The question of whether and how contemporary art can contribute to the reform of society is, let’s say, increasingly pressing. Emerging from a cancelled exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, where Karen Archey is curator of contemporary art, this book-length essay posits a “reinvigorated” Institutional Critique as the best available means to this end.1 Featuring artists from Hans Haacke to A.K. Burns, the show aimed to reflect the influence on cultural production of the post-2008 economic recession and social movements including Occupy Wall Street, #MeToo, and Black Lives Matter. In articulating the ideas behind it, After Institutions makes the case for works of art that, by situating their critique in institutions ranging from healthcare to education, might meaningfully change them.

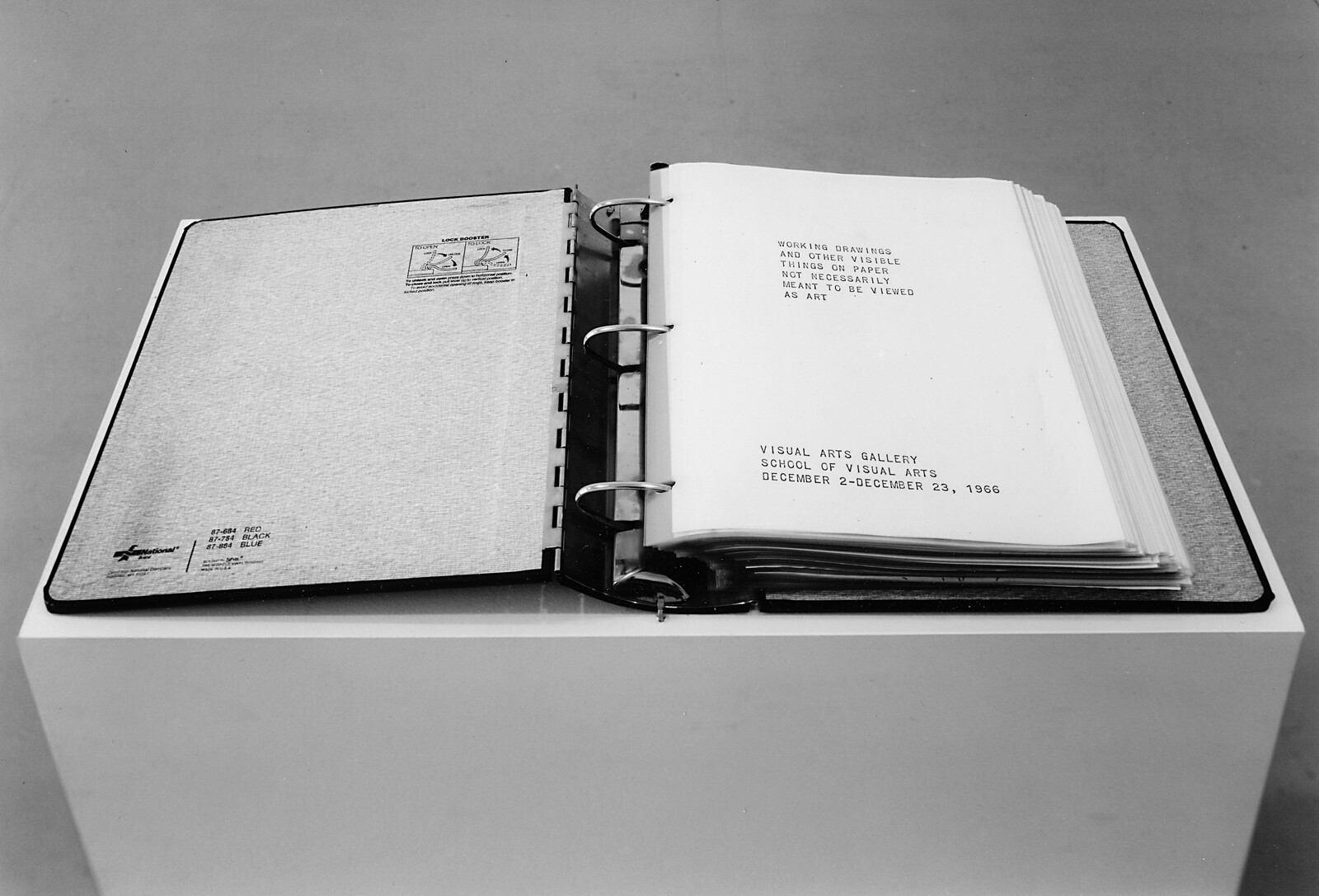

To demonstrate that this is the natural next step in the evolution of what Archey, following Andrea Fraser, calls a “methodology” rather than a movement, she divides a potted history of Institutional Critique into three “waves.” Emerging out of the overwhelmingly white and Eurocentric context of western Conceptual Art in the late 1960s, the first focused its critique on the social and economic structures supporting the art institution. In order to resist its recuperation by the market and foreground idea over affect, the work of pioneers such as Mel Bochner and Seth Siegelaub was stripped of visual content: any tendency towards “aestheticization” was treated with suspicion. The “second wave” took the same techniques and applied them to the Enlightenment institutions that prefigured the art museum. Mark Dion’s investigations into the natural history museum are presented by Archey as archetypal of both the widening of critique’s field and its slow drift away from the studiously objective “anti-aesthetic” of its founders.

These are the tendencies that shape the curve of Archey’s history towards a dramatically expanded field for Institutional Critique, capable of accommodating “representational, narrative, and pictorial” work from non-western contexts alongside work interrogating systems other than the art world. In her telling, the shift to a “third wave” is catalyzed by factors including the influence of organizations such as ACT UP, whose mission went beyond highlighting ethical conflicts in the governance of museums (or, as Gregg Bordowitz put it in 1989, “I have no more questions about gallery walls”).2 Archey identifies Zoe Leonard’s Strange Fruit (1992–97), an installation of stitched-together fruit husks which is both a memorial to the victims of AIDS and an indictment of the US medical system that abandoned them, as a turning point. In communicating not only the facts but the feelings of state-institutional failure, the work demonstrated how critique might be expressive and metaphorical without being reduced to what James Meyer dismissed as mere “political style.”

