Where is the bright line between life and the simulation of life? And what then are the criteria for assessing aliveness? These questions are forever reconstituted and assessed anew at life’s fringes—around automata, the dead, artificial intelligence. 2017’s prestige AI television series Westworld is only the most recent thinking-through of such questions—a narrative in which robots make a leap into sentience through the injection of a “mistake” memory gesture into their programming. In 1780 Luigi Galvani ran currents of electricity through dead frogs’ legs, the force animated the limbs so that they twitched and jumped (the term “to galvanize”—to electrify into action—is named after the scientist). The repercussions of this experiment, and the question marks it placed over animation, reanimation, and the godlike ability to give life charged through Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), the seminal horror story which drew on Galvani’s experiments to consider the implications of electricity as the force of vitality.

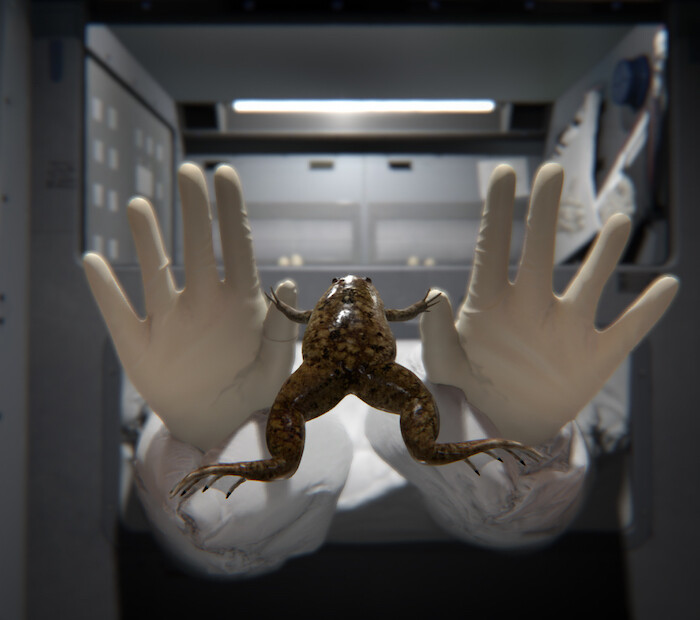

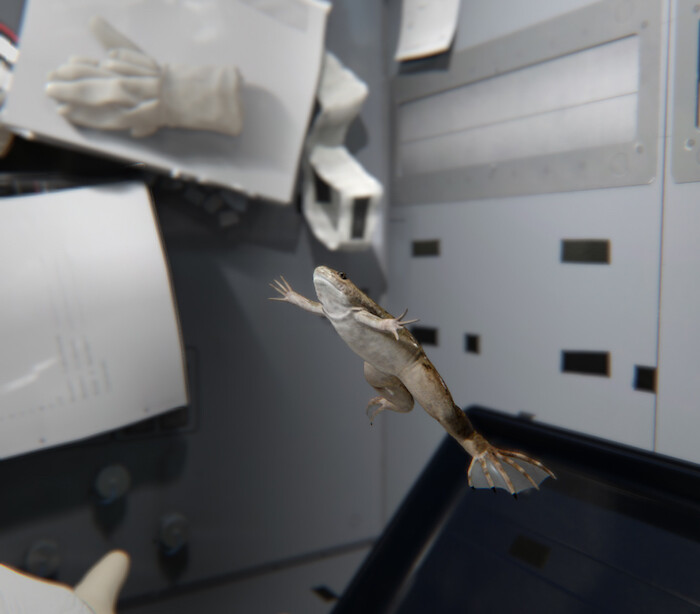

Such histories and philosophical problems are embedded in John Gerrard’s new simulation, X. laevis (Spacelab) (2017), on view at Simon Preston, playing on a large screen in the center of the gallery. Like several of the artist’s previous works, this is a digital animation that renders in real time, much like a video game. A virtual camera wheels around a central scene in which an African Clawed Frog (the Xenopus laevis of the title) appears to be suspended in mid-air. Gerrard has conflated Galvani’s amphibian electrocution with a 1992 experiment carried out on the space shuttle Endeavour to prove that frogs could reproduce in zero gravity. A short YouTube clip of a scientist on that mission losing her hold on a frog in a weightless environment and then gently trying to recapture the airborne creature provides the choreography for the animation, featuring a pair of hands and floating frog, rendered by animators, programmers and modellers. Occasionally the frog spasms in the air, apparently shot through with electricity.

