“We all act as if we have no choice but to consume more and more” This quote, from Mongolian artist Ariuntugs Tserenpil, serves as the first of three titles for these reflections on Documenta 14 in Kassel.1 Its label of “the world’s most important exhibition” must still carry some weight. Otherwise, how to explain the lively debate around the calculatedly visionary and/or arrogant decision to split it into two halves—on Greek and German soil—and what might be learned from it? Any attempt to rapidly and exhaustively dissect Documenta 14 is a fool’s errand. Nowadays, any institution of this magnitude is treated as too big to fail and is therefore all the more vulnerable to failure. What used to be a museum of 100 days in a handful of buildings is now a festival lasting 163 days, with 200 authors, over more than 50 venues in two cities far apart. The near impossibility of capturing every facet of the exhibition is built into every viewer’s experience. Such are the diktats of continued growth2 that its organizers must try to oppose from within, while at the same time only pretending to do so. By the logic of subversion, being all the more sincere, and yet, by the logic of opportunism, being forever condemned to insincerity. Documenta 14 pointedly excludes many of the art world’s more recognizable brand names in favor of lesser known “discoveries” (many from nations rarely encountered in international mega events, but still mostly from the Global North) or “rediscoveries” of neglected artists. (Women still account for fewer than half the participants.) Is this a serious, however quixotic, attempt to turn the tables on the market, as with Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore’s Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside, 2017), which, in the Athens show, overlooks the Parthenon? The work, which will eventually be moved to Kassel, consists of a full-scale white marble replica of the “igloo” tent, now associated with people fleeing for their lives. It is a defiant gesture intended to teach Athens something about sculpture and architecture. But isn’t it also an example, however well intended, of the gatekeeper privilege of the curator, like the appearance of so many canvases by Albanian artist Edi Hila in venues across both cities?

An aside that might be important: Does this exhibition take an excessively sociological view of images in general, and of painting in particular? Does it use such work to build storylines so legible that the images themselves fade from view? Are the images selected—including those by highly regarded historical painters like Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) or Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–57)—really allowed to excel at enhancing the overall understanding that the exhibition builds?

“I like it here, there’s a lot of everything, and I need a lot”

I found this quote in a book by Lithuanian artist Algirdas Šeškus, beside 67 black-and-white photographs of the Tibetan shaman Karma Tashi, several of which were also exhibited at the Benaki Museum in Athens.3

The format of this review gives me no choice but to write from the curatorial perspective that has become my own uprooted identity. It also precludes any meaningful politics of mentioning. If I choose to identify a few participants by nationality it is simply to illustrate at least some of the myriad distinct and overlapping concerns that propel Documenta 14. The conflations include: empire / (de)coloniality / indigeneity; body / voice; sound / score; wealth / appropriation / restitution / renunciation.

My first reflections on the opening are best summarized—with reference to the red wool in Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña’s Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) and Quipu Gut (the latter shown in Kassel)—by the metaphor of fiber. In Vicunãs’s work—and perhaps also in the exhibition as a whole—the fiber strikes me as tousled with other fibers into a continuous foldable surface rather than spun into discrete threads ready to be woven together. I’m not suggesting something fluffy or insufficiently thought-out.4 Instead the fiber, crisscrossing other fibers, could stand for all that needs to be brought together—mentally and physically, as in any exhibition—to form any image of the world, any understanding of it.

