What was reading life like before the “echo chamber,” the term for the bubble in which one’s own biases are rehearsed and confirmed by other like-minded people? It was not as dominated by single subjects, probably a bit calmer, more demanding in terms of homework and criticality, and with the odd issue you’d want to pass by. The Sharjah Biennial 14—titled “Leaving the Echo Chamber” and put together by Zoe Butt, Omar Kholeif, and Claire Tancons, each of whom has curated their own section—doesn’t have much to do with algorithms, the singularity, or other advances from digital technology. Despite itself, due to the diversity of geographical regions and formal types of work overseen by its curatorial trifecta, this is a biennial with surprises, broad scope, and solid curation.

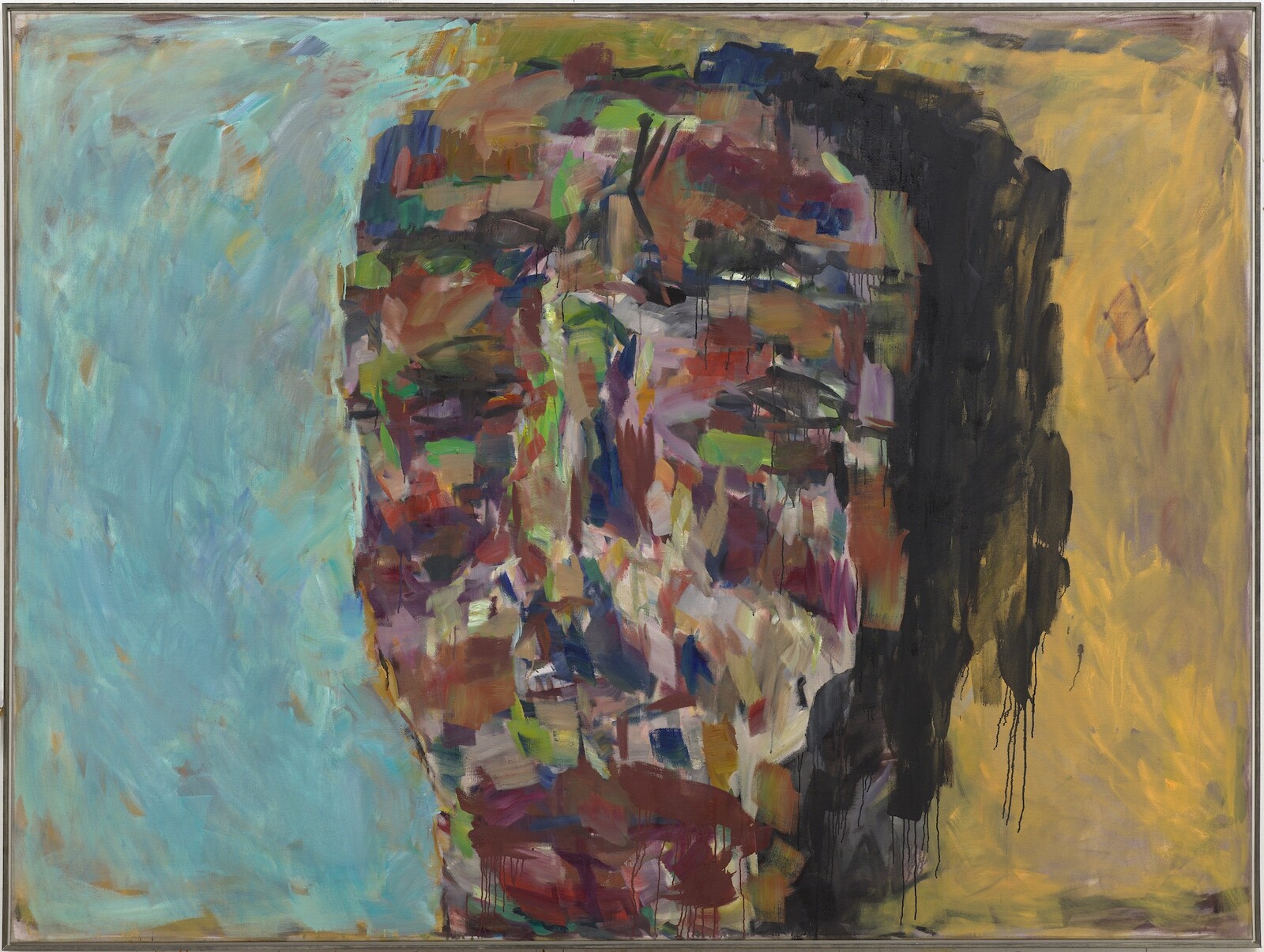

Disembodiment is a key theme throughout Kholeif’s section, “Making New Time,” which is anchored in a strong historical painting show in the Sharjah Art Museum and a more politically driven display at Bait Al Serkal. The painting exhibition opens on the geometric works of Anwar Jalal Shemza, a modernist artist who worked in Lahore, and moves toward formal dissolution: from the Turkish artist Semiha Berksoy’s scratchily rendered figures to the thick brushstrokes of the Syrian modernist Marwan, a portraitist by trade but perhaps a landscape artist at heart, and Bruno Pacheco’s paintings, in which balloon-sellers lift themselves in and out of objective reality. Next door, female bodies painted by Lebanese artist Huguette Caland segue into an installation of her smocks, which hang like stand-ins for the artist herself.

