It would be impossible to think about London’s first Gallery Weekend in early June outside the context of the slow re-emergence from lockdowns. I know this strange sensation is not unique, but the experience of a public disaster dealt with largely by isolating from society has also marked the way I look at art. Taking stock of my tour of the city, it strikes me that the artworks which affected me most were ones that displayed intimacy, proximity, and all those daily exchanges from which I have felt distant these past sixteen months.

That is not to say that the daily and intimate are not political. At Lisson, “An Infinity of Traces,” a group show curated by Ekow Eshun, focused on the work of UK-based Black artists. It included Alberta Whittle’s video Between a Whisper and a Cry (2019), which explores Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite’s idea of an oceanic worldview in the aftermath of the Middle Passage, and a series of watercolor text drawings by Jade Montserrat (who also has a solo show at Bosse & Baum in South London) that bear heavy, physical messages, like The smell of her still burning hair (2017). When I was trying to focus on Evan Ifekoya’s video Disco Breakdown (2014)—in which the dancing figure describes how they should be doing more political things, like joining a picket line, but all they want to do is dance—my eyes kept wandering to three paintings by Sola Olulode showing couples: close, intimate, and sweet. For days after, I show them on my phone to everyone I meet. Look, this is still happening in the world, I proclaim. And by this I mean touch.

These images of Black joy and intimacy take on extra significance in the context of the continuing Movement for Black Lives. Ifekoya’s insistence on room for dancing and Olulode’s romantic gorgeousness show that space for freedom of creativity and expression matters. I’m reminded of this in front of In It [All], 2021, a small drawing in Martine Syms’s exhibition “SOFT” at Sadie Coles, which shows a couple hugging, with a man visible from the back and a woman holding him, leaning on his shoulder, her eyes closed. The show collects together snippets of daily life in the forms of photographs, drawings, and paintings. Something about the quotidian nature of the images—a kid in the backseat of a car, an apartment full of plants, trips to the beach—feels in line with the artist’s video works. The uniform bright green frames give Syms’s multiple media a coherence reminiscent of the smartphone aesthetic she often employs.

That intimacy is an insistence on living is also palpable in Tosh Basco’s exhibition “Portraits, Still Lifes and Flowers” at Carlos/Ishikawa. Basco’s photographs are small and enclosed: a view from a window, a zoom-in on the petals drooping from a wilting tulip, a portrait in a wooden mirror. Their titles hint at narratives about their creation—the portrait is called Some kind of semblance, the window view onto a lake A stage, the wilting plant Still life ? (all 2021). Basco, known for her performative work as boychild, includes an audio work (Image Description, 2021) in which she reflects on the slippery linguistic relationship between performance and photography: how you would “stage” a photo, how you “frame” an idea. Taken with a smartphone, the photographs are images of piles of printed photos; the phone-camera quality is perceptible, imperfect. There’s a certain casualness to the medium, which allows viewers, seeing just the photos on top of the piles, a small, private snippet of something very personal.1

These window views and flower vases recall the home, so inescapable over these past months. Jessi Reaves’s repurposed furniture sculpture Floral ottoman with trapped table (2017–19) at Herald St also affords a glimpse of the private domain. The glass table landlocked between the two large, shabby, hand-painted ottomans looks like it was meant to be fancy, as in a 1980s vision of a New York City loft, but is here rusty and loose. Still, the huge sculpture looks imposing, taking up the entire middle of the sparsely hung gallery, flanked on the two walls behind and in front of it by Ida Ekblad’s abstract painting THE SAND, THE BEER, THE BUTTS, THE GLASS, THE MATCHES, THE SPIT, THE VOMIT (2018) and Diane Simpson’s enamel and steel wall-based sculpture Boshi (1995), which looks like a hat someone forgot hanging on a hook, only huge.

The shabbiness of the components of Reaves’s sculpture recalled to me the character of Helen in Rosa Aiello’s video Caryatid Encounters (2021) at Arcadia Missa, describing her Berlin apartment to potential renters. She’s nervous and intense; her words come out as both rehearsed and hesitant, as she points to moldy, scrapped-off wallpaper (“original to the 1950s”) and offers visitors some unappealing cookies she baked in the toaster oven (there doesn’t seem to be a stove). Every person who walks into Helen’s place responds to her in ways that mirror her anxiety or neuroses; I feel an uncomfortable empathy that I cannot shake.

