The eleven compact paintings in Jennifer J. Lee’s “Wallflowers,” all dating from 2020, hang heavily on the white walls of Chateau Shatto, Los Angeles. Each work is around A4 in size and plays with layers of texture and detail, transferring source images of intricate scenes—stonework, crocodile skins, flowers, and seeds—onto an unforgivingly wide-woven jute. The slime-aged arches of Abbey, the blood-orange marble of Elevator, the baked psychedelia of Wallpaper—the unprimed material dims Lee’s colors as if with time.

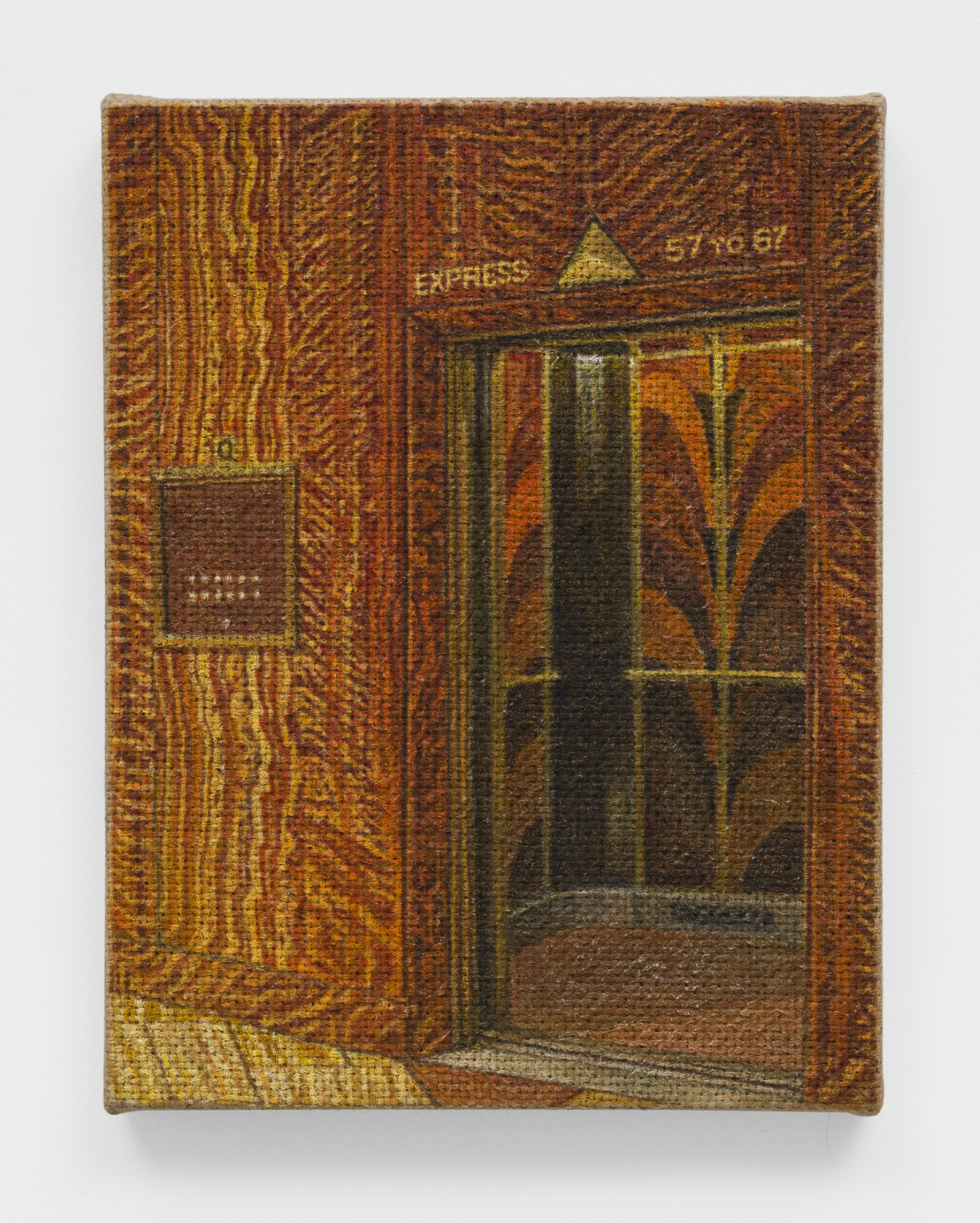

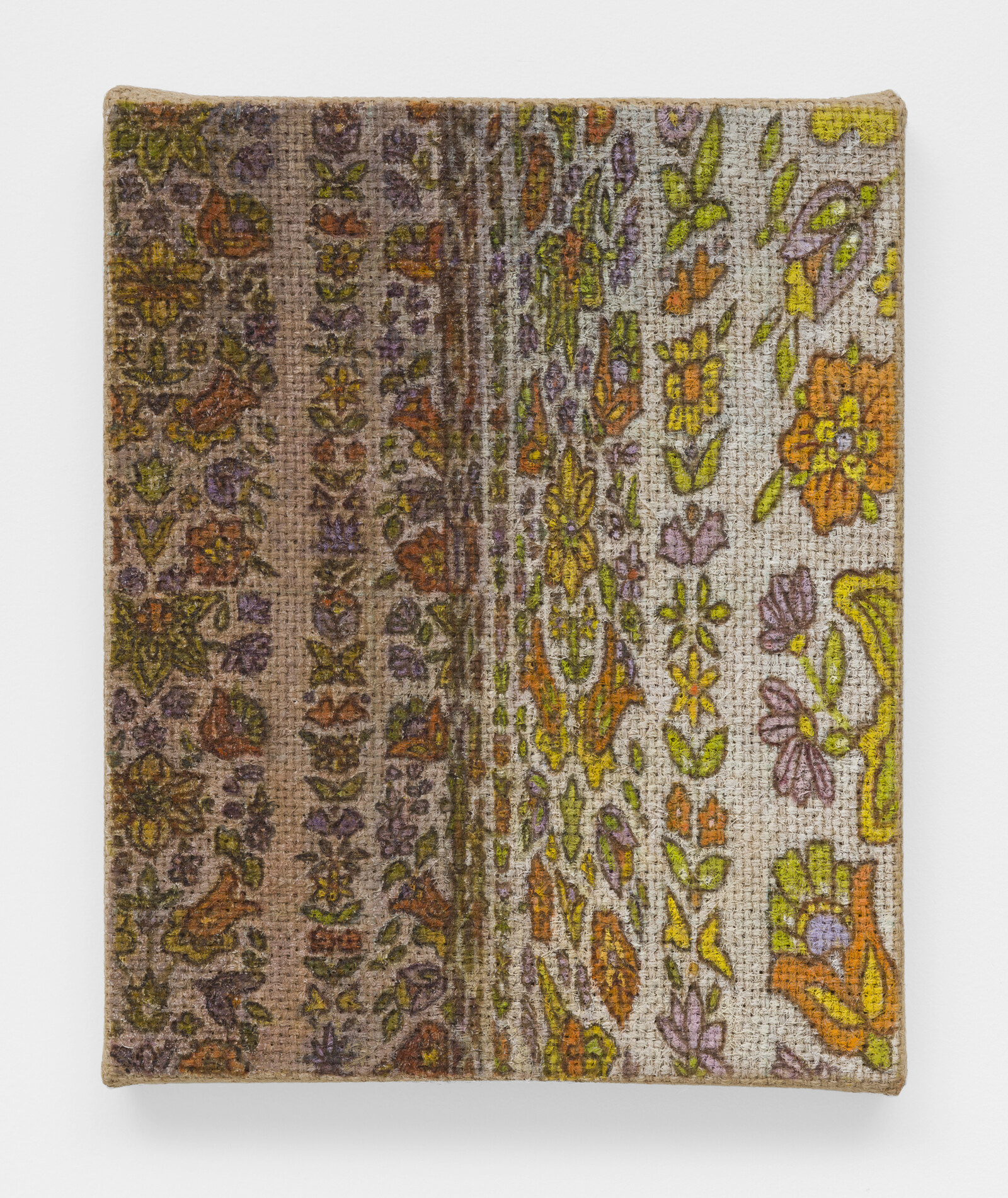

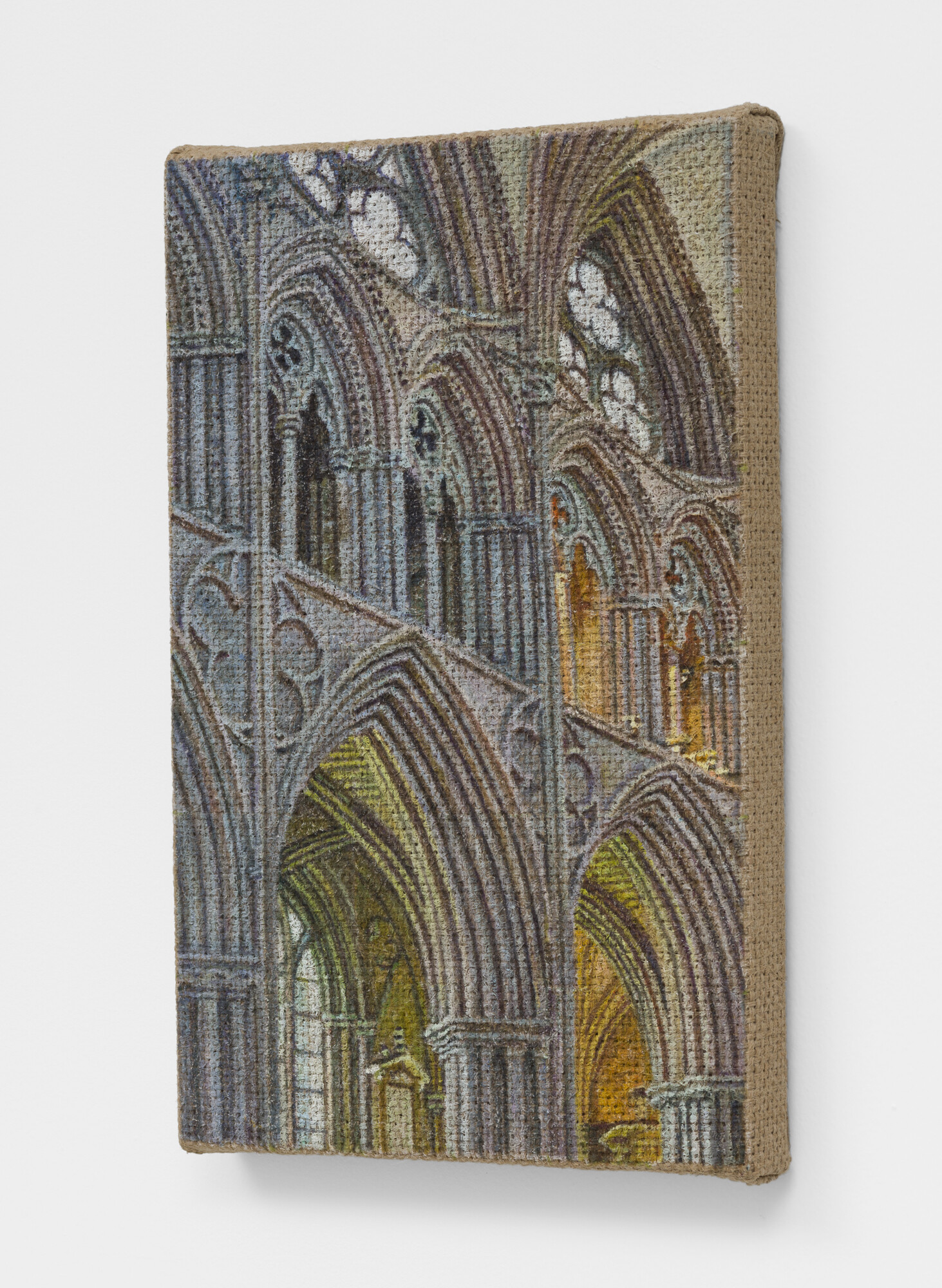

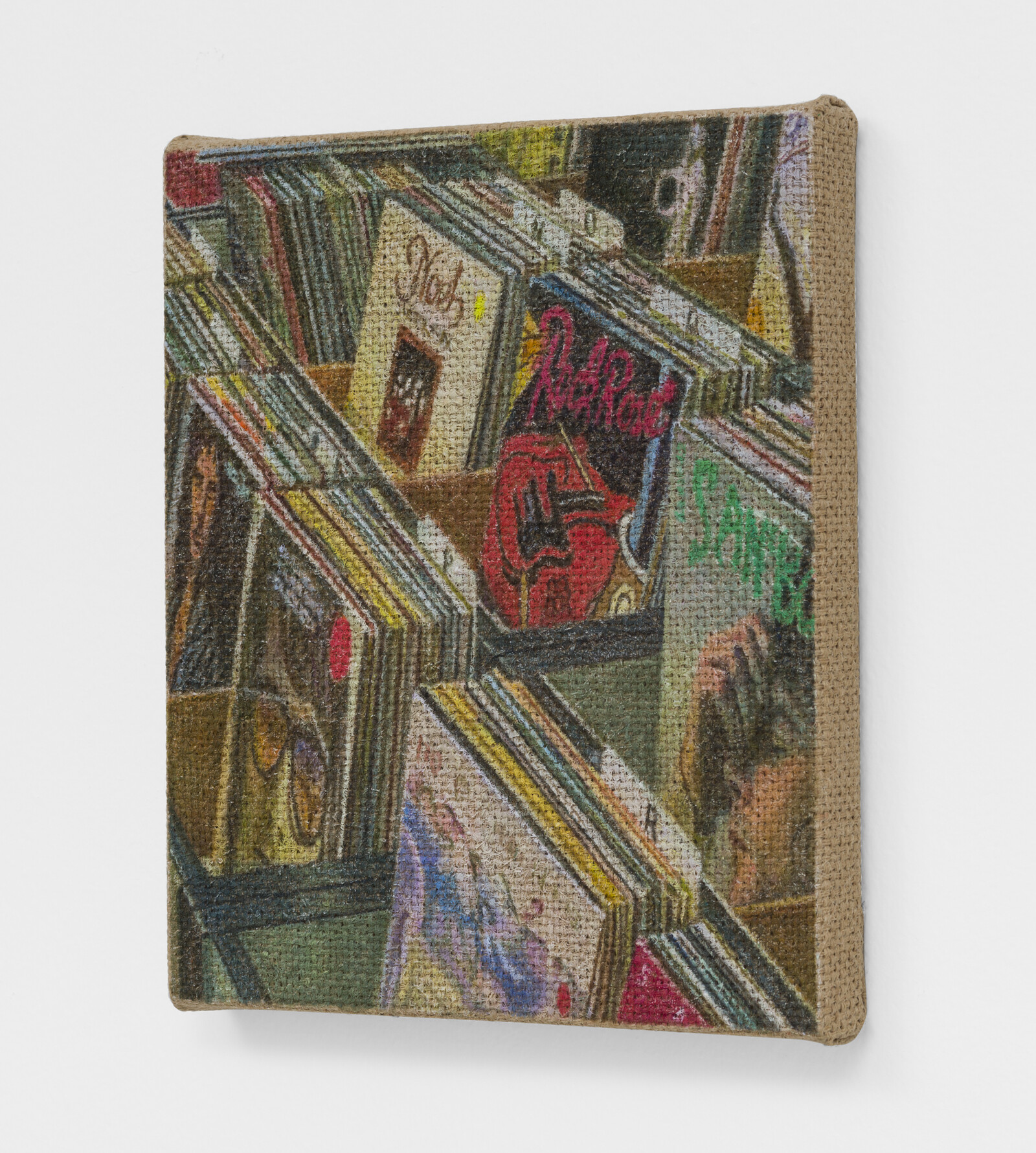

The pictures are further compressed by their cropping. Couch depicts a sofa, patterned in garden-, bruise-, and fire-hued florals of a boomer vintage: the painting’s rough surface, pigmented and oiled, resembles the coarse upholstery of its subject. It