The posters advertising “Made in L.A. 2020: a version” show a painting of a tear-filled eye. It belongs to President Obama, a detail from Political Tears Obama by Fulton Leroy Washington, aka Mr. Wash. The work dates from 2008, suggesting that while the rises of Trump and the virus have come to shape how we receive everything, including this abbreviated biennial, causes for anguish predate both. In a series of works on view at the Hammer, Washington’s bright-burning surrealism portrays not only the “political tears” of politicians and celebrities from John McCain to Michael Jackson, but also those of his fellow inmates (the artist spent two decades behind bars after being wrongfully convicted on three drug-related charges), drawing the viewer to reflect on the continuing toll of decades of carceral capitalism in the US.

This biennial, announced in January, installed in June, and previewed by the press in November, still has no public opening date. Several live, performance-based projects, notably those by Harmony Holiday and Ligia Lewis, have taken provisional shapes. As conceived by the curators, Lauren Mackler and Myriam Ben Salah, along with the Hammer’s Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, the show runs recto-verso at two museums—the Hammer and the Huntington. Each of the 30 artists (with a couple of fudges) has work on view at both venues, and each exhibition could stand alone (although the Hammer’s hang is more extensive). But the dual format is sharpest where artists riff across the fold.

At the Hammer, Alexandra Noel shows a suite of miniature paintings on panel depicting disasters, visions, and body horror in mostly cool tones, while a parallel, identically sized but warm-hued grouping is presented at the Huntington. Works by Monica Majoli and Buck Ellison hang tastefully in the Hammer on bare aluminum studs; at the Huntington, Ellison’s Untitled (Cufflinks) (2020), a deadpan still life of the accoutrements of WASP aspiration including tennis balls and an application for a New York Times marriage announcement, nests among nineteenth-century variations on the same theme. Majoli’s piebald paintings of models from the vintage porno mag Blueboy scandalize Thomas Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy (c. 1770), one of the Huntington’s prized possessions. Other memorable works continue this critique of the institution in which they appear. A collage by Kandis Williams sutures Henry Huntington, a streetcar and real-estate tycoon whose manor became the museum’s grounds, to Goya’s son-devouring Saturn. Even Aria Dean’s clunky Ironic Ionic Replica (2020), outwardly a Robert Venturi joke, turns to satire when sited at a century-old institution founded in neoclassical grandeur yet self-conscious enough to brave the barbs of contemporary artists.

