In an episode of the experimental storytelling podcast Imaginary Advice, host Ross Sutherland reflects on the way cultures over the centuries have exaggerated the meaning of the moon, distorting it from astronomical body into an open, figurative channel. “The moon has a powerful gravitational field,” Sutherland says. “In poetry, the moon draws in concepts, it draws in language. Words just seem to stick to the moon. I maintain that a poet can pretty much compare the moon to anything.”

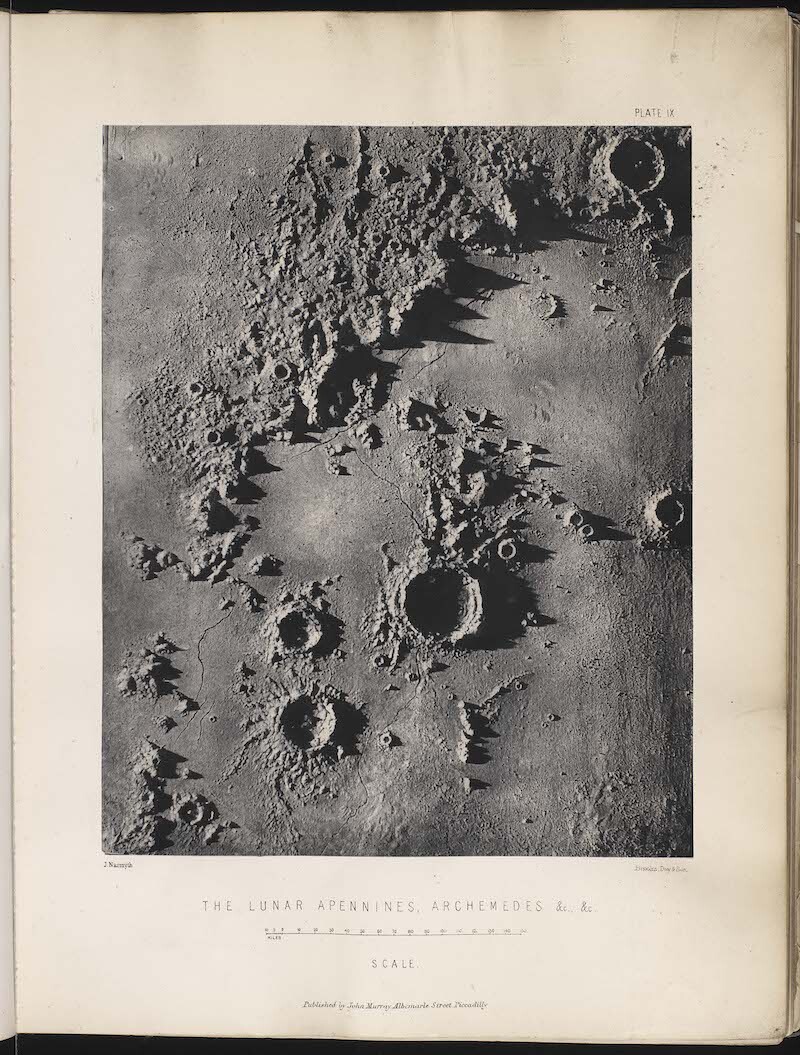

Two recent exhibitions exploring the moon’s magnetic allure are “Jacob’s Ladder” and “Astronomy Victorious,” a two-part display across Ingleby and the University of Edinburgh Main Library. Although the two shows ostensibly survey humanity’s broader relationship with the universe through a combination of contemporary artworks and rare books, the most compelling works share a lunar focus. The unofficial figurehead of both exhibitions is the nineteenth-century Scottish engineer and artist James Nasmyth. Both galleries display plates from Nasmyth’s 1874 book The Moon Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite, which reveal the author’s deep curiosity and ingenuity in pursuit of the moon’s mysteries. Hindered by early photography’s technical limitations, Nasmyth was unable to take close-up photographs of the moon. Instead, he collaborated with astronomer James Carpenter to create and photograph a series of hand-made plaster models of its surface to illustrate his book. Nasmyth had an artist’s eye for arresting visual analogies and these topographic simulations are featured alongside images of a wrinkled hand and a withered apple used to illustrate his theory that the moon’s textured surface resulted from cooling ancient volcanoes.

At Ingleby, Peter Liversidge’s From home – how far the moon has, and is, moving away from the earth since the moon landing, July 20th 1969 (2018) is a perfectly judged inclusion. A fabric measuring tape hangs in the gallery 186.2 centimeters off the ground, marking the distance the moon has travelled away from Earth since Apollo 11 first touched its surface. Liversidge’s measuring tape and accompanying proposal (to extend the tape every year until fully extended, 1,000 years after the moon landings) also makes a thoughtful complement to Katie Paterson’s 2017 work hanging in the entrance hall. Letters cut into sterling silver form the nine words of Paterson’s work, also its title: Ideas - (Objects soaked in moonlight for over one million years). Unlike Liversidge’s proposal, however, Paterson’s piece marks her out as a generator of ideas too big to ever be realizable.

