In the wake of the events of May 1968, German Minimalist Charlotte Posenenske wrote in Art International that “it is difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems.”1,” Art International no. 5 (May 1968), n.p.] Posenenske’s “‘Statement’ [Manifesto],” which initially meant to examine ownership and the reproducibility of her artworks, publicly announced the artist’s dismissal of the art world. Having retrained as a sociologist, Posenenske dedicated herself to working with labor unions and refused to show her work or visit any exhibitions until her death in 1985.

While gallery-goers shuttled through Berlin to the rhythm of scattered attention and market consumption, Posenenske’s show at Mehdi Chouakri set the tone for this year’s edition of Gallery Weekend Berlin. Selected galleries of all scales and scopes made a concerted effort to take up the conflated legacies of modernism, rationalized systems of language, and the critique of whiplash-paced figurations of the modern subject.

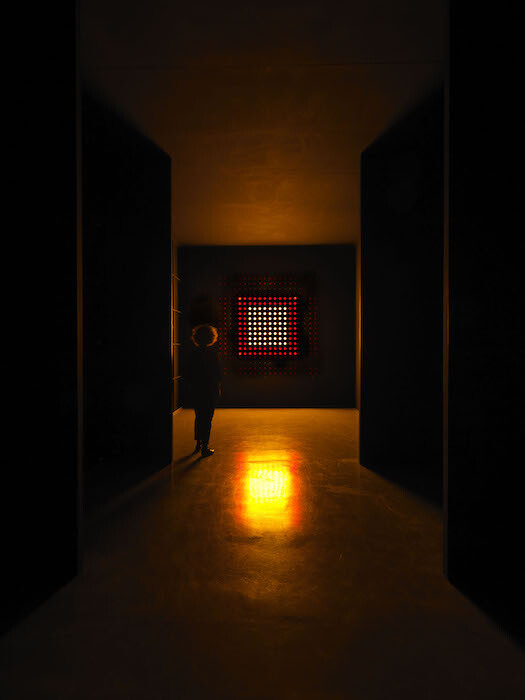

Mehdi Chouakri presents a series of abstract sculptures by Posenenske from 1967, as well as a selection of works on paper from the 1950s in their second space, also in Charlottenburg. Displayed in glass vitrines and hanging on the wall, the latter are sketches of a site-specific commission that combined constructivist shapes and lines with color design. Part of a continued attempt to bridge a dialogue between architecture and the dweller, Series Relief B and C (1967-2017), a range of modular aluminum and sheet-steel sculptures coated in RAL standard tones, appeal to this same constructivist language and concern with primary color. Preceding Posenenske’s 1968 manifesto, the “Series Relief” were created as a set of industrially manufactured elements, which can be reproduced as yet another consumer article.

