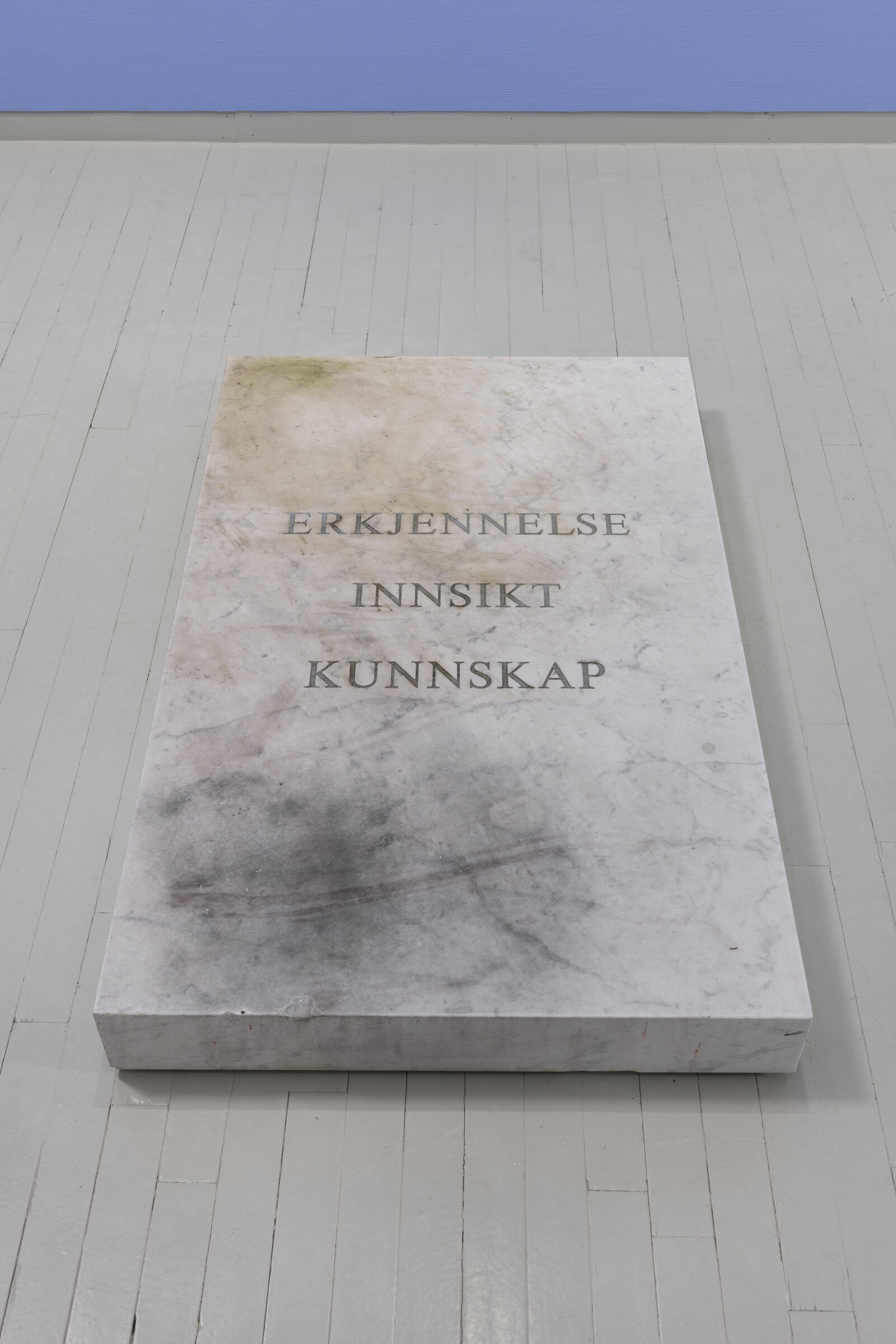

Here lies idealism. This my first impression of a marble tombstone that marks the entrance to the second floor of Bomuldsfabriken Kunsthall. Instead of a name or a set of dates, it bears the words awareness, insight, and knowledge in Norwegian. Hanan Benammar’s sculpture ERKJENNELSE, INNSIKT, KUNNSKAP (2020), re-stages a comment by an established historian on NRK (Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation) regarding a previous work by the artist, Antiphony (2019), in which Benammar set up a calling service that put visitors in touch with strangers to discuss a range of concepts, such as emptiness, chaos, silence, violence, boundaries, and doubt, staging exploratory and open-ended one-on-one discussions. The art historian cited in the more recent sculpture dismissed Antiphony as lacking any significant “awareness, insight, or knowledge.” Those qualities were properly represented by figurative marble sculpture, in this historian’s view, because “marble is art with a capital A.”1

It is tempting to dismiss the notion that art must be made in marble to represent insight as reactionary provincialism, an inconsequential view in the broader context of geo-political crisis. Yet such dismissals echo the ways in which the conspiratorial claims emanating from what Naomi Klein, in her 2023 book Doppelganger, dubbed the “Mirror World” are often treated. Klein argues that to laugh at what appears to be ignorance risks mistaking the function of reactionary commentary. She explains:

For this new political configuration, convincing people of their unproven theories was never the real point—it was only ever a tool. The point, consciously or not, is to foster denial and avoidance. The point is not to have to do hard and uncomfortable things in the face of hard and uncomfortable realities, whether Covid, or climate change, or the fact that our nations were forged in genocide and have never engaged in a remotely serious process of making repair.2

Benammar’s sculpture, with which she chooses to open her first institutional solo show in her adoptive country, is tongue in cheek but it isn’t dismissive. It grapples with the implications of a prominent historian’s offhand denial of the last 400 years of art’s evolving and profoundly dialectical relationship to society. Here lie awareness, insight, and knowledge, the victims of a war on critical culture raging in Norway, but also in Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, a list that grows with each national election; a war that would bury aesthetic situations capable of engendering difficult conversations and return to worshipping the perfect representation of white masculinity embodied in Greek sculpture.