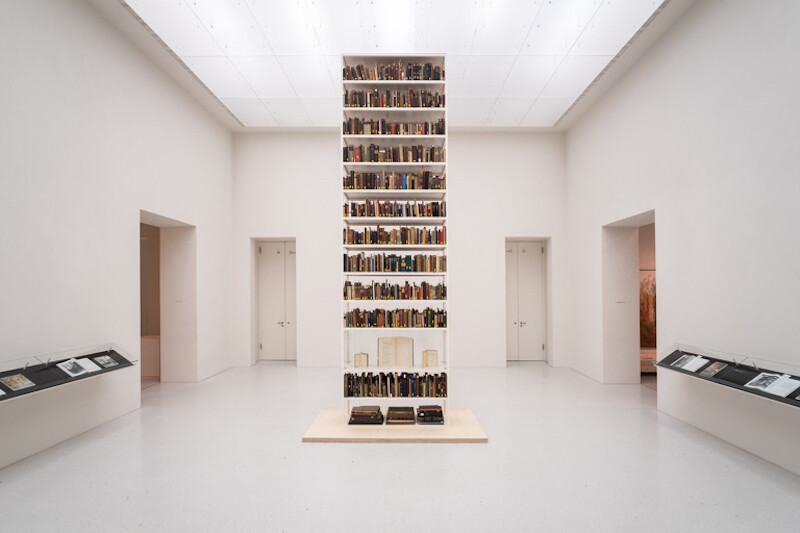

I don’t, therefore, feel the need to dwell on disparities between, say, Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers’s tongue-in-cheek display in magie (1973) of the Wunderblock—a child’s toy comprised of a wax tablet and a sheet of cellophane—that Sigmund Freud used to theorize the operations of memory and German artist Maria Eichhorn’s towering display of Unlawfully Acquired Books from Jewish Ownership (2017), intended to teach Kassel something about evil and its reparation. Or between such object-based work and Chinese documentary filmmaker Wang Bing’s limitlessly non-intrusive display of the limits of human existence in his new film Mrs. Fang (2017), about an elderly woman in rural China drifting away and dying, surrounded by family. In Kassel I began to understand how the many different authors, including the many curators, of Documenta 14 have worked and work together. This is promising, too, for viewers. But I won’t branch out into new metaphors to consider these relations—polyphony, for instance.

The exhibition deserves to be judged for what it aspires to be: an assembly of things, bodies, and minds, so large and manifold that it becomes an organ for understanding the world. Documenta 14 attempts this through the unsentimental poetry of artists selected for their ability to cut to the core of their concerns rather than for their interest in seducing.

“The past and the future are the milk and honey of contemporary intellectuals”

