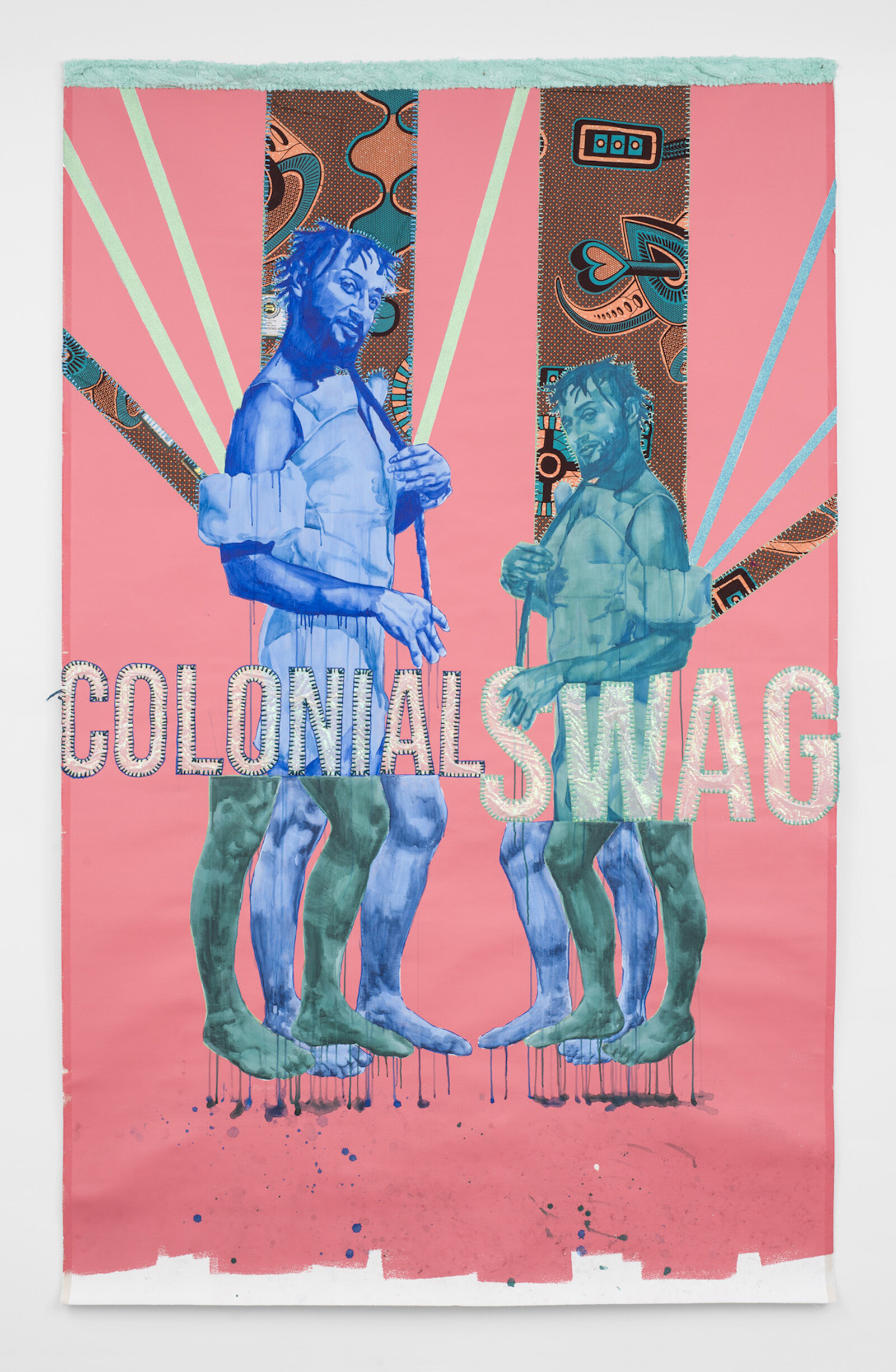

This Old West topography emerges in And My Flames Stay Till You Get Out My Way, a three-panel painting displaying Britt Brat and Pinky from the Maryland-based, all-Black rodeo team Cowgirls of Color. Dressed alike, these twinned figures perch on a magenta sequined fence that pops against a sundrenched, yellow backdrop. The adjacent tapestry, DUNE, represents arid climes which directly reference the planet Arrakis in Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel, as well as actual desertscapes in Namibia. A figure of the bikini-clad actor Astra Marie Varnado occupies the center of the tapestry, while the cropped likeness of fellow fat liberation activist JerVae dots either side. This mirroring motif recurs in Enjoyment, a large, curtain-raiser painting that features Ghanaian-Romanian musician Wanlov the Kubolor. Outfitted in a baby doll dress, the musician’s coquettish poise evokes a queer approach to sovereignty: two smiling watercolor figures stand facing one another, their appendages doubled and dripping. Hand sewn across their waists (and the width of the tapestry) are the bold words “Colonial Swag.” The art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson has connected certain Black craft practices with “flash,” which she defines as a “register of Black American life [and] style” that pushes “past the perimeters of respectability.”4 Dispensing with drab, colonial ways of worlding, Bey adopts across Atlantica a bright, flashy aesthetic—on par with the syncretic Junkanoo parade and costumes—where hybrid textile techniques such as stitching, textual narrations, and photographic patchwork become tools for cartography and representation.

While Afrofuturist utopias (maps) like Bey’s Atlantica provide a semblance of psychic emancipation from white supremacy, the people and places that populate such imaginaries still ground the viewer in an anti-Black present (the unrelenting territory).5 Bey remains wary of confusing map with territory. We gather this from I Got a BackUp Plan to the BackUp Plan to BackUp My BackUp Plan, a scale model of her exhibition propped atop a plinth nestled in the back of “The Gilda Room.” Even the model slyly shows up in the maquette—a kind of mimetic mirroring meets infinite regress, recalling Ernst Bloch’s suggestion that the making of a utopia resides in “escapism and intensification of small things.”6 Elsewhere, Bloch argues that “strangely familiar pictures may appear to us as mirrors of the earth in which we see our future.”7 If we regard Bey’s exhibition alongside its scale model, the familiar and the strange appear at varying intensities that convey not just a fulfilment of the utopia, but a residue of what remains unmet in the here and now.8 Herein lies the tension in Black liberation: what to do with the constraints tethering, for better or worse, the picturesque subject (Black psychic emancipation) and depicted object (Blackness as always already alien, outside the genre of Western humanity).