An important context for Benammar’s engagement with this war is Ways of Seeing, a theater play she co-wrote with Pia Maria Roll, Sara Baban, and Marius von der Fehr in 2018, which resulted in a controversy that consumed the artist’s practice for several years.3 Ways of Seeing sought to map the relationship between politicians and key figures from Norway’s business community responsible for funding the far-right media. The play triggered an intense smear campaign directed at the artists, which ended in the conviction of Laila Anita Bertheussen—who was the partner of Tor Mikkel Wara, then sitting Minister of Justice—for “crimes against democracy,” including setting her own car on fire to frame the play’s co-directors for terrorism.

The textile installation Den norske kunstneriske kanon [The Norwegian Artistic Canon] (2024), abstracts the public abuse to which Benammar has been subjected since the controversy erupted. Composed of eight translucent white silk banners hung at odd angles in the center of a gallery, the work resembles a collection of archeological rubbings. Racist comments (the majority of which were made about Benammar) appear to be lifted from stone etchings: “You find bullies in many different contexts,” reads one, “but when it looks like they are a part of an ideology, the latter is usually coming from an area where sand is not in short supply.” The rhetorical reference to Arab societies in North Africa and the Middle East is juxtaposed with a black-and-white silk-screened image of the Shroud of Saint Lazarus of Andalusia from the early eleventh century. The shroud is a gorgeous example of Islamic textile art, but it also includes a reference to Abd-al-Malik al-Muzaffar, who ruled in the first decade of 1000 CE and won several key military battles against Christian cities. The banner effectively illustrates interlocking dog-whistles: contemporary Islamophobic stereotypes and the racist narratives of “inevitable” civilizational conflict rooted in the religious difference used to justify them.4

Throughout “The Soil Is Fertile But For A Distant Seed,” Benammar pays assiduous attention to the images evoked by language and, reciprocally, the way they play into existing language games. This is due in part to the artist’s multilingual background: Benammar was born in Paris into a politically engaged Algerian family, and relocated to Norway in her twenties to find some relief from the oppressive racism directed at the North African diaspora in France. Her engagement with Norwegian aesthetic codes reveals a particular complexity because she refuses to address racism in the abstract, instead persistently interrogating its local manifestations.

The most developed example of Benammar’s grounded investment on view at Bomuldsfabriken Kunsthall is the documentation of a performance from 2021, Dette er vår kropp [This is Our Body], commissioned by the Arctic Moving Image & Film Festival, which happened to coincide with the 300th anniversary of the Norwegian priest Hans Egede’s disembarkation in Kalaallit Nunaat/Greenland. The installation comprises an hour-long video, costumes used during the performance designed by Parnuuna Kristiane Thornwood, and 3D printed sculptures recalling the bread sculptures used as ceremonial objects in the performance. This is Our Body operates in the wake of contemporary debates about taking down sculptures commemorating people implicated in violent forms of colonization and enslavement. Hans Egede is renowned for his missionary work in Kalaallit Nunaat in the eighteenth century, which included the prohibition of Indigenous languages and spiritual practices among other abuses of power.

Staged in large part in Trondenes Church in the Norwegian town of Hárstták/Harstad, Egede’s birthplace, Benammar’s performance assembled an impressive group of collaborators to represent the intersection of the body with religious practice, including the Greenlandish musician Aqqalu Berthelsen. Wearing enormous frilled white linen collars that billow about her, Benammar processes to the front of the chapel to read aloud a letter written by one of her collaborators, Hans-Henrik Egede Nissen, a direct descendant of the missionary, thus embodying a literal embodiment of his legacy. Using bread, she replicated the extremities—hands, feet, face—of a local statue in his honor, in an echo of a Catholic tradition of anatomic ex-votos in which those who suffered from pain in the body would bring baked copies to the church to be healed. Bel Chorus, a local choir, and Cynthia Pitsiulak, an Inuit-Canadian throat-singer, gave a joint performance before the congregation of art-viewers. The performance ended with the entire group of collaborators and visitors ceremonially processing to the seashore to hand the sculptures off to a lone kayak rider, who took them out to sea one at a time to set them afloat, and, ultimately, be devoured by seagulls.

This is Our Body presents a complex rebuttal of the assumption that embodied practice had no place in the Christian faith, or that it was the sole purview of those relegated to the margins of “civilization.” In so doing, Benammer calls attention to the relationship between Nordic ethno-nationalism and Christianity by staging instances of parallelism between Christian ritual and performative practices of those whom ethno-nationalists across the Arctic region would silence. In context of the exhibition as a whole, the work makes a striking proposal regarding the role of art in an increasingly hostile cultural climate. Rather than a retreat into dogmatic self-certainty, the exhibition seems to suggest, it revolves around a deeper and more visceral entanglement with the historical contradictions actively shaping today’s culture wars.

Work descriptions, exhibition handout, Bomuldsfabriken Kunsthall, 2024.

Naomi Klein, Doppelganger : A Trip into the Mirror World (New York: FSG, 2023).

Vassilka Shishkova, “Norway: “Ways of Seeing” and how come that truth is not enough to counter fake news,” IETM online (November 26, 2020): https://www.ietm.org/en/resources/articles/norway-ways-of-seeing-and-how-come-that-truth-is-not-enough-to-counter-fake-news.

A paradigmatic example: Samuel P. Huntington, “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs, vol. 72, no. 3, (Summer 1993): 22–49.