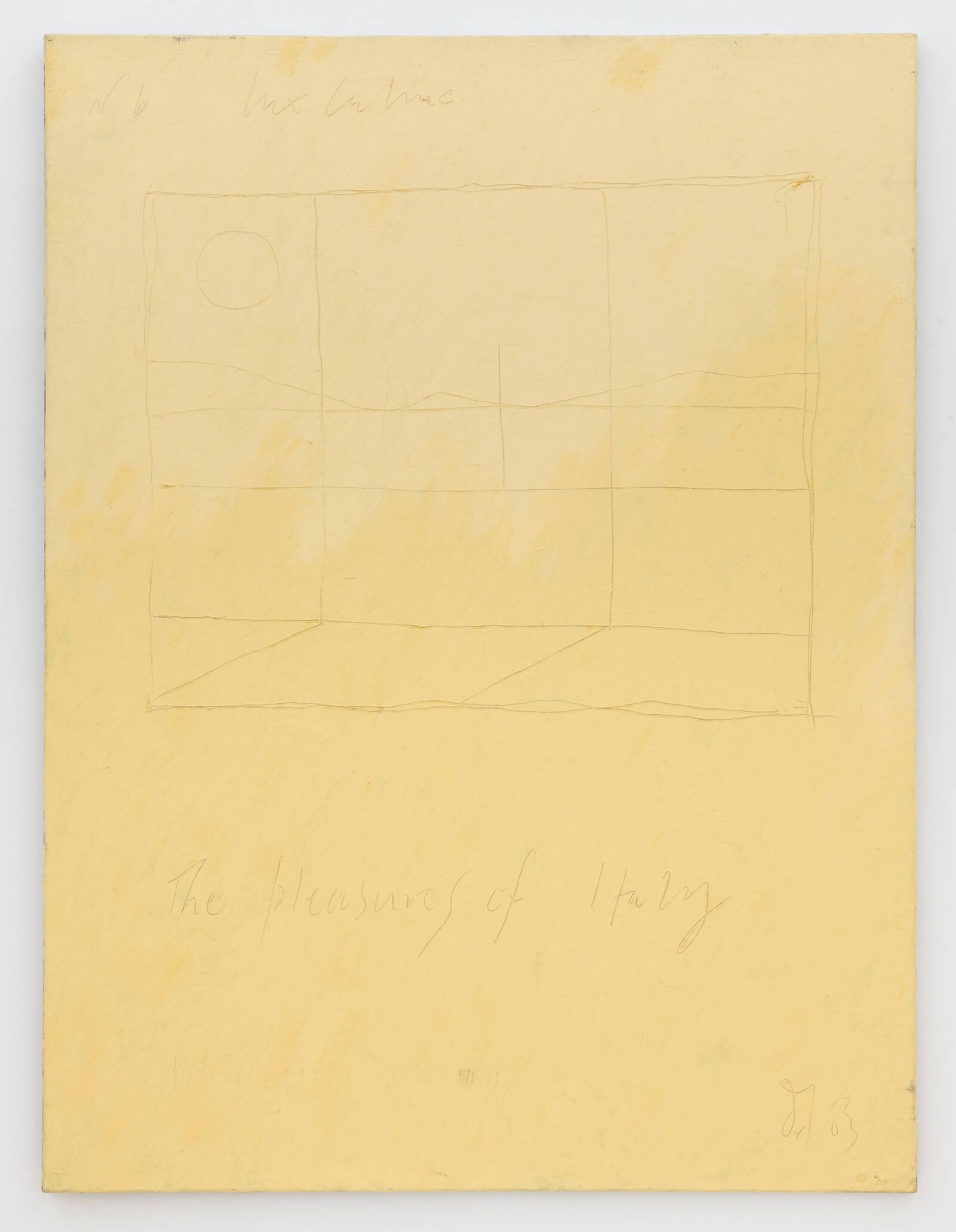

Visiting numerous exhibitions in the same day means that certain visual cues become personal markers of what you’ve seen, a series of connections that feel private. The unfurling wallpaper in Helen’s apartment reminds me of the unstretched canvases by Francis Offman at Herald St’s Bloomsbury gallery. Offman’s abstract paintings, in tones of black, yellow, green, and brown, are hammered directly into the wall. They vary in scale and shape, and yet they all somehow read as landscapes, as if the green could only ever be grass, the browns sand, the blacks a night sky. Or perhaps at a time of narrowed horizons, such landscapes feel like harbingers of a different reality. Seeing Patricia Leite’s paintings at Thomas Dane, the first thought that occurred to me was just how different an image of Brazil they provide—the vividly colored flowers, fauna, and seascapes—in comparison to the Covid-19 crisis imagery that accompanies every report on the country in the news these days. Another loaded sense of landscape is found in “When yellow wishes to ingratiate it becomes gold,” an exhibition of paintings by Derek Jarman at Amanda Wilkinson. Dating from 1982 to ’92, around the time Jarman was diagnosed as HIV positive, the paintings’ relationship to their subjects is restricted but also playful, questioning the world while depicting it. Untitled (Yellow Painting – The Pleasures of Italy) (1983) shows a sketchy geometry where the circle in the top left could be the Italian sun and the diagonal line maybe a horizon at sea or a mountain range. Or maybe I’m just thinking that because of the cursive text underneath the image reading “The pleasures of Italy.”

