Even before you enter Tate Modern’s Bruce Nauman retrospective, you are put on edge. Approaching the galleries, you hear a man and woman shout “I hate, you hate, we hate!” from the screens of Good Boy Bad Boy (1985). As you queue at the exhibition’s entrance, Setting a Good Corner (Allegory & Metaphor) (1999), a video of Nauman erecting a wooden fence, assaults you with the nerve-shredding sound of a chainsaw. These sounds are deeply discomforting, but that which makes you uncomfortable is also that which you cannot ignore. Discomfort makes you aware of your own body: the unease caused by screaming, or the grinding of a saw, manifests in the tensing of muscles. Yet discomfort, in never becoming unbearable, induces self-reflection: you remain aware of what unsettles you and why. Attentive, aware of one’s body, reflective: discomfort shares much with how we think we should experience art. Why then does it feel so bad?

Discomfort as a state of awareness, this retrospective reveals, has been one of Nauman’s consistent preoccupations across six decades of work. Much has been made of Nauman’s exploration of media after Conceptual Art; many have traced his influence on later artists. Yet Nauman’s achievement lies less in his inventiveness with media than with what he has used it to bring to light: discomfort as a distinct mode of relating to art, one akin to the “reception in distraction” Walter Benjamin saw produced by cinema, or the “absorption” Michael Fried saw elicited by modernist painting and sculpture. For such theorists, naming these states was a way to track how art shapes our capacities of perception. Nauman’s work shows how much discomfort can reveal about who we are and what we want, even if we might be reluctant to admit it.

