Please consider this a compliment: Camille Blatrix’s solo exhibition at the Kunstverein Braunschweig is so spartan it teeters on the razor’s edge of not enough. Its vibe is expectant and hungry, and it leaves viewers feeling the same. The artworks, too, are cold, hard morsels. Their most prominent quality is want. One might anticipate these conditions from an artist who is known for his expertly machined, mystery objects, but possibly less so from an artist who also claims to make, in the most heartfelt sense, “emotional objects.” I cannot stop thinking about “Somewhere Safer.”

The show’s pervasive self-denial leads to descriptions in the negative. Unlike so many installations with a minimalist edge, “Somewhere Safer” does not recall a temple. There is nothing tranquil about its emptiness. There is nothing sacred about the cardboard boxes sitting on the floor, nor the harsh, flat light from the ceiling. There is nothing that does not deflect a head-on approach to what is presented. Hence, a caveat for what follows: the only recourse is a sideways path to understanding.

I read that Blatrix enjoys romantic comedies, so I am watching Pretty Woman (1990). The film is very charming; it sparks minor insight as I contemplate the temperament of a man who trades mostly in riddles and has a fondness for a meet cute. Perhaps it is the coyness in these plots that is appealing, or the shenanigans linked to miscommunication. Both speculations are applicable. Perhaps the appeal is more fundamental to the human experience. A romcom describes a process of actualization through love, cultivated by an energy between characters that emanates possibility. Their futures are undifferentiated—in jeopardy even—until the moment their fate is sealed in permanent cinematic coupling.

If a fate fulfilled is considered a verdict, and such a verdict forecloses all other potential modes of being, then the open-endedness of “Somewhere Safer” begins to make sense. Its restraint is willfully pre-climactic. All of the artworks date from 2018 and are untitled. This includes those aforementioned boxes—three in total, stacked in an L shape. Hiding behind them is a trademark Blatrix sculpture. Its parts are seamlessly combined and spark numerous mental connections: a ski, a rower’s ergometer, a trap machine, a single-shot firearm. Its muzzle peaks over the edge of the lowest box, and is positioned in line with another, wall-mounted sculpture across the room. The second piece resembles a crossbow, a bird, a flower, a klaxon. It blows air from its nozzle. The two inventions are locked in dialogue on an invisible axis. The arrangement, albeit inscrutable, is mutually beneficial, for whether hunter and hunted or paramours, they never lose (sight of) each other. They are preserved in the tensest, and therefore richest, moment of their becoming, regardless of its nature.

There is safety in the holding pattern, just as there is safety in loving the concept of “love” instead of actually loving another person. Loved love is a sealed cardboard box, throbbing with promise. No disappointments, no pain, no endings. Only anticipation. Always bated breath. As Nele Kaczmarek writes in her curatorial statement, footnoted with a reference to the German sociologist Rainer Paris: “The anticipated future overshadows the present in the constant mode of ‘not yet.’”1 Loving love is loving pure potential.

Lest I be accused of overinterpretation, the exhibition’s ambient soundtrack is “I Will Always Love You” by Whitney Houston (1992), modified to loop only the first two words of the refrain: “And I…” Viewers never get the satisfaction of “…will always love you,” but they are also spared the part about bittersweet memories and crying. She will always be teetering on the razor’s edge of bearing her soul.

The audio emanates from behind a false wall that the artist erected to divide the gallery, closing off one half like a drum. The choice is among his most perplexing: it makes listeners feel like they are hearing Whitney while in utero. Although the room where nobody can go is exactly that, it remains a major component of the exhibition. In its isolation, the room is a container as withdrawn from purpose as Blatrix’s more discrete pieces; paradoxically, it is a space open for anything because of its inaccessibility. For viewers not already familiar with the building, this modification to its layout might go unnoticed and unexplored, considerable though it is. The miscalculation is exacerbated by a reflective gold film applied to the exterior windows—but if the light is just right, and one counterintuitively presses an eye against the glass from the outside, the quarantined space is softly visible.

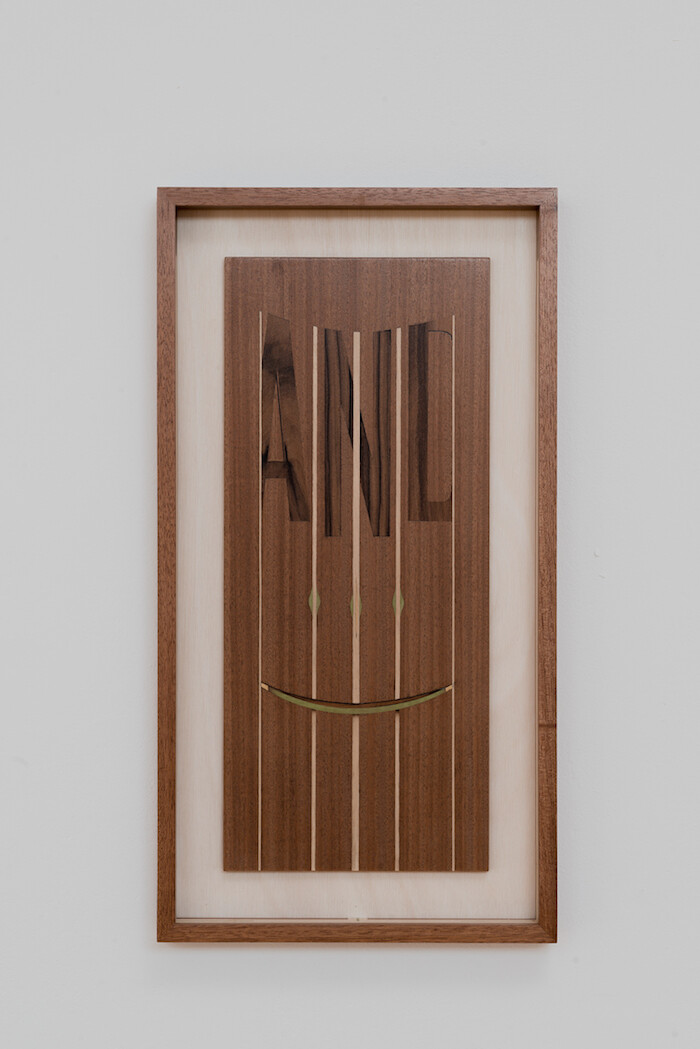

Blatrix’s carpentry skills are apparent in a false vestibule to match the false wall and three wood-inlay hangings that are as tight and complex as the other sculptures. Two remain in the vestibule, but a third hangs in the main hall above the shotgun-ski. The word “AND” is fitted into the surface above a small, green curve. I’m told it represents a smile. There is much possibility in this terse, little world.

Exhibition guide to Camille Blatrix, “Somewhere Safer,” at the Kunstverein Braunschweig, 2018.