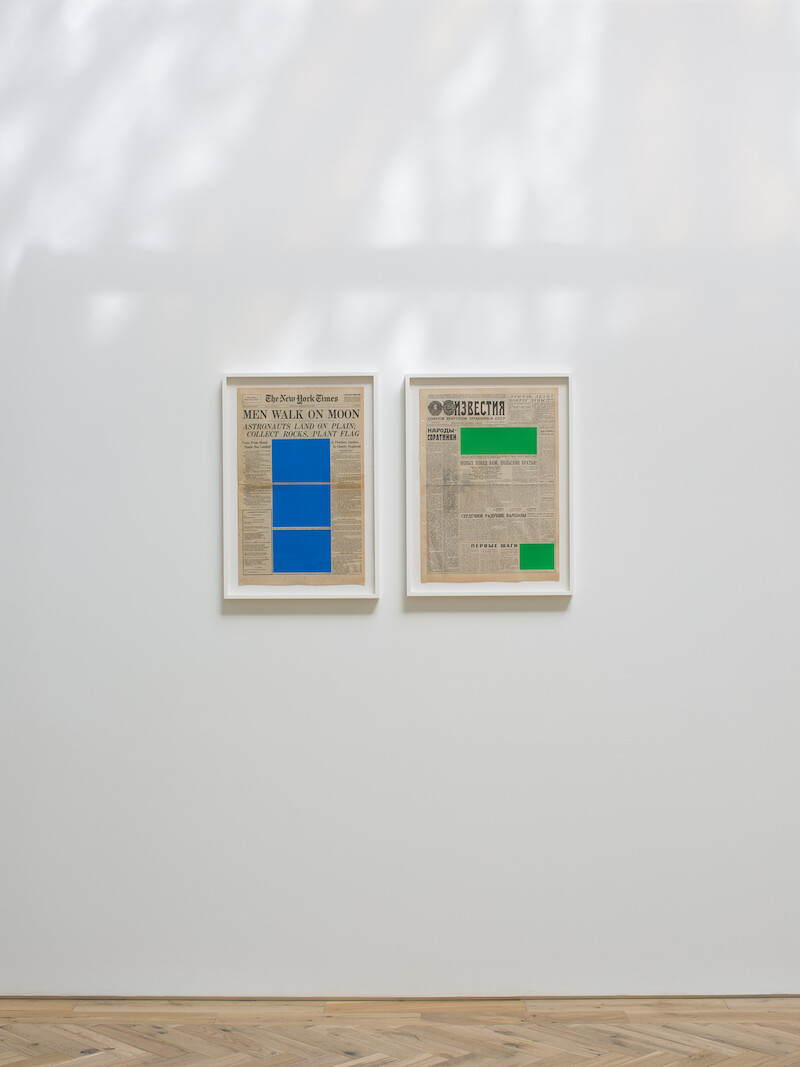

Nearby works by Marine Hugonnier and Georges Méliès perfectly demonstrate the way the moon draws in concepts, however disparate. Hugonnier’s unassuming photograph of a night sky, taken from a found image purchased in a Parisian flea market, is a kind of love poem. Written on the reverse is the phrase “the sky the night we walked on the moon.” This phrase is also the title of her 2013 work and perfectly encapsulates our inexplicable tendency to read romantic symbolism in a mineral-rich ball shining in the dark. By contrast, the anti-imperialist satire of Méliès’s 1902 short film, Le Voyage dans la lune (omnipresent in moon-themed exhibitions, but no less superb for its ubiquity), seems particularly pertinent as techno-optimists continue to imply that escaping to Mars will solve humanity’s Earth-bound problems.

