Geoffrey Farmer’s lyricism of control is on show at Catriona Jeffries Gallery, although this time with a new suggestion of malignity. Farmer is an exponent of the artistic practice of finding a part of a derelict, languishing image, or two, or more, and through juxtapositions translating these elements into novel, revealing modern utterances. In his 2013 installation “The Surgeon and the Photographer” at London’s Barbican Centre, for instance, he assembled garlands of excised fragments—a part of a statue here, a leaf, a limb, or garment there—to fashion a community of hundreds of tiny, miscegenous personages in whom you sensed love for themselves and each other.

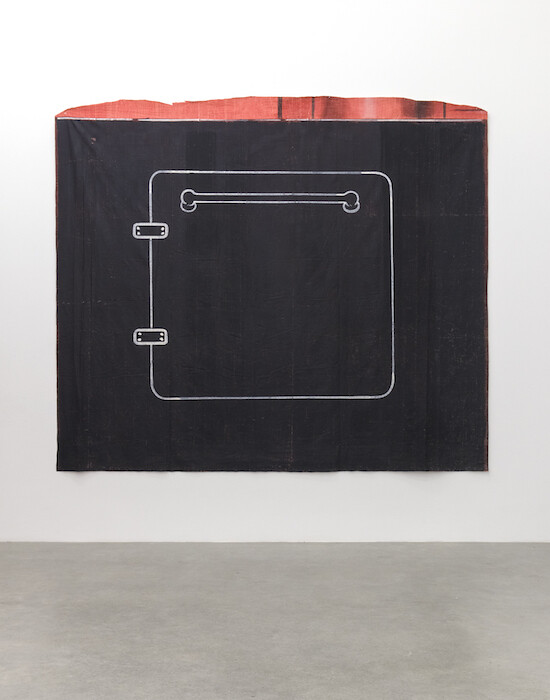

For this new show, he has discovered and rescued an enormous, painted canvas theatrical backdrop. Made by the set design company R.L. Grosh and Sons on Sunset Boulevard in 1939, it depicts a hellish red kitchen. Farmer takes care to make sure that we know its provenance, and also shares in his notes on the exhibition that kitchens have been significant for him: a source of mystery, worry, and danger, of cold coffee and hard crusts, but also consolation. He seems concerned that the momentousness of these things is now receding in his memory. Cut-out elements of this found backdrop constitute much of the material on show here; on the walls, on the floor, turning corners, sometimes pinned in artful display, other times just left to hang, apparently discarded. Parts of the show are of kitchen utensils displayed in ordered rows, analogues of something possibly mendacious. Parts are cupboards and doorways with their trompe l’oeil handles falling into and out of the perspectives they elicit. Parts are just large, crude, unmodulated passages of red wall.

Except they are not crude at all. These fragments of the scenery painter’s craft present nuanced conversations between different pitches of red which allow for the play of space and surface and sentiment. Generous, capable brushmarks and confident overpainting provide depth and allusion to the color. Furled and unfurled so many times, the canvas has become scratched, wrinkled and faded, and this distress adds to its visual sophistication. And, catalyzed by a bold accent in the room—a giant, sky blue broom—these found reds reach out mellifluously to one another, to the many pale gray-greens in the polished concrete floor and to whatever tints can be found in the affordable white of the walls. The effect, which is completely arresting, is to seamlessly coordinate the image of the theater of the fiery backdrop with the gallery’s own theatrical apparatus. The show appears as a beautiful harmonious study, a successful formal composition in its own right. Dressed so, the room represents a monument to bourgeois tastes in the correct arrangement of color and the satisfying distribution of forms and objects. It brings to mind the words that those other theorists of the “found,” Alison and Peter Smithson, used to describe the sensibility of bourgeois space: detailed, expensive, highly controlled, not aggressive, civilized, mind-releasing.1

Farmer is an unfailingly interesting artist, and even in the moment of appreciating this confection, one can’t easily abate suspicions that his introductory rhetoric is a theatrical feint, a veil. These large pieces of canvas prompt thoughts about how Barnett Newman or Mark Rothko or, in one instance, Terry Atkinson, might go about making a painting. Giant brushstrokes and giant brooms suggest Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg. Even in this though, there is a suggestion that allusions to the theater of postwar art are intended only cursorily. The viewer should continue to look for something else, something less concretely apparent. So, theater after interpretative theater is evoked: theaters of unsettled domesticity, of petty punishment, interpreted dreams… and on, and on.

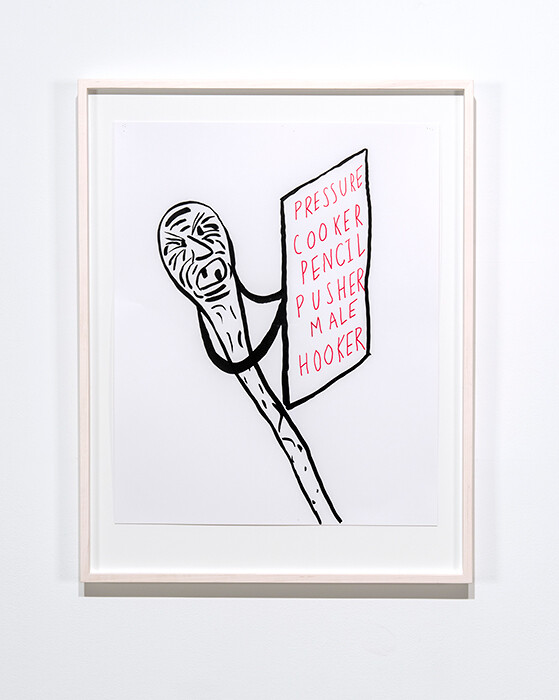

The question of what is required of a viewer at this conjunction of so many theaters, when a proposition is being made about how to recompose a memory, is left open. But, there’s a clue. Interspersing the parts of canvas is a series of framed ink drawings such as PRESSURE, COOKER, PENCIL, PUSHER, MALE, HOOKER and LARD, LOUD, PROUD, STORM, CLOUD (both 2017). In these, a kind of cartoon character is developed, a political figure maybe, perhaps autobiographical. It is a kitchen spoon. Garrulous, crease-featured, hoarse, and splenetic, it has been given broken, blackened teeth and a smoker’s heart. When not asleep or eating, it plays games with a political lexicon and sits barking out complaints in polished, if dubitable rhymes. This cackling spoon, this punning shit-stirrer (shit-disturber, to use the Canadian) speaks not with the technique of Dadaists like Hannah Höch or Richard Huelsenbeck, as one might expect, but one closer to poet Barbara Guest.

Farmer has an accomplished way with words, whether his own or others’, and it seems that there might be, if not exactly a departure from previous work, certainly a shifting of weight; a placing of visual images more at the disposal of literary devices than before. The fiercely poetical incoherence of this spoon’s acid, declamatory character, merrily furious in the face of the shadowy insecurity of the homeland, brings to Farmer’s kitchen something of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s alarming, intelligent malice. In the hilarious and terrifying surreality of our current political theater of bad faith, an oven door as black as the one he gives us here doesn’t pass unnoticed, especially when it seems it might have been put there by some wicked witch.

Alison and Peter Smithson, Without Rhetoric: An Archaeological Aesthetic 1955-1972 (London: Lattimer New Dimensions Limited, 1973), 6.