December 12, 2018–March 24, 2019

Arthur Jafa’s newest video The White Album (2018) is an open-ended work. At its premiere at the University of California’s Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive, where the work is being screened on a continuous loop, Jafa went so far as to imply that a newer cut might be ready later that evening. Rarely are moving images premiered in chrysalis states. But a work positioned in rebuke of a terminal condition is one that fundamentally resists stasis and, moreover, tidy conclusions. The method feels appropriate: despite the title, this video is less about whiteness than the porosity, corruptibility, and ultimate fragility of race.

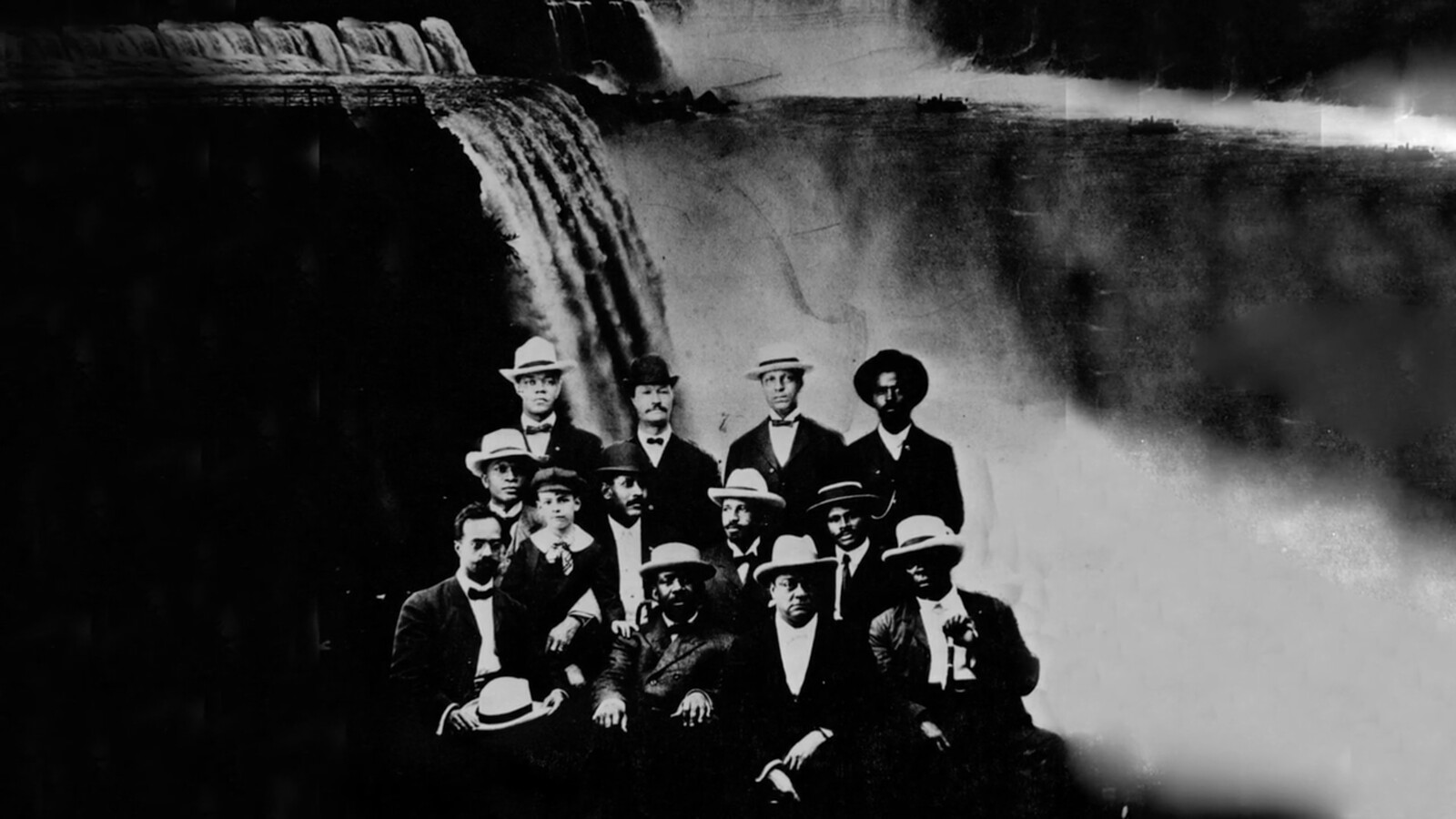

In The White Album, consecutive scenes wobble in and out of focus as Jafa moves between readymade internet footage and his own. Though the imperious watermark of Getty Images never flits into the frame, as it does repeatedly in Jafa’s earlier video, Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), the blear of an image hovering at the edge of legibility remains the prevailing digital facture. His own footage—primarily portraits of staff at his gallery Gavin Brown’s enterprise, located in the historically black neighborhood of Harlem, including Brown himself—is filmed in high-definition. Whether these portraits of the people who work for Jafa (and for whom he works) are intended to expose, or lovingly fetishize, is ambiguous, but I suspect they’re meant to be tender.

