The people in Henry Taylor’s paintings are usually surrounded by slabs of color, a graphic sensibility he shares with his high school peers and alternative comic book artists Los Bros Hernandez, whom he credits with setting the bar for his work. “I always thought, ‘Damn, they draw so much better than I.’ So I started just practicing my draftsmanship because of them. They intimidated me.”1 Taylor worked for ten years as a technician at Camarillo State Mental Hospital while studying at CalArts, providing assistance to some of the area’s most vulnerable people and at times featuring them in his drawings and paintings, developing the empathetic lens through which he would continue to frame his subjects.

Set in Hauser and Wirth’s Parisian multi-story outpost, and consisting of works made between 2015 and 2023 (the most recent made during a stay in Paris over the summer), “From Sugar to Shit” connects past and present, interior and exterior, public and private. Taylor’s subjects range from famous faces to personal acquaintances, but his frank, inquisitive approach sees both groups as equally worthy of commemoration. It’s not always clear whether he works from memory, archival materials, a live sitting, or a combination of these, but the odd title such as Stand there, don’t move, it’ll be quick (all works mentioned 2023 unless otherwise stated) gives an indication. Collectively these works map out a constellation connecting personal, social, and art histories, and positions itself as a way to think about our value systems.

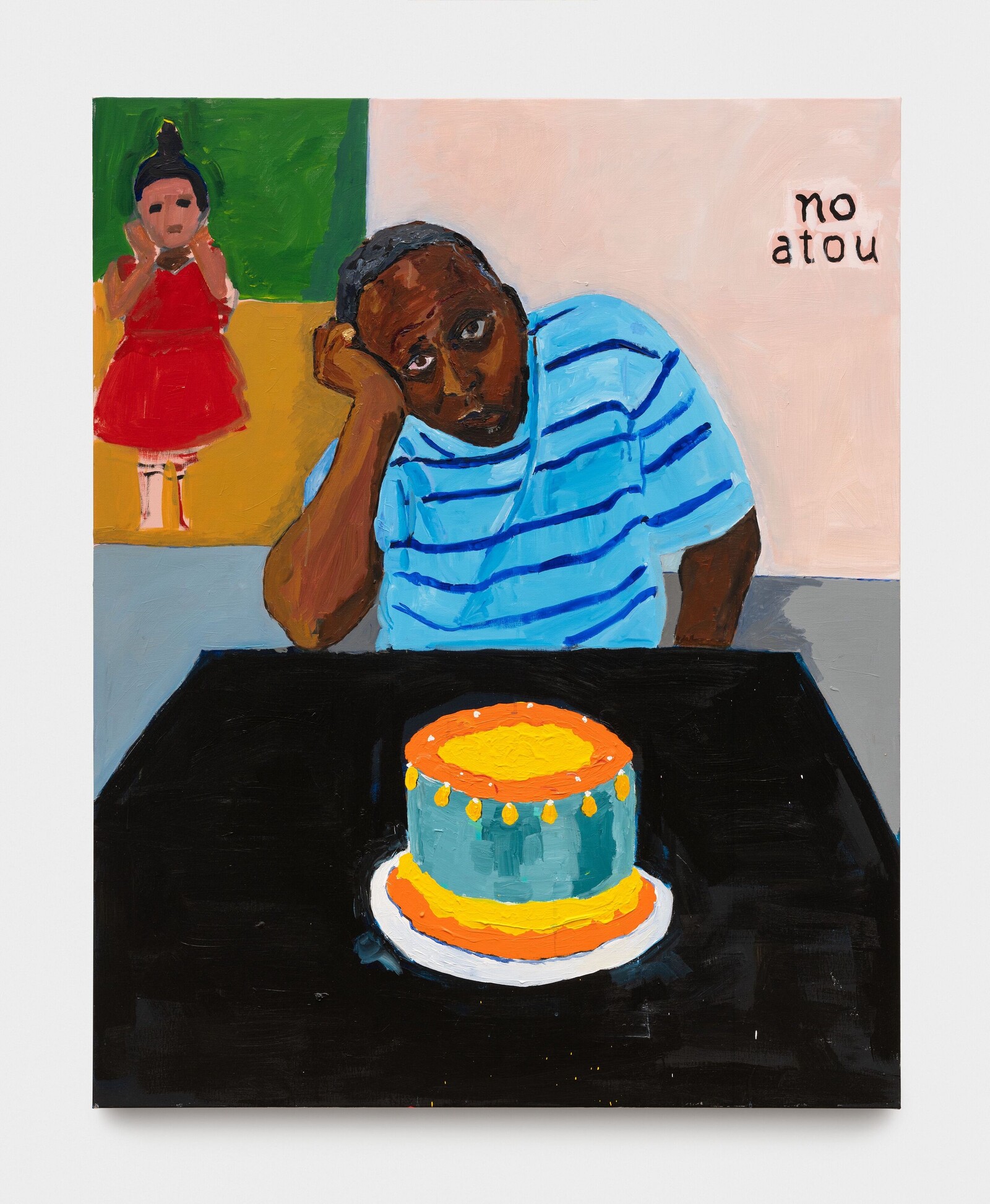

His daughter appears twice: first looking for the cat behind her back in Has anyone seen my cat? and again in no atou, in which the former painting can be seen hanging on the wall behind a self-portrait of Taylor as he sits, visibly glum, at a table celebrating a birthday alone in Paris. Among the recognizable subjects are the late American painter Noah Davis, pictured with the artist in Right hand, wing man, best friend, and all the above! and Michelle Obama, in an eponymous portrait. Taylor, likely reflecting on his own temporary residence as an African American artist in Paris, references Josephine Baker in got, get, gone, but don’t you think you should give it back? The work shows Baker like a sculpture immortalized kneeling in front of a composite backdrop made up of the Louvre and the British Museum, with a ship sailing on the water between them. The impossible image collides timelines and places to depict the forces that have displaced people and objects, giving birth to an amalgamation of cultures and influences that form part of contemporary Black life.