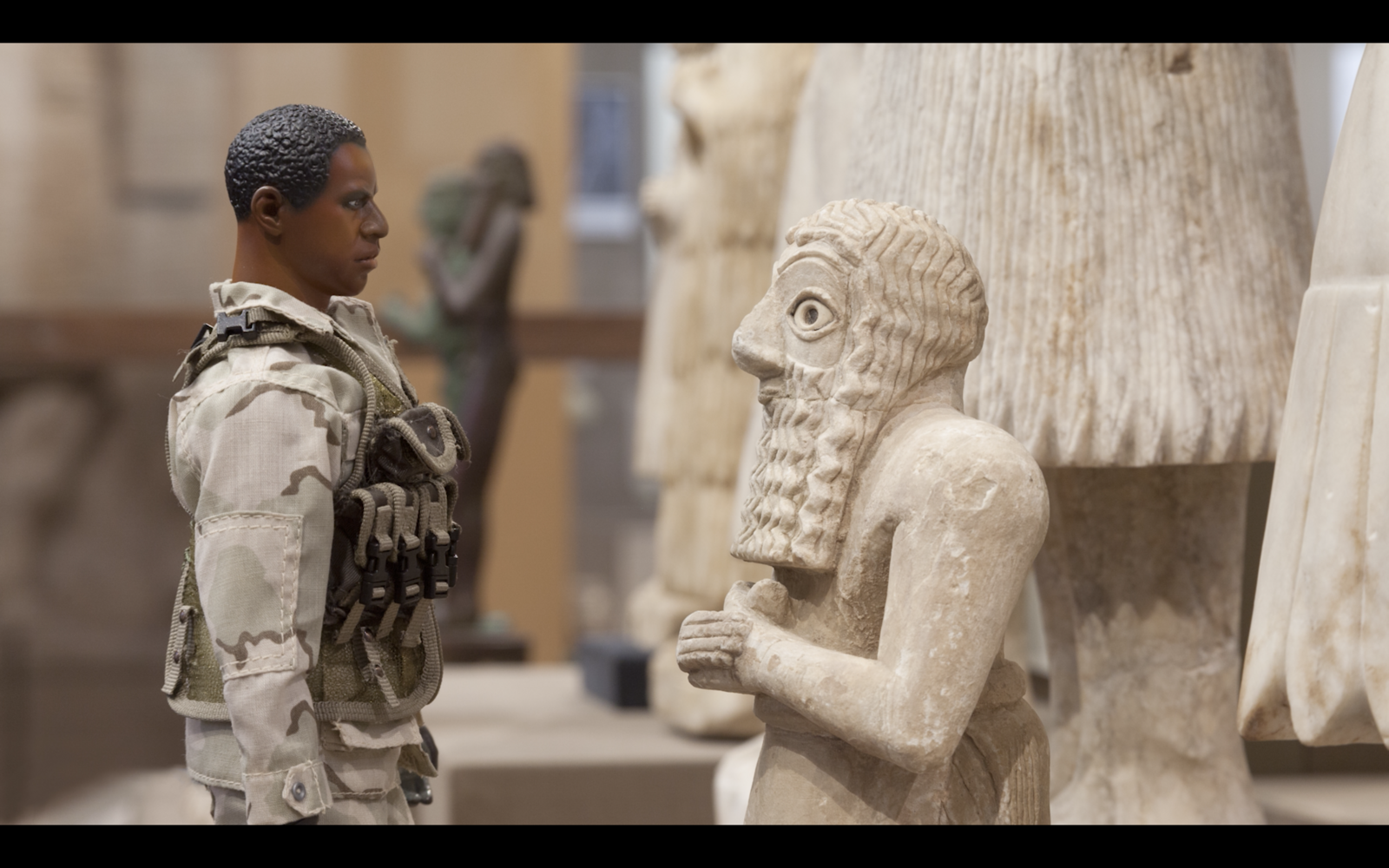

Kholeif’s selection in Bait Al Serkal trades formal relief for technology, and falters somewhat in moments of trendiness. Projected onto the side of the building, Ian Cheng’s trilogy of live simulations “Emissaries” (2015–17) feels out of place, especially displayed opposite Afghani-Pakistani Khadim Ali’s Flowers of Evil (2019), an allegorical mural of winged blue demons that is included in Butt’s program, and is better placed to picture war in this public context. Technological advancement and concomitant anxiety come across more rigorously inside the venue, in works such The Ballad of Special Ops Cody (2017), Michael Rakowitz’s smart video of a black American soldier, played by a doll animated in stop motion, who encounters the cultural heritage of Iraq that he helped destroy. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s video Once Removed (2019) is a portrait of Bassel Abi Chahine, a Lebanese writer and historian who believes himself to be the reincarnation of a fighter who died during the Lebanese Civil War: an acute example of how violence is embodied (and forgotten) generationally. In the Foundation’s courtyard spaces is Armenian-Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian’s Final Flight (2018–19), seven 3D-printed replica skulls of the Northern Bald Ibis, a recently extinct species of birds that migrated between Ethiopia and the ancient Syrian city Palmyra, in a fragile elegy for the Syrian conflict itself.