This opens the door to a new generation of artists—from Cameron Rowland to Christine Sun Kim—whose work more directly addresses institutions of incarceration, health, property ownership, policing, and education. The arena of Institutional Critique now comes to encompasses “the constellation of systems and relations that enable an individual to lead a mentally and physically healthy and fulfilling life.” This is the definition that Archey gives to “care,” and so Institutional Critique is ultimately reimagined for the crisis-ridden present as a “praxis of care”: a methodology for appraising the frameworks of state governance in order to ensure that they meet the requirements of every citizen.

The book’s title is not, therefore, a clarion call for the dismantlement of institutions—no one who advocates this can ever have depended on welfare support—so much as a challenge to the notion that we can ever separate ourselves from them. Even to think of the systems of social organization as existing “outside” our personal experience is to fall into the elitist and ableist presumption that an individual’s access to, for example, education plays no part in determining their future. Citing works by Park McArthur and Joseph Grigely, Archey argues that the first step towards effecting change in our institutions is to draw attention to the often-invisible ways they shape every person’s experience of the world.

Because we cannot separate ourselves—much less art—from these frameworks, that process requires a practice of critical self-reflection for which Institutional Critique supplies the tools. Archey’s book articulates the possibility of a politicized art that goes beyond mere style without sacrificing the possibility of its appeal to a wider constituency. When she concludes that critique is an expression of care for the things “that we love, that we want not just to survive, but to flourish,” she is speaking not only about the future of art institutions, but our increasingly precarious rights and freedoms.

Karen Archey’s After Institutions is published by Floating Opera Press.

After numerous pandemic-enforced postponements, “After Institutions” was, in Archey’s ostensibly neutral yet quietly damning phrase, “not given priority to move forward by the museum’s stakeholders.” The irony of a discursive exhibition about institutional failure being cancelled is not lost on the author.

Bordowitz was speaking in a conversation with Douglas Crimp, quoted in James Meyer’s text accompanying the influential 1993 exhibition “What Happened To The Institutional Critique?” at American Fine Arts, New York. https://bortolamigallery.com/site/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/RG_AmericanFineArt_1993-1.pdf