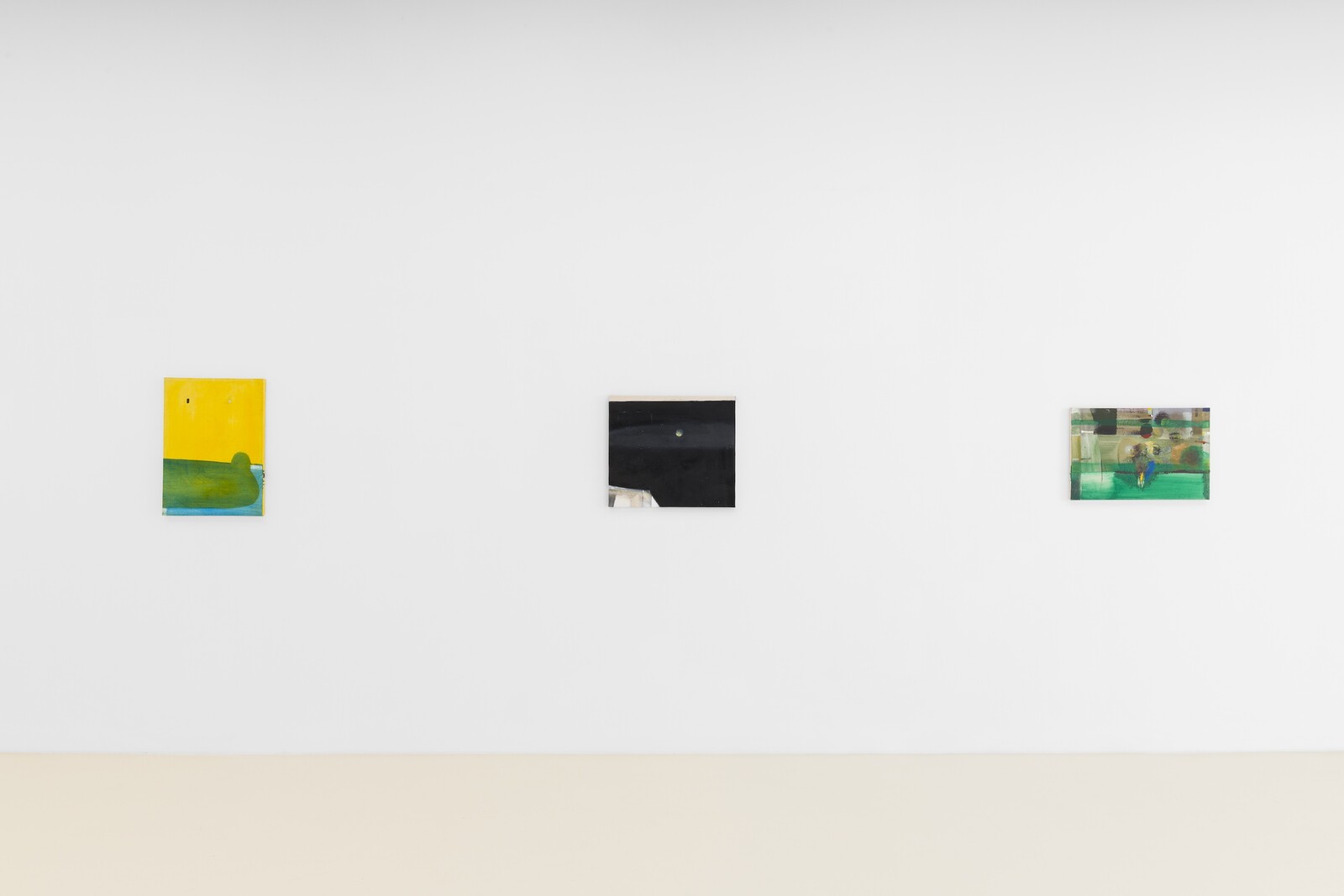

My attention is more or less guaranteed by any exhibition that offers, within the initial sweep of its first gallery, a painting of an airport luggage carousel; a near-monochrome canvas, composed from grubby, rectilinear sections; a close-up picture of a blowjob; and a boisterous abstraction incorporating a tail-wagging dog and a swipe of glitter.