Still, this is a work whose other players include the white supremacist Dylann Roof, who in 2015 murdered nine people at a Bible study at a church in Charleston, South Carolina; Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange (1971); Alana Thompson aka Honey Boo Boo; Val Kilmer in the music video for Oneohtrix Point Never’s “Animals” (2016); Erykah Badu; an animated Iggy Pop; O.J. Simpson; and a handful of unknowns, from blood-thirsty US military personnel to blood-chilling gun enthusiasts, German “cybergoths,” and viral video stars. (Cue Jeremy Fry, a white Celtics fan in an ecstatic Bon Jovi lip-synch––an ecstasy paralleled in the rapturous subjects of Jafa’s previous video, akingdoncomethas (2018), 100 minutes of footage of black Christian church services.)

The two longest clips are to-camera confessionals: one from a white teenage girl issuing a vexed diatribe about double standards applied to white people; the other—the longest stretch devoted to any single voice—from a man who calls himself a reformed racist. Modest internet digging reveals this man is not the “Dixon White” of his alias, but a part-white, part-Cuban businessman and aspiring actor named Jorge Moran whose whiteness may be as performed as the syrupy Southern twang he affects. Then again, the footage is also a reminder that whiteness involves a degree of performance, perhaps even of conformity––no whiteness is empirical. Following an opening clip of the multiracial Mahavishnu Orchestra’s John McLaughlin and Billy Cobham warming up––signaling that Jafa himself is warming up, jamming out—is Pop’s craggy voice singing “The Pure and the Damned” (2017). As with any theorizing of whiteness, purity is central. Yet The White Album also investigates what Jafa calls a “psychopathology.” It is, he said, “bound up with the fragility of whiteness as a self-conception […] a conception that exists not as a definition of what it is but as a definition of what it isn’t.”1

As for the open-endedness of the work, Jafa invokes Kanye West: “When Life of Pablo came out, when it was released online, [Kanye] was like, ‘It’s not finished though.’ And it kept changing. […] he continued modifying the mix. […] That, to me, was amazing.” The unorthodox actions of West—whose beguiling “Ultralight Beam” soundtracks Love is the Message—point to an idea that Jafa has cited as a central influence on his thought: Nam Jun Paik’s prediction that “The culture that is going to survive in the future is the culture you can carry around in your head.” Jafa applies this to the survival of black arts in the West: “If you look at where black Americans are strong culturally, it’s in those spaces where our expressions and traditions could actually be carried on our nervous systems […]—those things you can do on a slave ship, on a chain gang, in a prison camp.”2 Unlike the succinct Love is the Message or the propulsive, visually dense Apex (2013), the contents of The White Album feel like the stuff Jafa might be carrying around in his head.

