This exhibition of diagrammatic works juggles some of the most contested categories in contemporary art—and manages to keep all its curatorial balls in the air. Despite the broad sweep of its title, the show is tightly curated and requires multiple viewings for its full scope to set in. With an emphasis on painting, this meticulous grouping of fifty-plus artists undermines simplistic, outmoded art-historical binaries that oppose figuration and abstraction, conceptualism and expressionism, scientism and humanism. To call it expansive feels like an understatement.

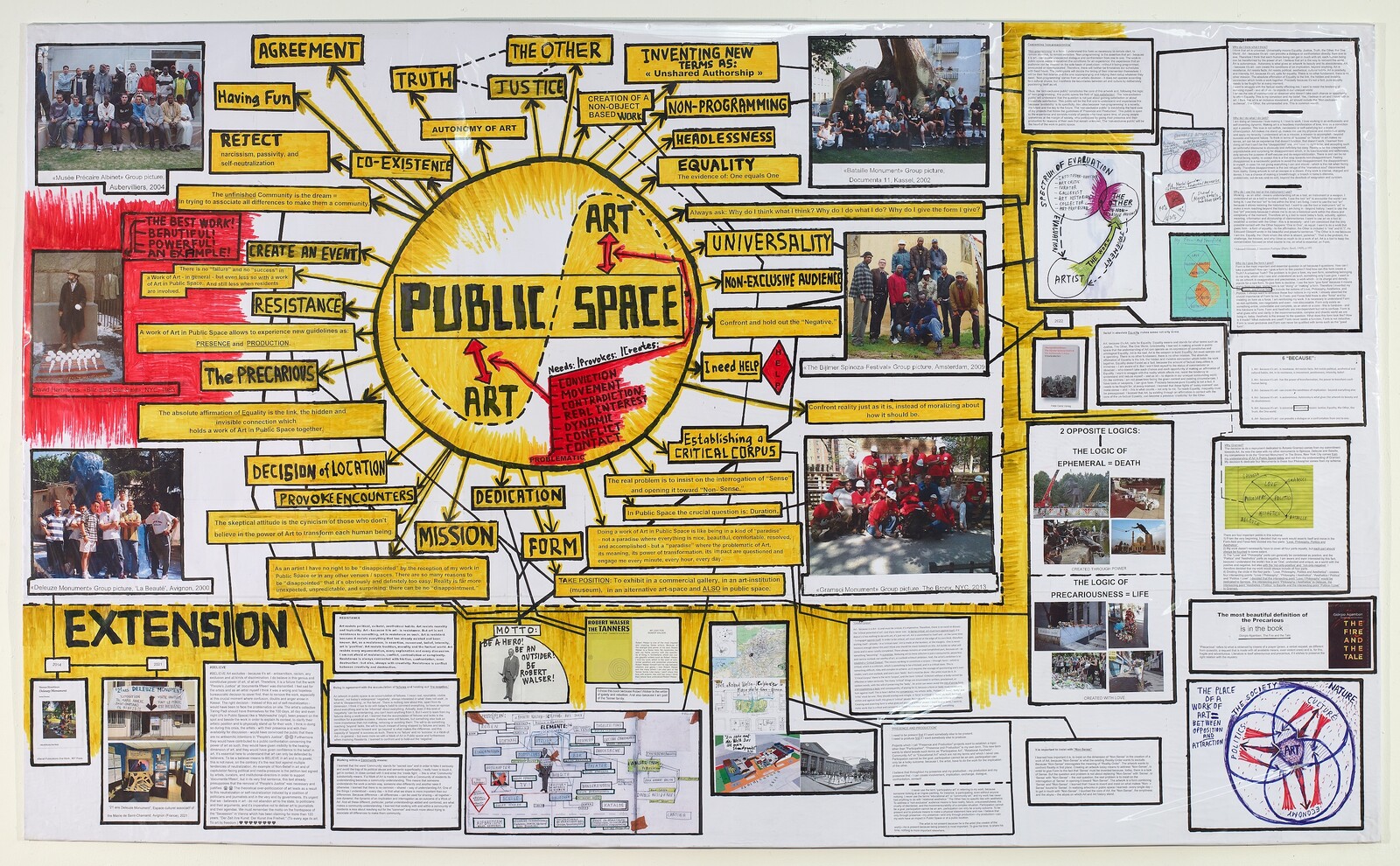

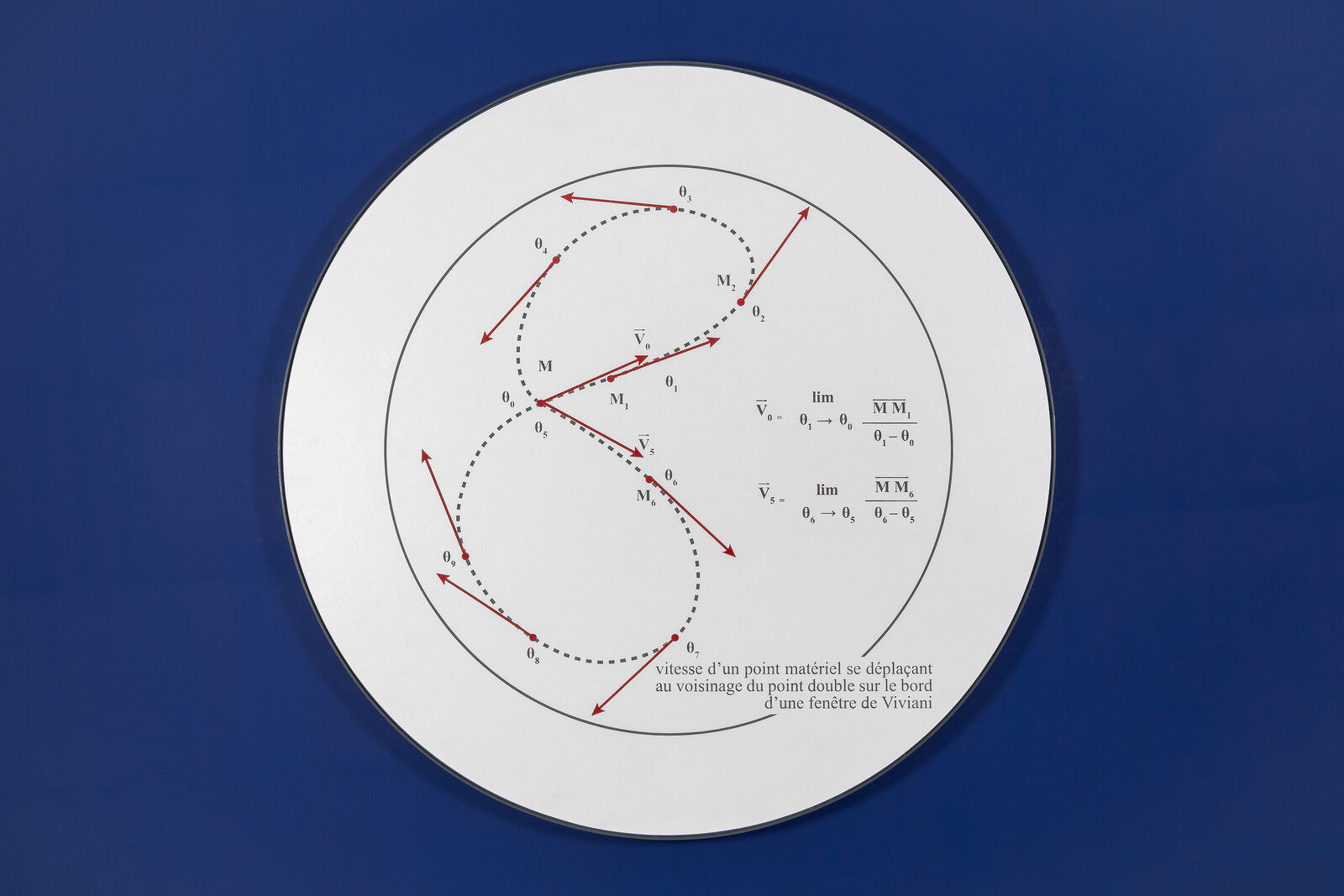

The show takes its title from Thomas Hirschhorn’s Schema: Art and Public Space (2016–22), an exuberant multimedia collage-manifesto. Rudimentary and improvisational, Hirschhorn’s patchwork of ideas and contexts places the works in the show under a utopian-communitarian umbrella—exemplifying David Joselit’s claim in his 2005 essay “Dada’s Diagrams” that “the diagram constitutes an embodied utopianism.”1 Hirschhorn’s Schema might usefully be juxtaposed with Dan Graham’s 1966 work of the same name—sometimes taken to represent the apex of early informatic anti-figural conceptualism. (A show devoted to Graham’s Schema at 3A Gallery closed, coincidentally, several weeks before this exhibition opened.) Graham intended his work to be “completely self-referential” and meant to define “itself in place only as information.”2 Simply a text without pictorial representation, his Schema was, in some respects, the antithesis of Hirschhorn’s. In the terms of Bernar Venet—the artist included in the show whose informatic work perhaps resembles Graham’s most closely—the latter’s Schema is austerely monosemic while Hirschhorn’s is ebulliently polysemic.