All of the above were painted by the Glasgow-based, Welsh-born artist Merlin James, who has long been notorious for the confounding heterogeneity of his output. At any one moment he might be working on a landscape, an interior, an amorphic abstraction, a painting on translucent fabric showing off its elaborately contrived stretcher or frame, and/or an erotic painting of Betty Tompkins-level explicitness. Sometimes, he has said, he doesn’t know which direction the painting will go in when he starts. Often, his media extend beyond acrylic on canvas to include sawdust, metal filings, clear acrylic medium, ash, floor sweepings, or clipped human hair.

Though widely respected in Europe, he is less well-known in California. “Arrivals”—which shares its wry title with that painting of the airport—is his first exhibition in Los Angeles, and the first time that many local viewers will encounter his elusive and occasionally perplexing work. These modestly scaled, scruffy, and subdued paintings might have felt incongruous here—except that during the first weeks of James’ show, the city was hit by a succession of rainstorms, and days of cool, gray light, with clouds chugging towards gathering showers. The elements rendered them timely.

As with most of his exhibitions, it is gathered from paintings made over several years (2002 is the earliest date in the checklist) thus declining the brittle kudos of newness, contemporaneity, or topicality. James is an artist who often seems somehow out of time, closest in temperament to idiosyncratic, independent historical figures like James McNeill Whistler, Paul Klee, Edvard Munch, or Giorgio Morandi.

One thing that James’s paintings deliver, abundantly and generously, is mood. This northern European tonal baseline—reflective, melancholic, and if not entirely humorless then very dry—is conveyed partly through a sense of place. In “Arrivals,” two paintings—Bridge (2014) and Waterside Buildings (2008)—describe scenes along Glasgow’s gray river Clyde, while another, Between the House and the Studio (2019), shows a terrace, presumably beside James’s riverside home. (The same address from which he also operates the occasional gallery 42 Carlton Place.) These are not places, one assumes, chosen for their picturesque qualities (although that bridge must have been copied a million times by local amateurs), but rather from an impassive acceptance of the way things are, an aversion to sentimentality, and a recognition that more or less any subject can offer an equal shot at making a good painting. Hence: the placelessness of an airport, and the metaphor of a revolving luggage carousel with no luggage on it. Windmill (2002–11), painted on a coarse canvas that resembles burlap and easily the ugliest painting in the show, appears to be an invented scene: not a representation of a place but a representation of a kitschy painting of a windmill, appended with inordinately chunky initials and date.