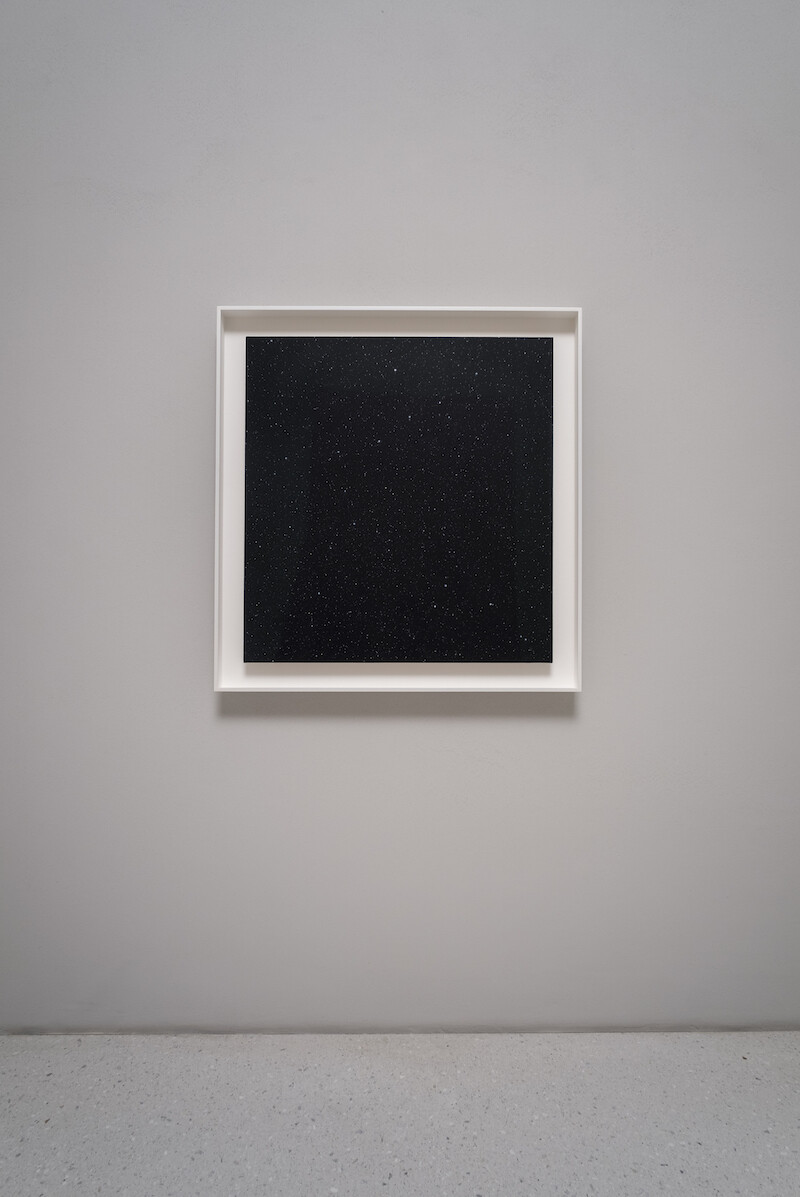

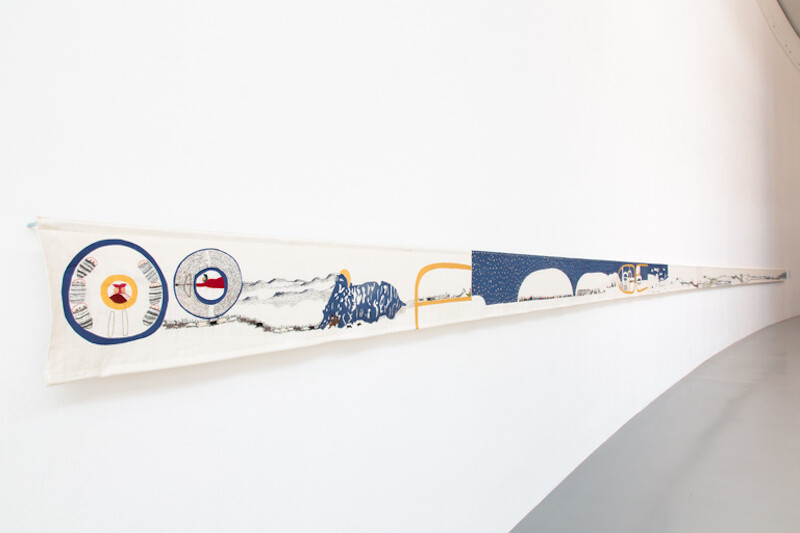

In his multimedia installation Eternal Internet Brotherhood/Sisterhood (2017), Greek artist Angelo Plessas soon moves on from this beautifully light sentence to “transgender occultism” and the “monumentalization of otherness,” but I will use it to wrap up. What is it that Documenta 14 doesn’t do? Is it too much about understanding, as a disciplined practice, and too little about the transformative power of creativity, of the new and hitherto unknown? Is even the unknowable—the future with its upcoming people—being colonized by intellectuals who make exhibitions? In the face of the Exhibitionary Complex, I would always argue in favor of cerebral pleasures: here, to pick a few, the painted celestial vaults of Vija Celmins (Night Sky #23–25, 2014–17) at the Neue Galerie, the short narrative stitches of Britta Marakatt-Labba (Historja [History], 2003–07) at the Documenta Halle, or the long vegetal and social cycles of Agnes Denes (The Living Pyramid, 2015/2017) in the Nordstadtpark. These have in common not only the poetry of precision but also the alchemy of transformation. Indeed, if I were to wish one thing of Documenta 14, it is that the real world shaman of Šeškus’s photographs (who could just as well have been a woman) would step into the real world of the exhibition.

http://www.documenta14.de/en/artists/13520/ariuntugs-tserenpil.

Professor Jim Dator of the University of Hawaii, a portal figure in the world of futures studies, distinguishes four generic “images of futures”: continued growth (always the unmarked mode of capitalism), collapse, discipline, transformation.

Algirdas Šeškus, Šamanas. Fotografo užrašai, Himalajai, 2012 (Vilnius: TVPlay, 2013), 10.

See for instance Thomas Aquinas’s definition of Understanding (in Latin: intellegere, i.e. intus legere or “inward reading”) in his Summa Theologica, as one of the divine gifts to humanity, operating under the impetus of the Holy Spirit and corresponding to the virtue of Faith much in the same way as the sail of a boat corresponds to its oars: www.newadvent.org/summa/3008.htm.