For much of the time, the frog’s front legs are stretched out to the sides while the body dangles below, creating the shape of a crucified figure. Rendered hands reaching for the rendered frog also suggest the Christian iconographic images in which a mortal and God reach to touch, the most obvious being Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam (c.1508–1512) in the Sistine Chapel. Such associations in Gerrard’s work are imbricated with foundational questions of humanity posed by Hannah Arendt in texts such as “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man” (1963), namely: will the journey into technical and mathematical abstraction and a world beyond the senses allow humans to beat death, to leave the earth, to create new machine life? And what are the implications, then, for non-efficient human qualities? Given the choice of medium (live, algorithmic simulation), is there a suggestion that we address the frog as in some sense live or alive?

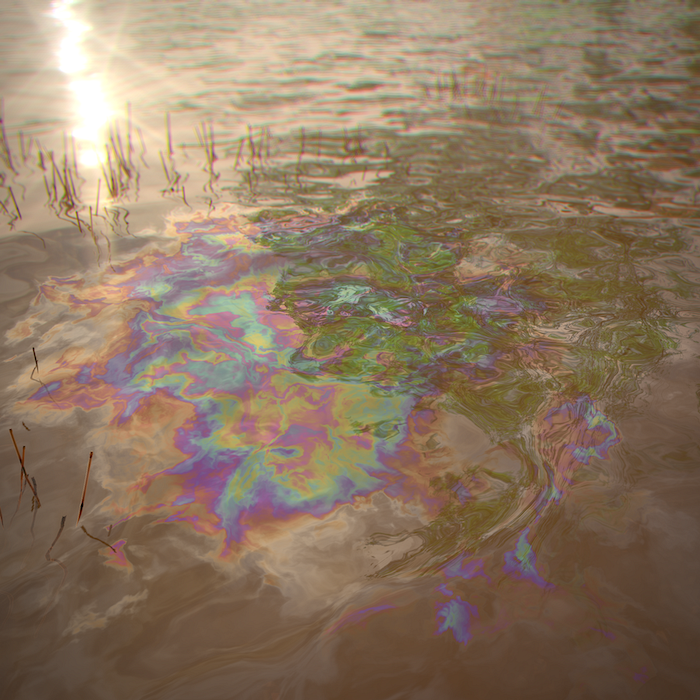

Simulation as form makes sense for the only other work in the exhibition, Flag (Yangtze) (2017) a simulation of a pretty oil spill on the Yangtze, which plays out various algorithmic movement and time patterns connected to the theoretical location of the spill. When I visited in the afternoon in New York, it was night on the Yangtze, so the moon glittered across the simulated spill. In this and Gerrard’s other landscape-based works, such as Western Flag (Spindletop, Texas) (2017), in which a simulated “flag” is created with plumes of black smoke, algorithms play out like a set of toxic weather conditions. The river is poisoned, the sky is filled with smoke – the point being, perhaps, that the technological tools employed to make such simulations are from the outset laden with ethical problems related to power, infrastructure, pollution, and control.

Though X. laevis (Spacelab) raises important questions in beautifully impressive fashion, it strikes me that this work has lost a sense of liveness as, unlike in the Flag works, there is little sense of time or change, only of a suspended scene, and that there is little interference or superfluous activity or movement. It remains, rather, a work of realism. In fact, the most effective moments—in terms of fully invoking issues rather than pointing to them—are those in which the frog appears to eye the viewer, seeming pleading, doomed, accusatory. When we meet this frog’s eyes and imagine its inner life, we’re making an irrational mistake, in fact, because it is a set of codes and commands. In other words, with a lost connection to earthly time and a lack of interference or accident, the work is performing a problem—that our current conceptions of life are tied to these very qualities.