Taylor’s text works punctuate the figurative paintings. On the wall facing the viewer entering the second floor, amidst the busy salon-hang, my eyes flit between ‘Another country,’ Ben Vereen, an untitled pair of gold-laced shoes covered in Black hair, and a text painting in two parts: “And you thought only we ate chitlins,” which reads “Andouillete,” on one canvas and “Chitlins” on the other. The trio are in conversation, the chitlins at the center speaking first to their position as a food reserved for the enslaved people on the plantations, then invoking the Chitlin Circuit, the network of US venues on which African American performers were allowed to perform under segregation, and finally the pork intestine sausage of French culinary tradition.

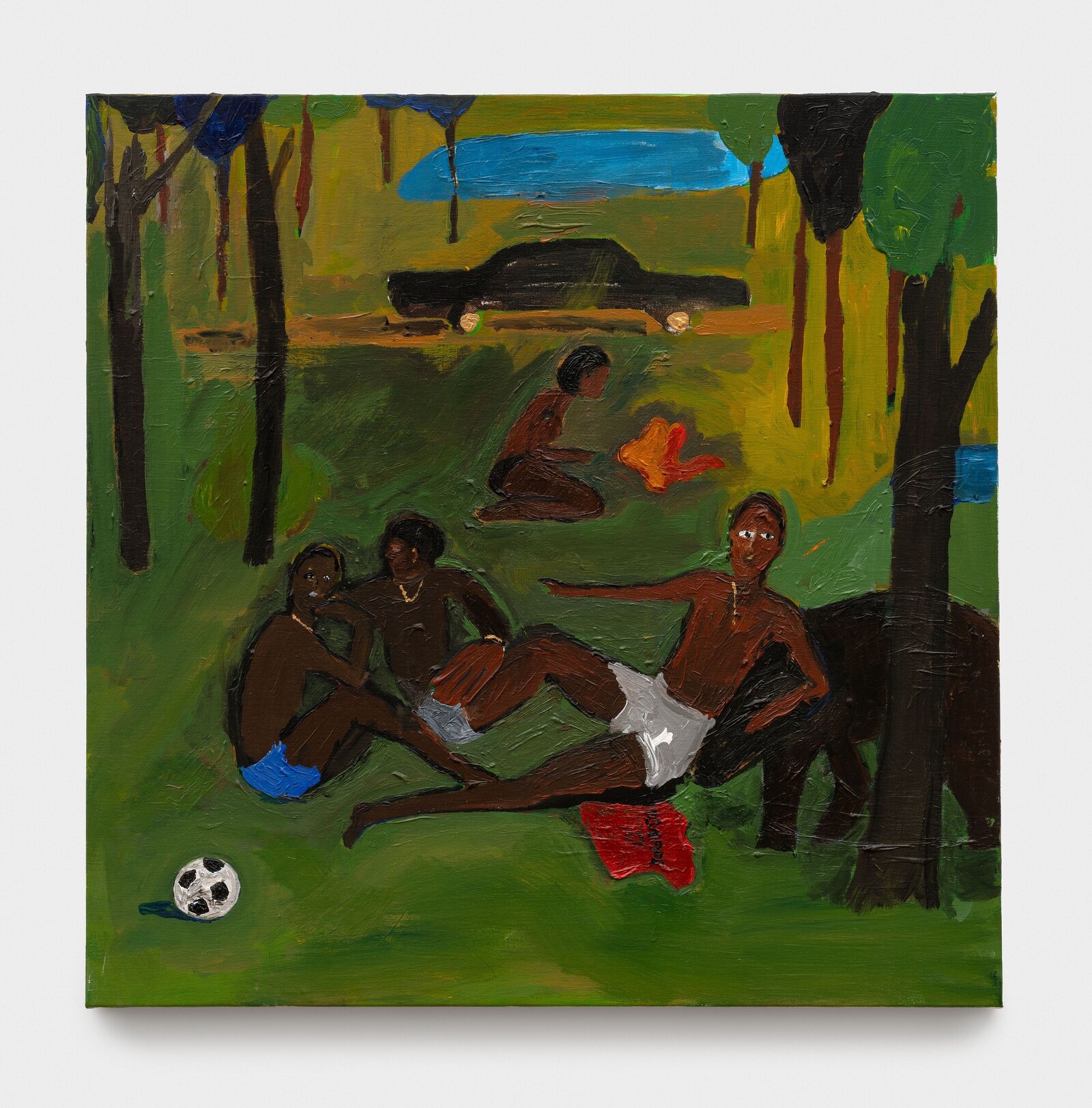

The sculptures, dotted within the spaces, provide visual respite from the many paintings while still fitting neatly within the themes of the show. The one that complements the story best—One tree per family—recalls the David Hammons assemblages, made from the 1970s through to the 2000s, incorporating afro-textured hair. The others are an assortment of mixed-media sculptures formed of miscellaneous objects found on the street or in the trash, sometimes left bare, at times made uniform with a coat of paint. As with the chitlins, there is a transformation that takes place, an inversion of “from sugar to shit”: something that would have been discarded is given use. While Taylor is connecting with elements of African American cultural production, he is also in conversation with canonical Western art history (as in Forest fever ain’t nothing like, “Jungle Fever” which renders a group of young Black people enjoying a day out in a park in a style and composition that references Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862–63). These radically democratic works are unifying and levelling: no person, history, or place is any more or less valuable than another.

Charles Gaines, “An Interview with Henry Taylor” in Henry Taylor (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018), 72.