An exhibition vitrine in a contemporary exhibition is a knowing nod to long traditions of display. By recreating a form of museum presentation, it relates to what Tony Bennett calls the “museum idea”1 and its way of defining knowledge and, more broadly, power. Museums, according to Bennett, are places where visitors are taught their place in a society. But Vitrine gallery’s two locations, while behind glass, are antitheses of such authoritative presentation. Founder and director Alys Williams’s model is to create shows displayed in large shop window spaces, visible 24 hours a day. Her London gallery, in Bermondsey Square, is relatively simple; the Basel site, in comparison, has an irregular pentagon footprint with walls placed within, its minute office at the center. Though behind glass, exhibitions are effectively on the outside, not a protected interior. The gallery hunkers under a road bridge, surrounded by a fast food kiosk, a spiral staircase, a supermarket, and a tram stop. Artists have to compete visually and aurally with their surroundings and the everyday life that plays out in a space far from most hermetic art contexts.

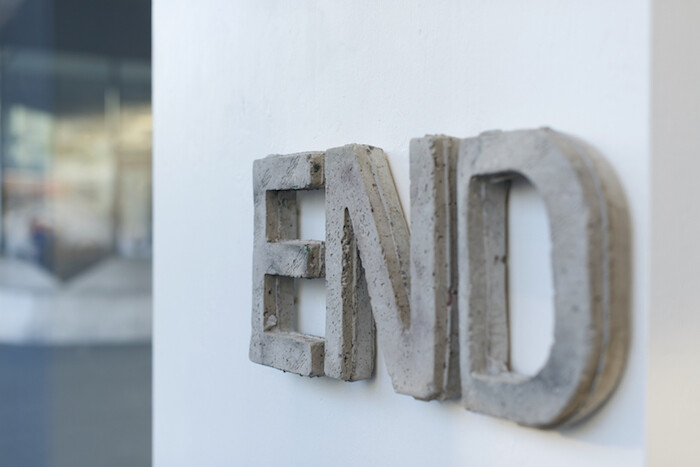

Vitrine Basel thus demands mettle from artists; it is never self-evident that their work should be there, entangled in the mesh of a western city. The site—a good example of the erosion of public space by private interests—is already a microcosm of text, images, and architectures operating on many registers at once, engaging differing degrees of attention, influencing readers more or less directly or obliquely. For the exhibition “Roman-fleuve,” Charlie Godet Thomas makes statements with the economy of corporate identity or signage. Two relief works are single words composed in cast concrete letters, some of which have fallen on the ground and smashed, leaving abbreviated versions behind: OH / MOTHER and FRIEND / END (both 2017). The slightly cartoonish letters are casts of the oasis material into which flowers are stuffed to spell out names in funerary arrangements, adding a mournful and slightly mawkish tinge. The former “OH” reads like a distillate of Philip Larkin’s best-known phrase—“They fuck you up, your mum and dad”2—or a conclusive statement of exasperation. Are they poems, or aphorisms? They function with confident brevity; the space around letters, charged already, resonates still more with what is omitted. Lines Written for and by, No. 3 & 4 (2017) are photographs of black-painted wooden dowels Thomas laced around and through built elements: a wall and a railing. They describe curving arcs, but their crisp, fine lines approach written language; this is form with no meaning ascribed that looks like it is trying to tip into the symbolic. Movable type once took the hand’s written gesture and abstracted it into reusable metal units, then was surpassed by digital printing; Thomas finds play still in the tension between gesture, tool, and mark.

Traditional gallery spaces are compromised in their own ways, but we’ve grown accustomed to those particularities; the competing interests demanding attention in Vitrine’s situation inflect everything on view. A few works made from the curling, spooling cut edges of photographic prints held fast in small canvas-shaped rubber casts feel overshadowed here, even while relating formally to the dowel photographs and continuing the poetic enquiry by borrowing titles from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). As if acknowledging the odd enterprise of bringing together advertising, public information, and art—even pitting art against the others—an unexpected splash of pale tangerine on one wall draws in fresh oxygen, helps works such as OH / MOTHER to breathe. The cultural battle lines are drawn decisively in the work A Sinatra Dinner Show (2017); dimly projected onto a screen in the middle of the gallery in the daytime, more clearly visible at night, a succession of texts selling holiday experiences (“start the party in your hotel lobby… roar along the coast on an ATV…”) are projected, single word by hyperbolic word, a voiceover reading impassively. These flash past quickly, interspersed with film of a beach shore and a close-up of the knobbly texture of a palm tree trunk.

Chopped up, the words have been divested of impact. Around the internal floor nine bright yellow, cast rubber lemons lie scattered: Virtues in Disarray (2013-2017). What is real here, what fake? How do we read intention? Thomas’s response to his site, with its reflective surfaces and its numerous demands on our attention, is to offer texts in multiple forms, toying with different methods of communicating, oscillating between registers. A roman-fleuve is an ongoing, ambitious narrative; this exhibition frames a moment in a continuum, and some bright objects crystallize. Short, sweet words and gestures—OH—that can overcome the mass of impressions of an everyday city. Thus employed, Vitrine Basel does not define the city’s powers but enables countermovement.

Tony Bennett, “Exhibition, Truth, Power: Reconsidering “The Exhibitionary Complex,” in The documenta 14 Reader, ed. Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2017), 341-347.

Phillip Larkin, “This Be The Verse,” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48419/this-be-the-verse.