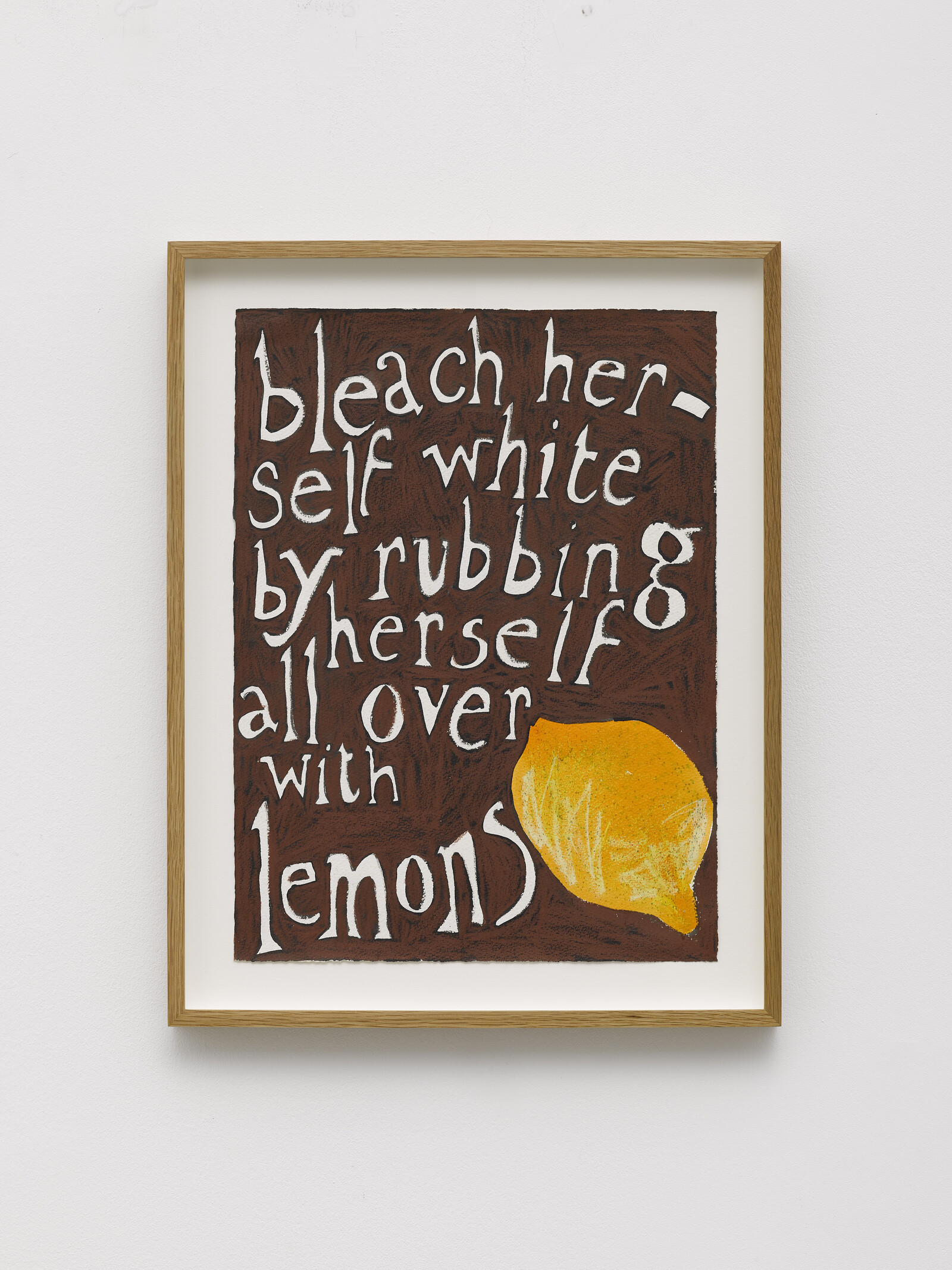

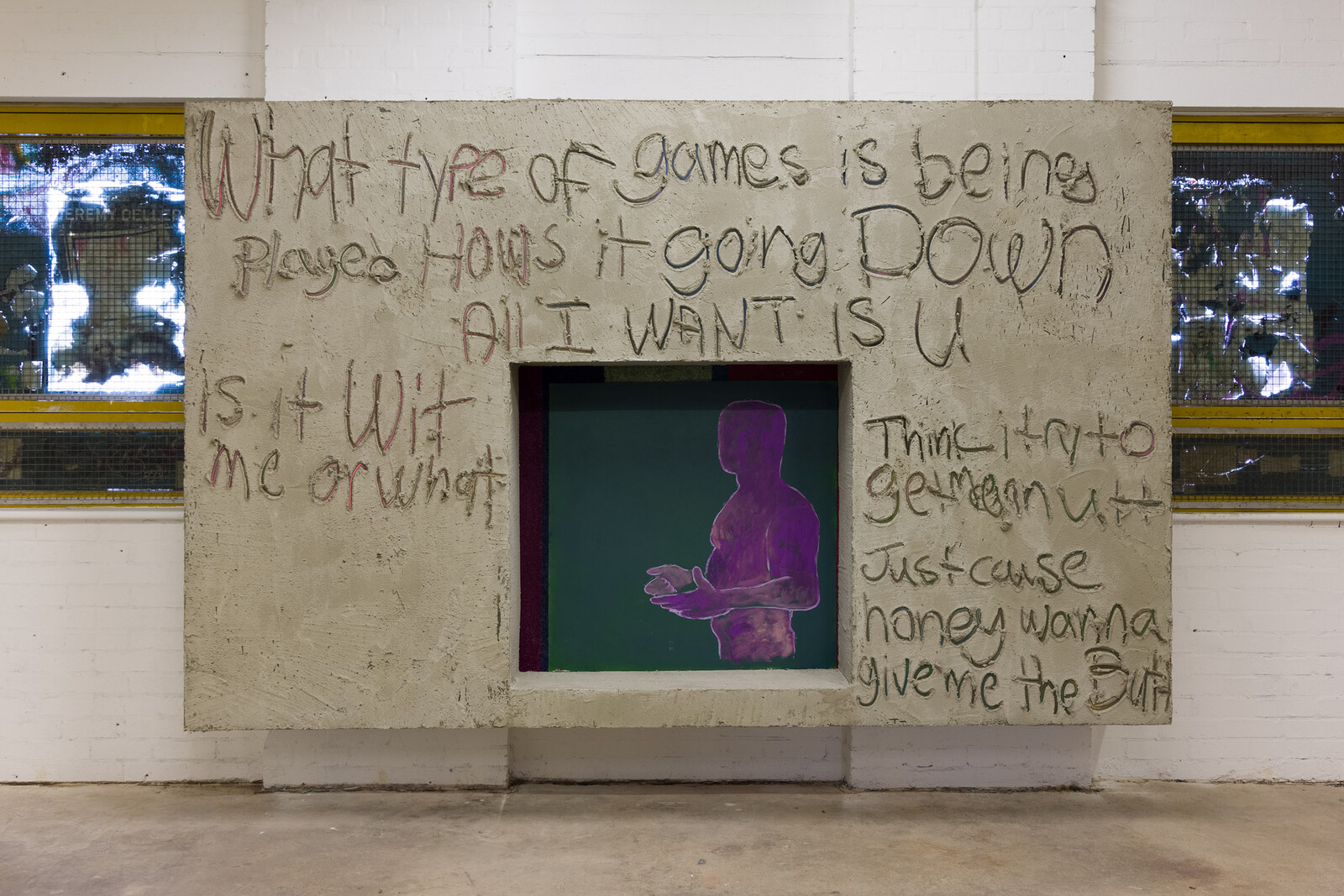

A text-to-painting relationship is also central in Alvaro Barrington’s exhibition “My words will live forever-Fuck my Name” at Emalin. One of two concurrent solo exhibitions by Barrington, at the gallery’s permanent space and another temporary one around the corner, “My words…” is dedicated to musician DMX, who died earlier this year. Portraits of DMX are embedded in painted wooden boxes covered in cement, onto which the artist has carved fragments of DMX lyrics (“all I know is pain,” “is it wit me or what”). Going down (2021), a portrait in acrylic and oil on paper and snippets of carpeting, is painted in green and purple, a gentle and funerary tribute to the late rapper’s love of orchids.

At one gallery, I run into a friend who tells me how he recently went out to dinner, and it all felt so familiar that for a second he thought maybe no one else had been isolating for the past sixteen months. We speculate that all those diners have actually spent the year in that restaurant, ordering rounds of drinks, living in an alternate universe, and laugh, taking comfort in fiction as we try to catch up. It’s hard to make sense of what has happened in this year of crises—the politics and struggle, the home and the intimacy and the intensity and the pain. It’s hard to build a narrative that even begins to describe it. Art helps: a coming-together finally, with other people, in public places, around a shared object on which to reflect. It feels like a way to connect. Also, very real.

For more on Basco’s new work, read her recent conversation with Sophia Al-Maria for art-agenda: https://www.art-agenda.com/features/391075/back-and-forth-maybe-with-some-chatting.