The diagram is, by its nature, a medium for institutional critique. Mark Lombardi’s didactic-conspiratorial network diagrams embody that tradition most bluntly, and their guilt-by-association aesthetic has not aged especially well. Diagrams can expose surprising interconnections; they can also oversimplify social relations. Thankfully, this show takes a wider view of the diagrammatic tradition, letting hidden connections subtly reveal themselves. Charles Gaines and Guy de Cointet are nicely paired as text artists. At least five artists in the show share an affinity for the writing of Raymond Roussel. Painting predominates, but the works selected are ecumenical and run the gamut from stark flowchart paintings (Loren Munk, Paul Laffoley) to more abstract paintings that evoke, rather than directly depict, grids (Mike Cloud, Lydia Dona). Younger artists, such as Christine Sun Kim, Tavares Strachan, and Hilma’s Ghost, are well represented.

The show’s concise, well-written catalogue places the works in context without trafficking in much maligned, theory-laden International Art English. Raphael Rubinstein’s introduction functions as a self-aware meta-diagram of multifarious linkages among the works and concepts revealed in the exhibition. The nuanced connections established in the show undermine Eurocentric modernism’s narrative of rupture and progress. Joselit’s foundational essay is arguably more utopian than Raphael and Heather Bause Rubinstein’s curation. For Joselit: “The diagrammatic is characterized by a set of tactical evasions that are among Dada’s great contributions to modernism—the composition of works of art from vectors of force whose lines of flight escape objectivity altogether. In other words, diagrams assault commodity fetishes not by eroding their contours, but by demonstrating their semiotic and physical mobility, which, if intensified sufficiently, may cause the fetish to collapse altogether.”