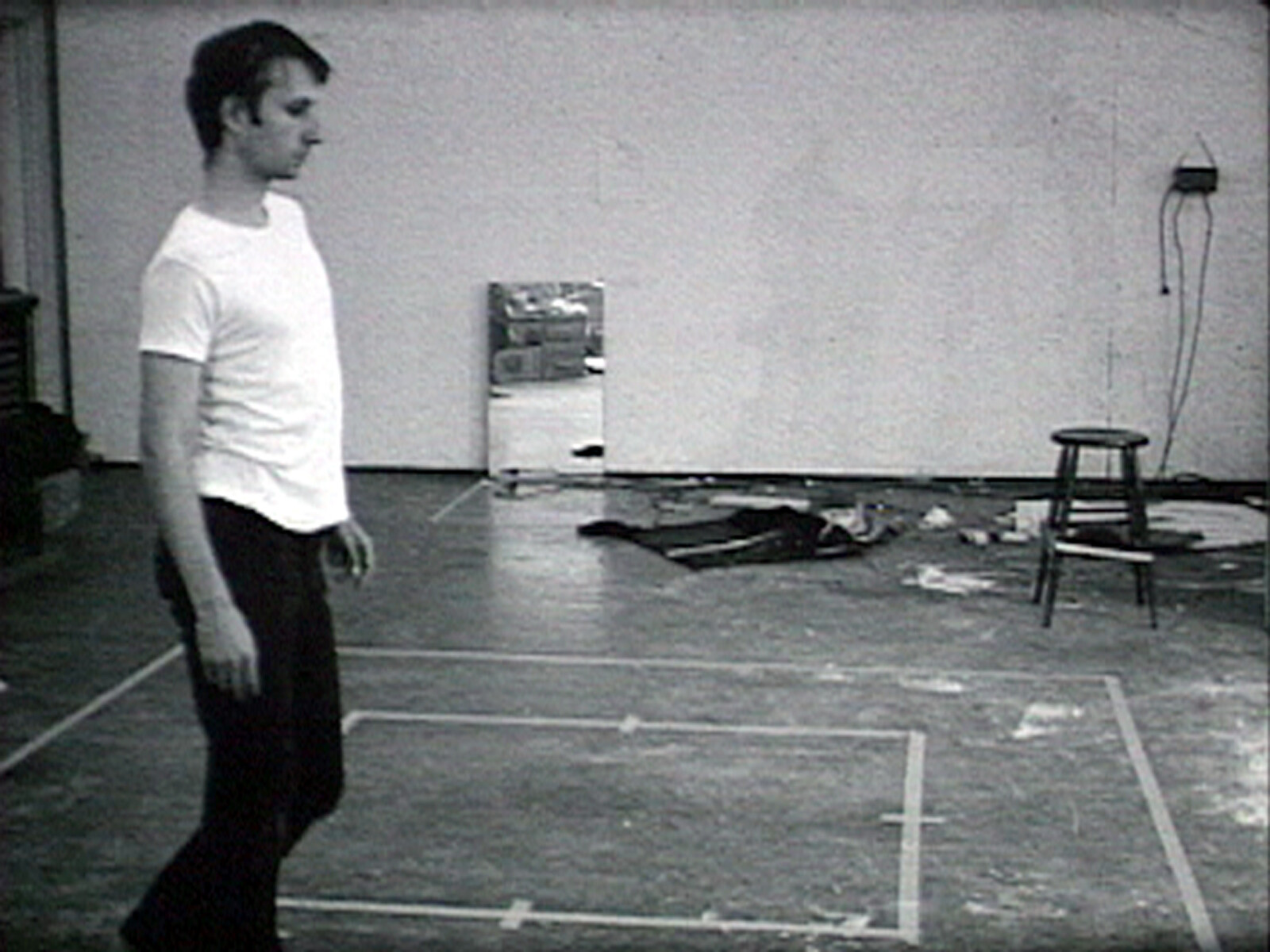

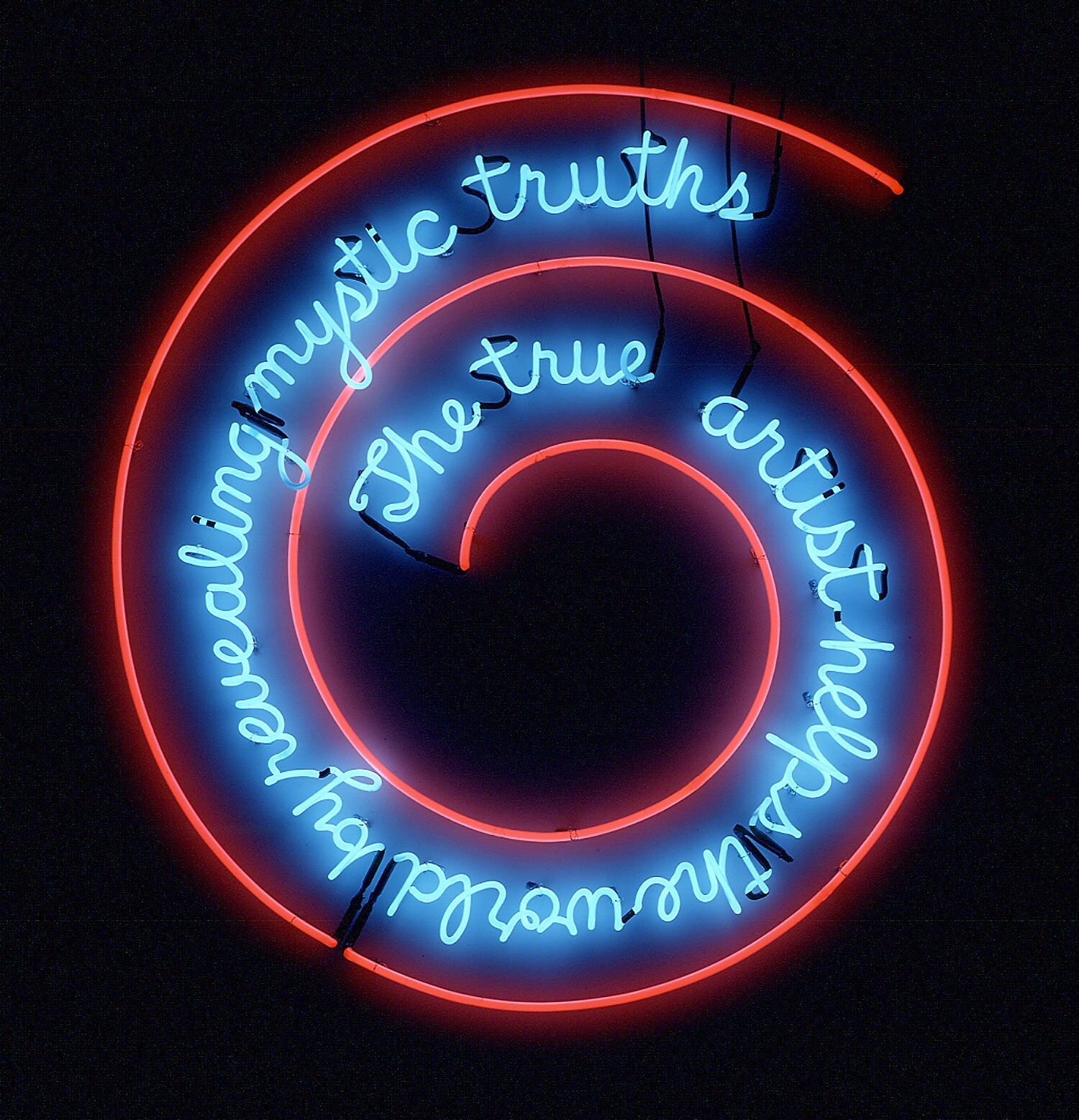

Inside the exhibition, a gentler introduction into this world of discomfort is provided by MAPPING THE STUDIO II with color shift, flip, flop, & flip/flop (Fat Chance John Cage) (2001), an installation in which seven recordings of Nauman’s studio, each lasting five hours, are projected onto four walls of a gallery. You have to strain—either by constantly turning around, or staying for hours—to catch the moments when Nauman himself flits by. The room reveals a concern with discomfort in art’s production as well as its consumption; a line of inquiry which, as the next room shows, began with his earliest work. In the video Wall-Floor Positions (1968) the artist holds poses until he falls over; in Bouncing in the Corner, No. 1 (1968), he endures dull repetitive pain. In Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around The Perimeter of a Square (1967–68), slow walking produces a sashay of the hips that appears frequently in Nauman’s later work. This walk elicits the unease spelled out by a neon piece in the same room: Run From Fear, Fun From Rear (1972). The body of the effeminate man enjoying himself is also that which exposes him to danger.