This biennial sets the subject of migration within a wider geographical context, and, in doing so, mixes it with questions of economic opportunity and exploitation, class, environmental, and emotional costs. It also underlines the global relevance of migration rather than restricting it to the Mediterranean or US-Mexico border crossings: beyond the echo chamber, indeed.

Much of this expansion is due to Butt’s exhibition, “Journey Beyond the Arrow,” which highlights work from Southeast Asia, touching on the legacy of empire and colonialism in the Malay region (including the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore); the politics of indigenous peoples in the Pacific islands; and histories of solidarity movements. As Butt notes, the Malay region’s colonial politics are often overlooked in dominant art circles. The work of the Filipino Third Cinema auteur Kidlat Tahimik, screened during the biennial’s film program, was a rebuke to the longevity of this ignorance. Balikbayan #1: Memories of Overdevelopment, Redux VI (1979–ongoing) is a revisionist historical epic about the Malayan slave Enrique of Malacca, who circumnavigated the world with Ferdinand Magellan. Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project (2016–ongoing), a research presentation by the Malaysian artist Ahmad Fuad Osman, echoes Tahimik’s film in shifting focus from Magellan, who died before completing the circumnavigation historically attributed to him, to Enrique, who made it all the way.

Alongside their respective exhibitions, each curator put together a day of discursive and performance programing for the March Meeting, the annual arts conference organized by the Sharjah Art Foundation that coincided with the biennial’s opening week. In Butt’s case, many of the research-driven projects she commissioned felt more open and less prescriptive there than in their exhibition contexts. Vietnamese director and artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s four-channel video The Specter of Ancestors Becoming (2019), based on research into the shared history of the former French colonies of Senegal and Vietnam, is a case in point. Displayed across four imposing screens with a heavy-handed voiceover, the work itself is loaded; his presentation at the March Meeting, by contrast, left space for the subjects to speak on their own terms. Other works opened themselves up to more nuance. In Mute Grain (2019), a suite of watercolors and a beautiful video, Thao Nguyen Phan addresses Vietnam’s famine in 1945 from the perspective of a child. Improbably, wonderfully, the video makes starvation, abandonment, and shame feel innocent.

Mute Grain was one of 60 new commissions at the biennial, many of which were performances in Tancons’s program, “Look for Me All Around You,” centering on the historical overlaps and synergies between the Americas and the Gulf. In Sabor a lágrimas [Taste of Tears] (2019), the Cuban artist Carlos Martiel scaled a pearl-diving rope in a former date-pressing room; after he left, the rope dangled in chilling shades of the United States’ legacy of slavery. But many of the “site activation” works—a buzzword that papers over the problem of performance in an exhibition context—won’t age so well once their performers have gone. Blida-Joinville (2018–19), a former kindergarten in Kalba, Sharjah, that Mohamed Bourouissa overlaid with a plan view of the Blida-Joinville Hospital in Algeria, where Frantz Fanon worked, will continue to engage viewers. An empty chessboard, once the site of Pataki 1921 (2019), Ulrik López’s performance that draws on elements of Santeria and other spiritual traditions, will not.

The program has a similarly patchy relationship to the Gulf. Isabel Lewis made a raucous performance, Untitled (inwardness, juice, nature) (2019), of circling revved-up cars, after which she headbanged to escalating white noise by the musician duo Hacklander / Hatam. The work presented UAE culture as youthful, larkish, and punk. Other performances felt fly-in, fly-out (pun intended). The collective New Orleans Airlift created The Trans-National (2019), a choreography performed by immigrant workers in the extraordinary setting of an abandoned airplane decorated with photographs and videos contributed by members of the Emirati community. The plane did most of the heavy lifting: from a local context, the multi-nationality of the UAE is among the most obvious things about the country, and doesn’t need to be performed back to it.

Other biennial-size works stared down the spectacular and stopped it in its tracks. The standout work—and the winner of the Sharjah Biennial 14 Prize—was Otobong Nkanga and Emeka Ogboh’s Aging Ruins Dreaming Only to Recall the Hard Chisel from the Past (2019). It tells the story of a palm tree addicted to drinking salt water, that consequently shrivels and dies. The sound unfolds spatially throughout the outdoor courtyard, and culminates in a choral rendition, all parts sung by Nkanga herself, as the tree calls to children to sing for rain. Addiction is no joke here: I returned time and again as if for a hit of beauty. If the introduction of three separate curators heralds yet another minor alteration to the biennial format, a large-scale commission like this one is a reminder of why the exhibition form persists.