lets slip only the tiniest patch of context—a glimpse of a room—in the upper-right corner. The composition is otherwise foreshortened, the pillowy seams of the cushions and pleats cutting a smart diagonal. In Cathedral, Lee’s rendering of tracery and arcades narrows to a blotchy impressionism, as if through a lens with a shallow depth of field. The canted planes in Wallpaper, Elevator, Records, and Security Mirror similarly place their subjects in the middle-distance.

Each image pushes to the edges of the plane but no further: the jute draws raw around the stretcher. The viewer takes in the view quickly, as it were, before being sent back to the paintings’ surfaces and their soft, geometric effects. In Crocodiles, reptilian bodies lie lengthwise across the composition, organizing its knobby grey-greens into rippling strata. Savoy Cabbage curls into brain-like pockets and bumps, a filigree of vegetable ribs jittering against the jute’s shaggy mesh. More than the particulars of their subjects, Lee’s paintings are about juking around the bottlenecks of information transfer. Her found images begin on the internet and end transcribed into these proto-digital mosaics of paint. Like most contemporary art these days, these pieces are then distributed around the world as JPEGs.

Ironically, the works’ low resolution means they do not reproduce well in emails or online viewing rooms. Their intensity is somatic. But the apparent luddite drift of a suite of small paintings rendered on what are, essentially, burlap sacks in this cursed year of the common era is additionally ironic. It may be too much to point out that programmable looms were the precursors to punch-card computers. But Lee’s paintings’ wide, plunging perspectives wouldn’t be possible without the modern camera, at least. They incorporate the low expectations of realist painting in the digital era by surpassing them. In person, the works’ coarseness heightens the viewer’s sense of the semiotics of painting: figure-ground dynamics, photorealism, flatness, gesture, and stroke. Lee underscores a simple point about the dumb materiality of art: the image isn’t everything, there is always more to see.

The pixelation of the wide jute weave gives way to the sense that, where the image breaks down, the surface keeps going. The paintings are full of holes, and are themselves holes of a different sort—windows, even. Perspective—like cathedrals, like couches—is an invention, a technology by which to move without moving. These tight, triumphant paintings lay out the banal dynamism of living with constraints: a small boundary, a rough surface, a discreet discourse. From the mesh of details in the source photographs to those of the jute substrate, these works comment on the base incompleteness of our parsing of the world.