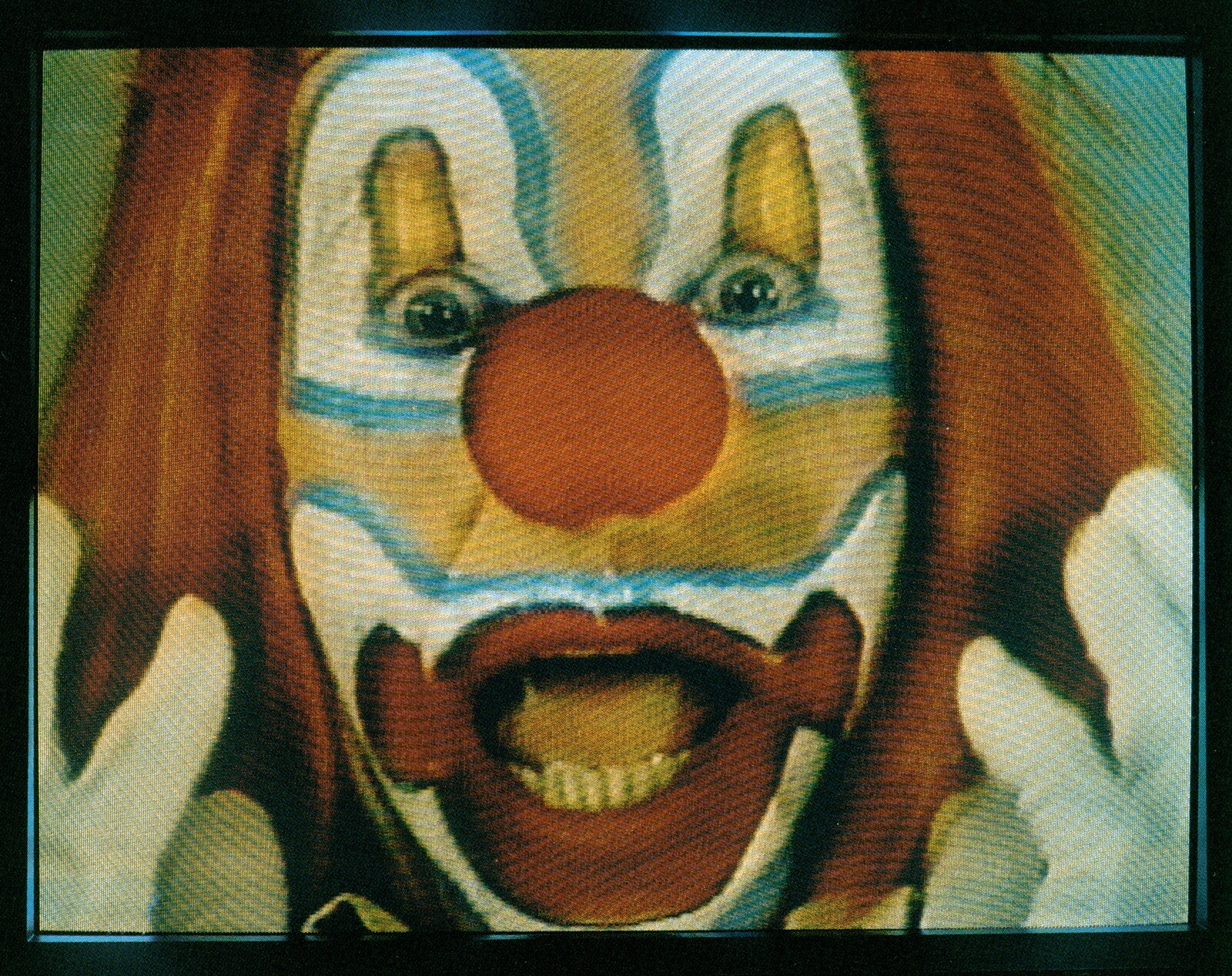

In the following room, the installation Clown Torture (1987) cranks up the sense of disorientation to show us how fear can rarely be separated from fun; that, in fact, it is what makes it possible. Four monitors against a wall show a clown; two scream “No!,” the others shout a rhyme about “Pete and Repeat.” On one video projection, the clown sits on a toilet; on another, he walks through a door and a bucket of water falls on his head. We laugh at a clown because we enjoy his discomfort, when he makes the same mistake over and over again. As Henri Bergson suggested, seeing another body reduced to such mechanic repetition is the source of all comedy. Yet this room is far from funny; the screams are disorienting, the clown is too afraid, we see him off duty. This is an installation to make us uncomfortable about our love of another’s discomfort.

Double Steel Cage Piece (1974), which dominates the next room, further focuses the lens on our enjoyment of others’ suffering. It consists of two steel cages, placed one inside the other, with just enough space left for Nauman to move between them, at least at the time it was first made. Today, they evoke the cages in which migrant children are held at the US border, the same desert area in which Nauman lives, but this is just one instance of the problem these works raise. Much politically engaged art represents the suffering of others; some, like Christoph Büchel’s installation of a boat in which hundreds of people died at the Venice Biennale in 2019, almost restages it. We are meant to feel discomfort, to goad us into political action. Yet Nauman’s work, here as so often, points to the limits of art’s mobilization of emotion for political efficacy. By inviting the viewer to move through the cage, to consume discomfort in a gallery, it makes us feel discomfort about our complicity with art’s use of discomfort, and discomfort about the conversation becoming about our discomfort, trapping us, like a cage inside a cage, in a spiral of narcissistic bourgeois self-loathing…

And so, like the head turning in the monitors and projections of Anthro/Socio (Rinde Spinning) (1992), we see that discomfort as a state of aesthetic reception is bound up with a world defined by a concern with the individual self (does any Nauman video feature two people interacting?). The spinning heads shout “Feet Me, Eat Me, Anthropology!” and “Help Me, Hurt Me, Sociology!” Can such rational knowledge tell us why we enjoy suffering—our own as well as others’? But it is impossible to use this art to think, so loud and unsettling is the noise produced by the screaming heads.