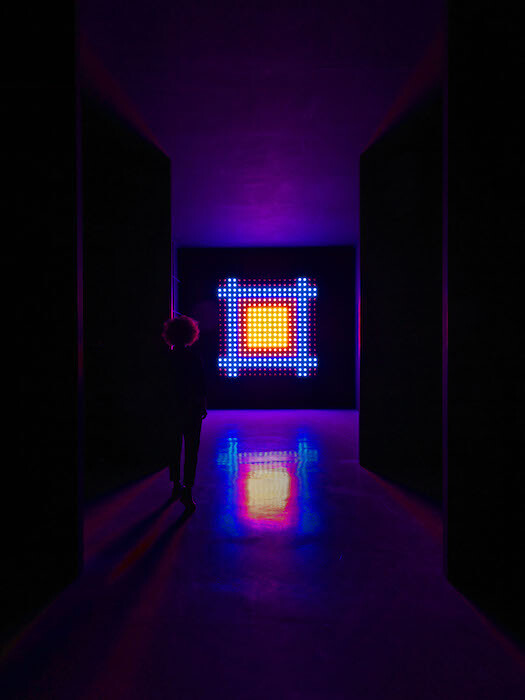

At Galerie Barbara Thumm, Peruvian artist Teresa Burga shows a similar interest in involving the viewer, or “user” in Posenenske’s parlance, in the artistic realization of a redistributive social project. She was part of the Arte Nuevo group—an artist collective formed in 1966 by Luis Arias Vera, Gloria Gómez-Sánchez, and Burga, among others—which critically confronted official institutions in Peru by consolidating a multifarious Peruvian avant-garde. Entitled “Conceptual Installations of the 70s,” the exhibition reunites a series of text-based drawings that seek to expose the constructed and self-referential limitations of linguistic and, more broadly, representational structures. Upon entering the gallery, visitors encounter the series “Borges” (1974-2017), 46 drawings and diagrams conveying the possibility of deconstructing and materializing linguistic data from Jorge Luis Borges’s poems. The installation is accompanied by a sound piece in which Borges’s “La Noche en que en el sur lo velaron” [The Night in which he was mourned in the South] is stripped of words and interpreted in musical notation. Exhibited for the first time in Europe, the installation Obra que desaparece cuando el espectador trata de acercarse (propuesta III) / Work that Disappears when the Viewer tries to Approach it (Proposal III) (1970-2017) staunchly attests to Burga’s interest in the agency of viewers who darken the work as they approach a large quadrangular light panel. Like Posenenske, Burga, a driving force of artistic experimentation in Lima, took professional leave from producing and exhibiting art for over two decades.

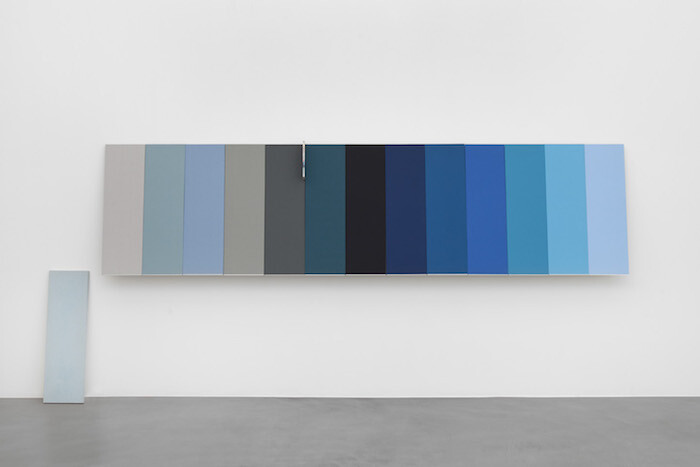

At Arratia Beer “DEMO,” by the Portuguese artist-cum-speculative architectural historian Fernanda Fragateiro, departs from the book Demo: Eine Bildgeschichte des protests in der Bundersrepublik [Demo: A picture of the protests in the German Federal Republic] (1986) to survey and trace the material evidence of a violent protest against increasing public transit prices in Frankfurt in 1974. Within this multilayered installation of found evidence, books—a recurrent leitmotif in her work—appear in several works. They can be seen in the plywood research modules Materials Lab (demo) (2017) and the polished stainless steel sculpture having words (2016), not only as physical volumes and symbolic containers of historical resistance, but also as paratext: an architecture of words and bodies to re-enact the riot. At Galerie Tanja Wagner, modern architecture structures Kapwani Kiwanga’s judicious and elegant presentation of her ongoing research into the social hygiene movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A black line drawn from the 1905 International Congress on Tuberculosis encircles the entire gallery and divides the space for six drywall paintings, a sound installation, and a video projection. While Kiwanga’s camera haptically surveys color coatings on built surfaces in the video work A Primer (2017), three works from the series “Linear Paintings” (2017)—Linear Painting #1 Birren Blue-Greens (RR Donnelley & Sons Chicago, Illinois), Linear Painting #2 Birren Peach-Terracotta (RR Donnelley & Sons Chicago, Illinois), and Linear Painting #6 Birren Yellow-Grey (RR Donnelley & Sons Chicago, Illinois)—further investigate the verticality of therapy and care as proposed by Faber Birren’s 1950s color theory. Kiwanga dissects Birren’s two-tone color palettes, placed in corporations, prisons, and psychiatric asylums for their therapeutic effects, thus evoking the schisms in modern disciplinary architectures and colonial politics.