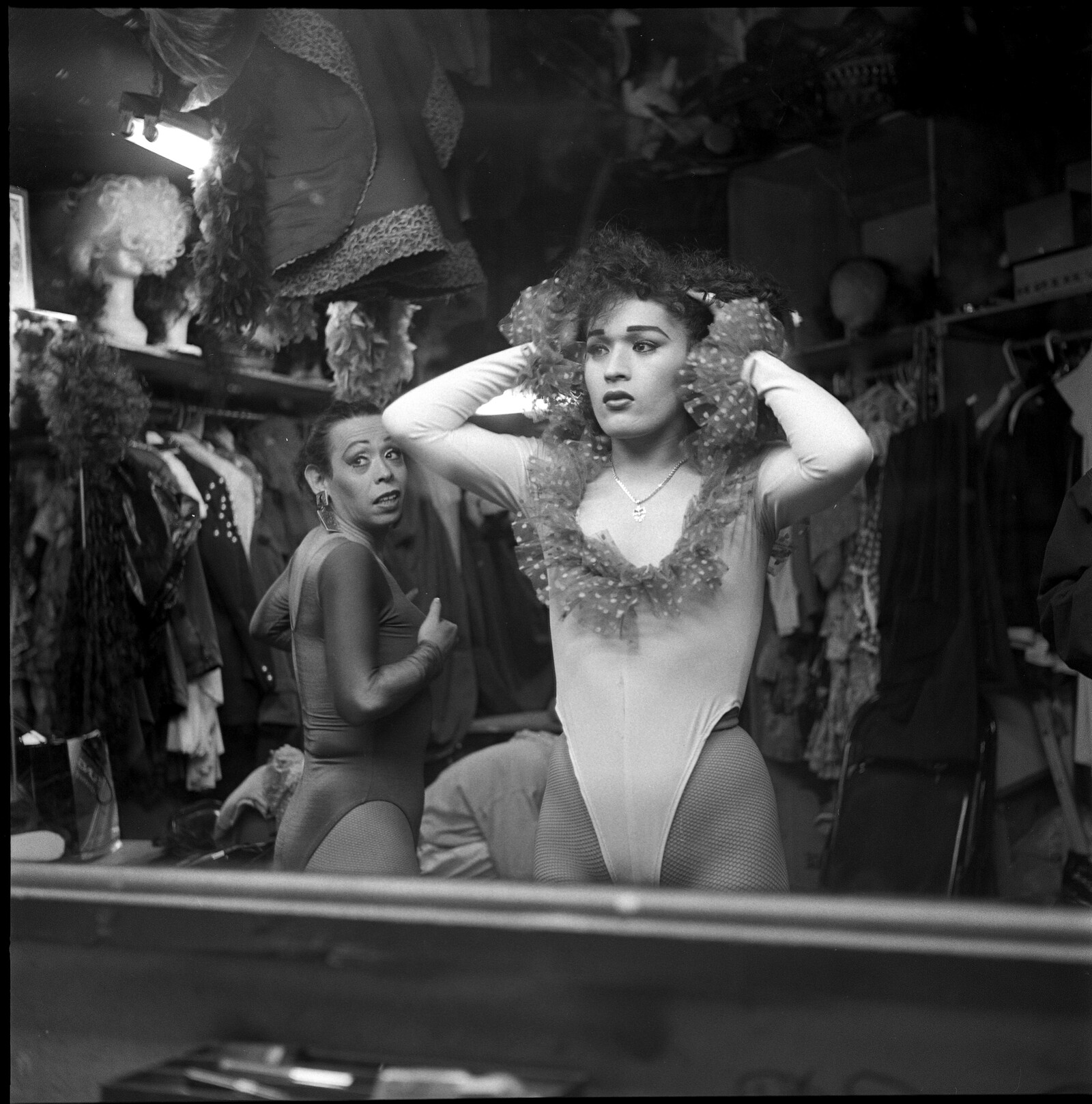

The Huntington is in San Marino, an affluent town abutting Pasadena, beyond the outskirts of Los Angeles proper. With the Hammer in Westwood, the two museums bracket the city west to east. The biennial admits, in its way, that the “real” Los Angeles lies in between—whether through Jill Mulleady’s Someone left the cake out in the rain (2020), a triptych painting showing the hipsters, hawkers, and unhoused of today’s MacArthur Park, or Reynaldo Rivera’s smoky black-and-white documents of the ’80s and ’90s queer club and party scene in Echo Park and Silverlake, long since gentrified away, or Sabrina Tarasoff’s phantastic mini-retrospective-cum-haunted-house conjuring the Beyond Baroque poetry and art gang from 1980s Santa Monica. The art fans out into the streets: text-based works by Larry Johnson are installed on billboards at the corners of MacArthur Park, while the BLKNWS video series, organized by Kahlil Joseph since 2018, screens at a string of Black-owned businesses. The city enters the galleries, too. Sonya Sombreuil, a clothing designer, has sub-curated a display of other artists in front of the Hammer gift shop—in much the same way that the Chinatown pirate radio station KCHUNG, or Mackler’s own Public Fiction curatorial project, were slotted into the biennial in 2014.

Your maps app is unlikely to route you between these ivory towers via L.A.’s teeming surface streets, however, but north onto the 405, 101, and 134 and into the sentient traffic jam of a Hollywood film. Indeed, “a version” presents an L.A. defined by movement, flexibility, and transience, not to mention precarity. Its name aside, this edition is mercifully short on civic boosterism. Instead, the “Made in L.A.” brand represents a sort of institutional constraint, a roof under which to stage the artists’ various relationships to other authoritative frameworks. At the Hammer, a noticeable number of pieces formalize abstract ideas of urbanism—public space and monuments and surveillance—from Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s the input of this machine is the power an output contains (2020), a psychedelic sound pavilion featuring plexiglass chambers lined with wool, felt, carpet, and other textiles, to Patrick Jackson’s Proposal for a Monument (2020), which combines a Maya Lin-style glossy black wedge with a breakfast nook and a water fountain. In similarly drained and dark fashion, Aria Dean contributes production cube (2020), a prison cell-shaped set for a series of monologues, constructed out of two-way mirrors and video feeds of a pacing, discoursing performer, which feels like a Dan Graham-designed waiting room.

The best piece in the troubled 2020 edition of “Made in L.A.” is a project which is emphatically not a work of art. This fact embodies the deep contradictions of the exhibition, and the rich ambivalence with which the artists and curators face them. Ser Serpas’s practice often involves personally collecting and assembling discarded items from the streets surrounding a venue, hoping to reveal something of the neighborhood’s character through what its residents throw away. Yet the artist, who grew up in Boyle Heights before moving to New York, remains in Switzerland due to pandemic travel restrictions: an artist statement insists that “this portion of her practice is dependent upon her unfettered access to the areas immediately surrounding the exhibition site and the exhibition site itself.” Nonetheless, two arrays of garbage have been collected by uncredited museum staff, and a flower bed at the Huntington and a darkened gallery at the Hammer are duly stocked with car parts, marble sinks, children’s furniture, and office equipment. They may still give a sense of the “local,” but explicitly do not constitute Serpas’s own work: rather, the statement continues, “these objects constitute the potential for a work or works, a performance set at an indefinite time.”

The art world ruptured when globalism skidded off the road. And while an emphasis on the artist’s presence feels (perhaps provocatively) old-fashioned, it is refreshingly revealing, unresolved, and contemporary to meet the formal obligations of such an institutional enterprise anyhow, without granting it the name of art. The biennial describes “This City” and “These Times” through a productive misunderstanding of the shaky question of what, exactly, is “made in L.A.”

The public opening of “Made in L.A.” is pending L.A. County guidelines for museums to reopen. Online and offsite projects by Larry Johnson, Kahlil Joseph, and Ligia Lewis are on view now.