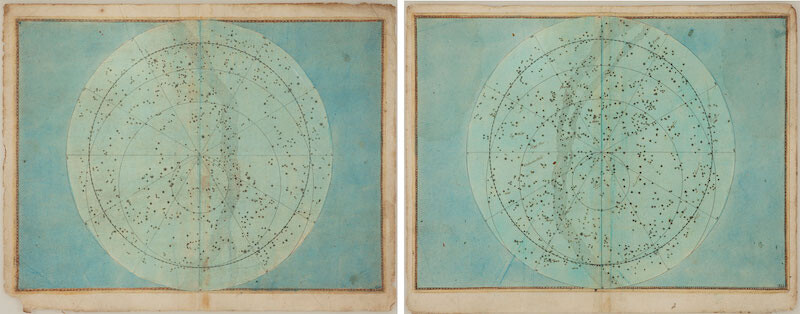

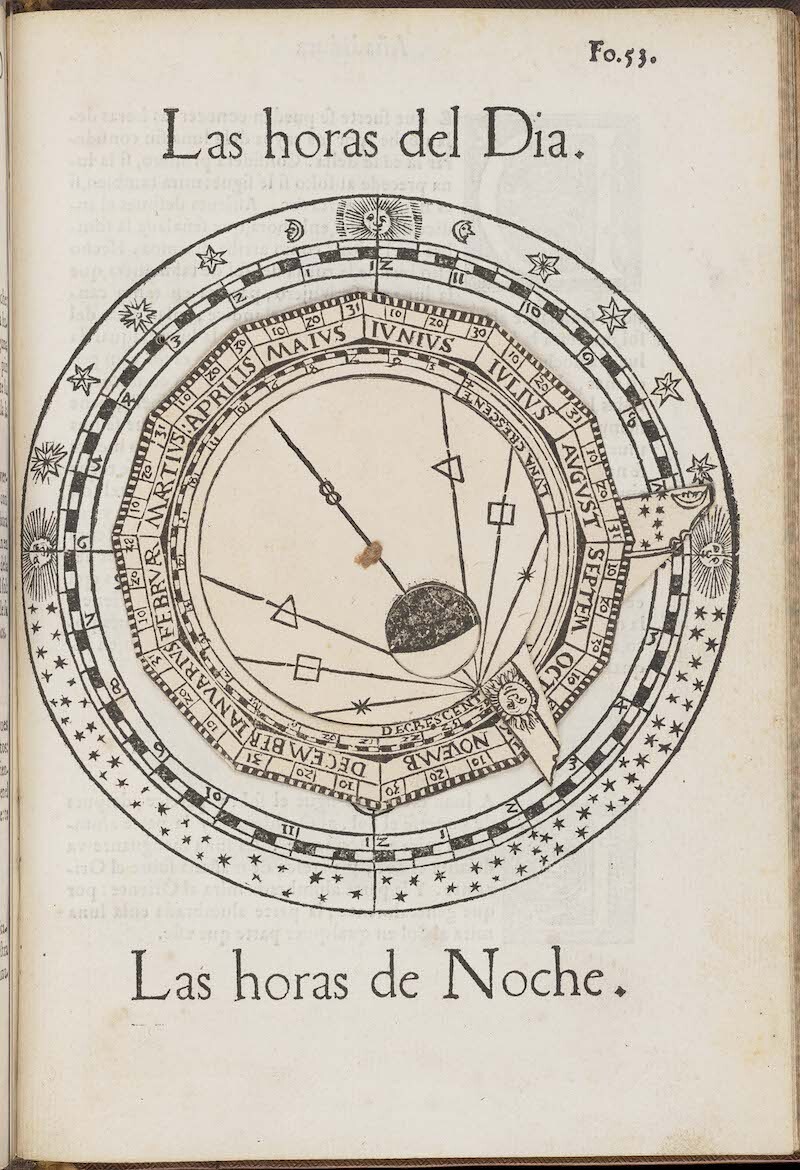

Over at Edinburgh University, where Astronomy has been taught since the institution’s founding in 1583, “Astronomy Victorious” examines the exploration of the universe through historic scientific texts and additional works by artists from Ingleby’s roster. Of the texts, Johann Bode’s monumental celestial atlas, Uranographia, provokes wonder and sympathy in equal measure. For by the time Bode’s detailed folio of 17,240 stars and 2,000 nebulae was published in 1801, it was almost immediately superseded by the profession’s uptake of individual star catalogues. Johannes Hevelius’s modest book, Selenography, or A Description of the Moon (1647) is another remarkable object. The result of Hevelius’s systematic and painstaking observations of each phase of the lunar cycle from November 1643 to April 1645, Selenography was the first published atlas of the moon. Its illustrations are an intriguing combination of topographical mapping and visual shorthand reminiscent of abstract art: large, watery spots represent lakes; double horizontal lines, mountains and valleys; smaller circles are mountain peaks.

The success of “Jacob’s Ladder” and “Astronomy Victorious” derives largely from their drawing together of different forms of representation across disciplines to illuminate the mysteries of the moon and the universe from a variety of angles. The combination of the historic scientific perspectives provided by the university’s rare book collections with the contemporary interpretations of the artists’ works offers a unique opportunity to compare and contrast, and indeed appreciate, the myriad ways in which artists, scientists, and philosophers have sought to better understand natural phenomena through the act of looking and the art of representing. While neither exhibition offers much originality, as a pair they nonetheless compellingly demonstrate why the moon (indeed, the universe) continues to exert such a powerful gravitational pull on human imagination.