Against this backdrop, what, then, do we make of Atlantica—Bey’s blueprint for Black imaginary world-making? That we know Atlantica is fictive and utopian with a satirical bent suggests there’s no chicanery here. Bey levels with us on multiple fronts, but two are particularly important: an Afrofuturist tale can be a manual for invention; and utopian models would do well to entertain the possibility that something’s missing.

“Joy James: The Architects of Abolitionism,” YouTube, Brown University (May 6, 2019): https://youtu.be/z9rvRsWKDx0.

I’m thinking here with cultural theorist Marcia Alesan Dawkins’s writings on sonic spirituality as “engaging with something beyond the world around us while grappling with the personas and situations into which we’re immersed.” Marcia Alesan Dawkins, “Sonic Spirituality: Meditations on Eminem’s ‘Beautiful’ and ‘My Darling’” in Sounding Out! (June 24, 2013): https://soundstudiesblog.com/2013/06/24/sonic-spirituality-meditations-on-eminems-beautiful-and-my-darling.

Jewelle Gomez, The Gilda Stories: A Novel (Ithaca, NY: Firebrand Books, 1991), 220.

Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray: Art and Textile Politics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2017), 56.

Drawing on the work of Sylvia Wynter, I’m thinking of speculative storytelling as a kind of “utopian mode of thought” operating outside of coerced rationality. At the same time, Wynter cautions that utopias—like the Black Aesthetics and Arts Movement—can easily get usurped, reinvented, and reterritorialized into the existing order of truth. See Sylvia Wynter, “On How We Mistook the Map for the Territory and Reimprisoned Ourselves in Our Unbearable Wrongness of Being, of Désêtre: Black Studies toward the Human Project,” in Not Only the Master’s Tools: African American Studies in Theory and Practice, ed. Lewis Gordon and Jane Anna Gordon (New York: Paradigm Press, 2006), 107-169.

Ernst Bloch, The Utopian Function of Art and Literature: Selected Essays, trans. Jack Zipes and Frank Mecklenburg (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988), 101. Bey’s recursive model also takes after the echolalic notebook that shows up throughout Samuel R. Delany’s sci-fi novel Dahlgren (New York: Bantam Books, 1975).

Ibid., 102.

This idea of “residue” draws on a conversation between Ernst Bloch, Theodor W. Adorno, and Horst Krüger. Here’s Bloch: “there is a residue. There is a great deal that is not fulfilled and made banal through the fulfillment … So, the fulfillment is not yet real or imaginable or postulatable without residue.” Ibid., 2.