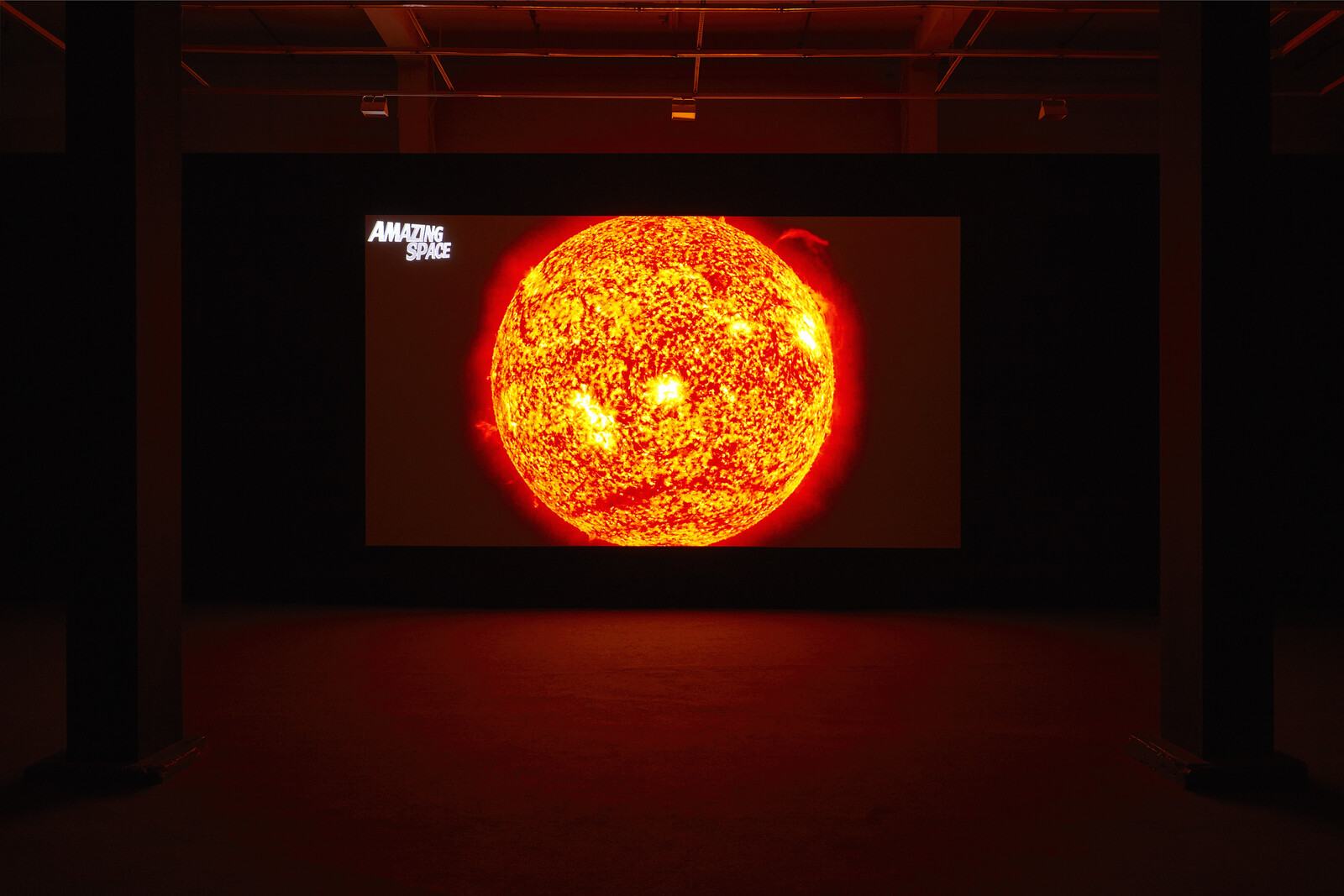

The effects of digital culture on music—a dematerialized consumerism in which Soundcloud, YouTube, and Spotify are more hegemonic than the album or the single—have offered artists the opportunity to continuously re-work material in response to the liveness of digital hosting platforms. (See BLKNWS, an ever-evolving video work begun in 2018 by Kahlil Joseph, Jafa’s friend and collaborator). This hybrid output is symptomatic of the treatment of online culture as an extension of the human cerebrum. The “mind-online continuum” might be one way of describing Jafa’s method, insomuch as it points to a twenty-first-century, techno-capitalist iteration of Paik’s thinking: the culture that is going to survive lives on the internet, itself now increasingly entangled with our human nervous systems.

The video’s irresolution—both unresolved and containing pixelated footage—is impossible not to read as an absence of spiritual or intellectual resolution on the subject. And why should it feel resolved? This is only Jafa’s preliminary attempt at working within the “ideas of black aesthetics […] but don’t necessarily take the black figure as the subject.” It leads viewers to almost-neat conclusions (white people are: violent/silly/bilious/racist/talentless/naïve/etc.), then jars from them, a strategy consistent with Jafa’s stated desire—in the wake of Love is the Message’s zeitgeisty success—to not make anything epiphanic.

Finally, there’s the title. It is borrowed, unambiguously, from arguably The Beatles’s most iconic album, issued at the height of their fame and known for its minimalistic cover: a blank sheath designed by the British pop artist Richard Hamilton. Following the visual cacophony of Peter Blake’s cover for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), The White Album was a mid-career anticlimax, a slackening of something grown over-taut. Jafa’s video is, too, a kind of anticlimax. At a time when the internet is brimming with damning material, he elides indictment. Instead, he assembles a series of images that puncture, if not completely dismantle, whiteness.

All quotes from Jafa, unless otherwise stated, are from conversation between the artist and curators Apsara Diquinzio and Kate Mackay, BAM/PFA, 2018, https://bamlive.s3.amazonaws.com/The%20exhibition%20brochure%20%28PDF%29%20for%20the%20program/MATRIX_Jafa-brochure_201912.pdf.

Ruth Gebreyesus, “Why the film-maker behind Love Is the Message is turning his lens to whiteness,” The Guardian, December 11, 2018.