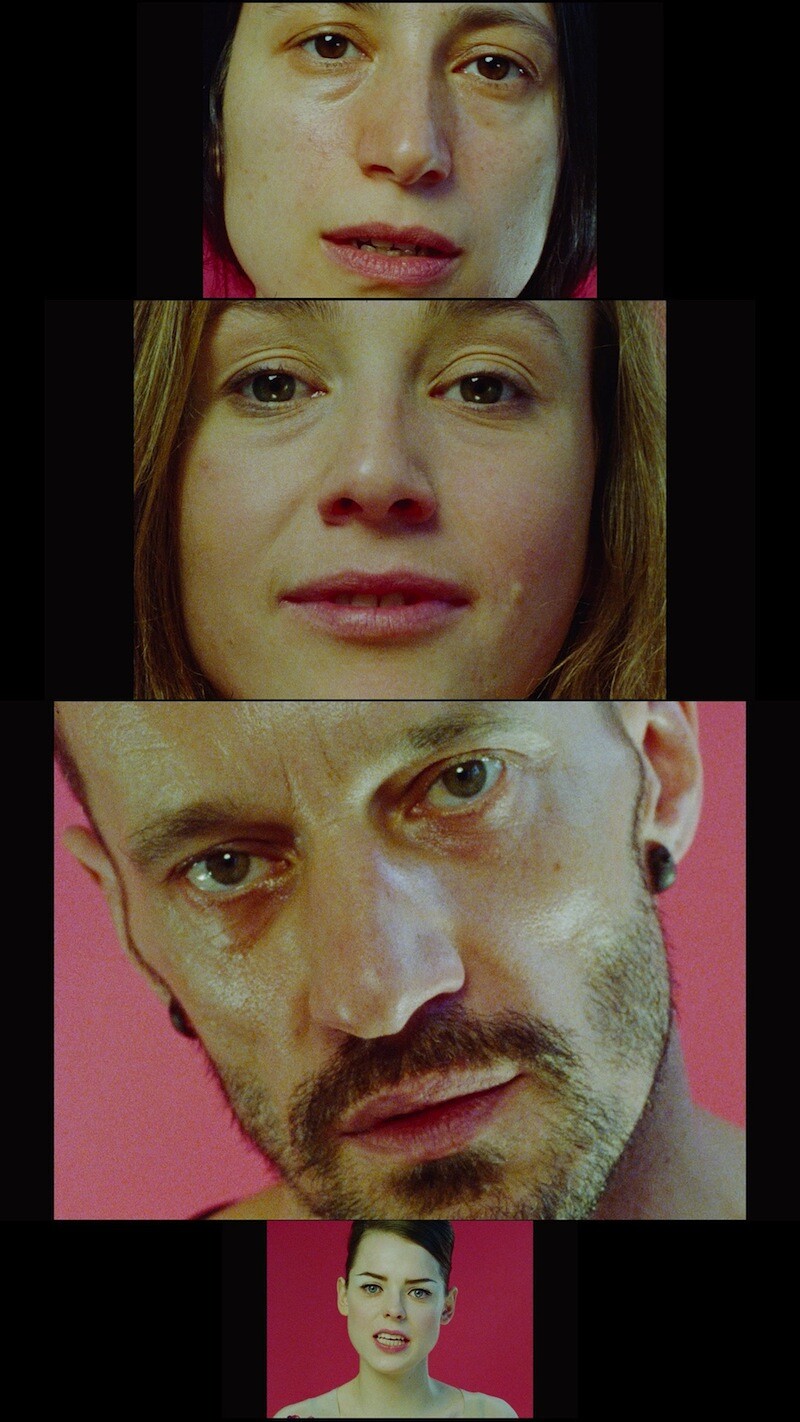

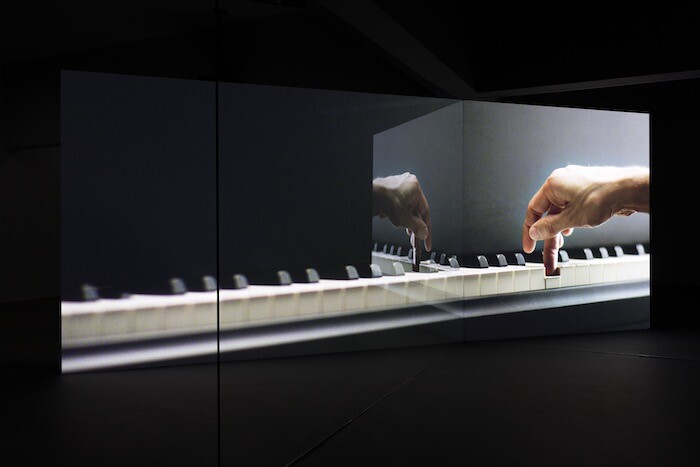

The hegemony of the linguistic reappears in Dara Friedman’s multi-channel video installation Dichter [poet] (2017) presented at Supportico Lopez. Sixteen actors adapt Jerzy Grotowski’s voice training techniques to interpret poetry ranging from Charles Bukowski to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. While amplifying the voice and culling the body, Friedman’s large vertical projection opposes narrative regimentation, appearing in an unsynchronized, overlapping cacophony. The appropriation of cut-up narrative fragments and polyphony continues at Esther Schipper, which inaugurated its new space in Schöneberg with Anri Sala’s Take Over (2017), a back-to-back double-channel projection intersected by two glass panels. The video plays with political and cultural history as seen from the perspective of a prodigious yet frustrated pianist. Centered in the main gallery space, the cross-shaped freestanding structure immerses the viewer in a musical universe of refracted piano keys, players, and politics. As the pianist performs “La Marseillaise” (1792) and “L’Internationale” (1888), multiple iterations of his hands allude to a collective history of revolution and reform. The reflected multiplicity sets in resonance a critical and semantic analysis of the standardization and appropriation of the two anthems.

Multiple voices are also at the core of one of the most anticipated exhibitions of the weekend: KOW’s show of Candice Breiz, who will co-represent South Africa with Mohau Modisakeng in the 57th Venice Biennale. Theatricality and re-enactment are ever-present in Breitz’s moving image works, which examine the literal and figurative demands of lending voice as a practice for inhabiting history. In Profile (2017), Breitz employs ten prominent South African artists who might equally have been nominated to represent the country in Venice. Assorted overlays and performative speech acts disrupt the markers of credibility associated with any portrait of gender, class, and race, as each voice states “My name is Candice Breitz.” The first part of the seven-channel