Many, myself included, would like to see the fetish collapse altogether, but capitalism seems more mired than ever in the pseudo-rationalism of a cultural logic that elevates STEM fields and monopoly technocracy at all costs. It may be the case that the mechanomorphic works of Picabia and Duchamp began to parody the (particularly American) fascination with efficiency, but it is hard to say that the purported escape from objectivity has had much effect on the relentless expansion of hypercapitalism into all corners of consciousness.

“Schema: World as Diagram” doesn’t traffic much in Pop Art’s loving critique of mass culture. Nor do the curators attempt to make assertions as bold as Joselit or Lombardi. They are careful not to confuse correlation with causation or implication with confirmation. In that way, “Schema” implicitly refines and reworks the grand claims of the high theory that dominated literary and art historiography from the 1970s to the ’90s. In so doing, it both presents a critique of retinalism—in the sense of naïve beauty worship—and offers a rewarding outlay of retinal candy that is tasty but never saccharine. The result is a highly successful exhibition that occupies an unusual zone at the (public) periphery of the usual (private) market for art.

David Joselit, “Dada’s Diagrams,” in The Dada Seminars, eds. Leah Dickerman and Matthew Witkovsky (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2005), 221–241.

See Dan Graham, “For Publication” in Dan Graham: Works and Collected Writings, ed. Gloria Moure (Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa, 2009).