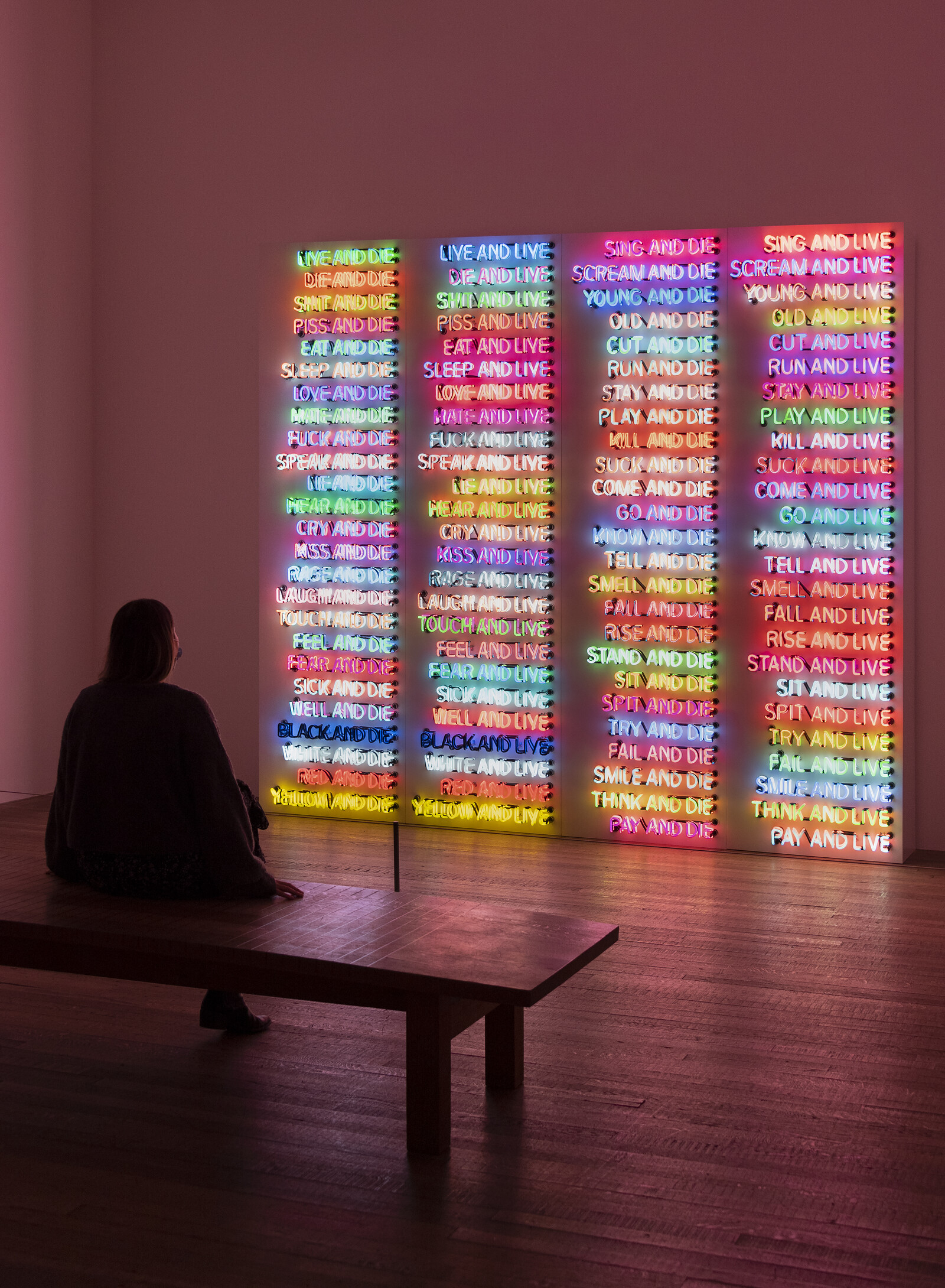

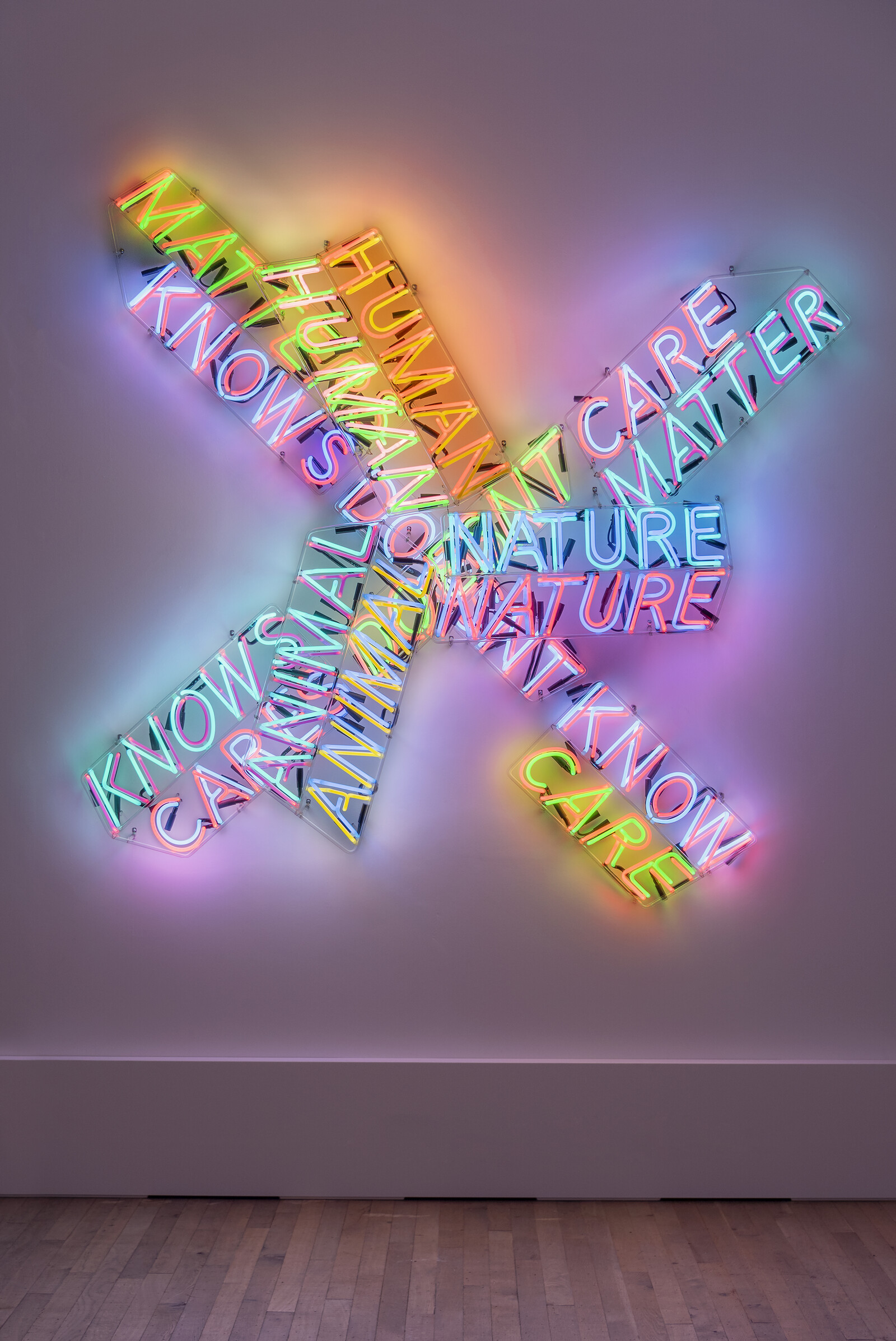

Nauman’s ultimate concern is not with the nature of who we are, but whether, more bleakly, we still care about asking that question. In one room, the neon piece Human Nature/Knows Doesn’t Know (1983/86) displays various permutations of text: “Human / Animal.” “Knows / Doesn’t Know.” “Cares / Doesn’t Care.” While I watched it flash on and off, a girl took a video of a friend as he posed against its pink and violet colours: the perfect TikTok. We are all Nauman’s children now, producers and consumers of infinite loops of video; yet we won’t be for much longer, as any trace of discomfort disappears in the bright glow of posts, shares, and the one emotion social media demands of us: likes.