video installation Love Story (2016) can be seen on the floor below. Featuring Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore, it is based on the personal narratives of six individuals who fled oppression in their countries. Breitz tests the mechanics of identification by asking Baldwin and Moore to re-enact the narratives of a Syrian refugee, a former child soldier from Angola, a survivor from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a transgender activist from India, a political dissident from Venezuela, and a young atheist from Somalia. By enacting their stories against the backdrop of a TV studio setting, the same that provides a background to the six original interviews (which are shown one floor below), Baldwin and Moore foreground an economy of exceptionalism purported by the hegemonic Western storytelling industry. Beyond offering some personal release in a weekend of split attention, Breitz’s fast-moving and illocutionary editing is fitting to the fragmented response to the global refugee crisis.

As captious artistic positions and micropolitical actions proliferate in the program of the 2017 Gallery Weekend Berlin, one can earnestly imagine that they attempt to converge some of the curatorial concerns behind the upcoming 10th Berlin Biennale, as well as documenta 14 (which presented “The Parliament of Bodies,” its first public program in Kassel on the same weekend). Beyond a few shared doubts about identity politics, multiple forms of subjectivity came into view. “How does a body become public?” seems to be the question posed by various artistic gestures both within and without the weekend’s official program. While critically surveying the political conditions of representation in various sites of institutional control—from modern architecture to the asylum seeker’s interview office—a number of galleries substantiated a position that may have appeased Charlotte Posenenske. They remind us that within this neoliberal market economy, art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems, but may hint towards practices of attunement with a plurality of voices.

Charlotte Posenenske, “‘Statement’ [Manifesto