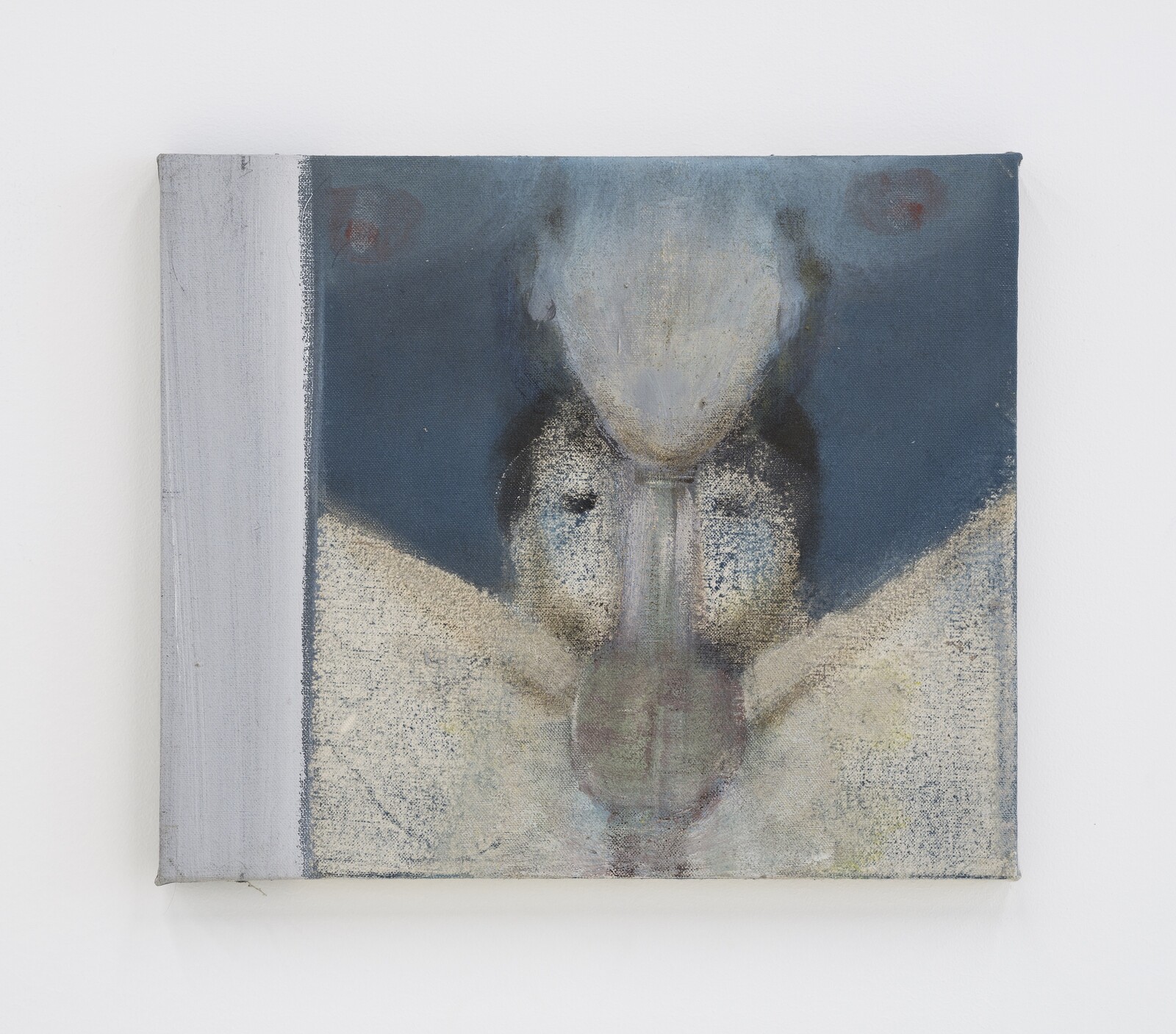

One suspects that James is attempting, at some level, to unfasten his depicted subjects from the real content of his paintings, which has more to do with the fumbling impetus behind the practice of painting itself than with baldly declarative image-making. Many of his canvases, including the velvety black starscape Night (2022), appear to have slipped off their stretchers; in some we see fraying fabric edges glued over other canvases beneath. Very little is held tight in these paintings. The fellatio painting is titled Mirror (2004/22), which may refer to the pale vertical section to the left of the canvas or to the man’s downward gaze through his legs, which fixes our own. Whatever else this painting is about, it is not about fellatio.

It is tempting to align James’s work with the tendency that Raphael Rubinstein, in his 2009 essay, termed “Provisional Painting”: “uncertain, incomplete, casual, self-cancelling or unfinished.”1 Admittedly, James’s paintings do have a tentative relationship to meaning and representation, and in many cases he seems actively to work to undermine them. In Between the House and the Studio, for instance, a sheet of Plexiglas is screwed over just the bottom half of the painting, like an ad hoc solution to guard its thinly-washed canvas from grubby fingerprints, never mind the annoying reflections. Many paintings, including Night, are marred by painterly smudges or scuffs.

But James’s paintings do not strike me as provisional. They are finely tuned, humming machines. Every scuff and smudge is intentional, and contributes to the gestalt of these sometimes vulnerable, sometimes manipulative works. To witness James’s care and deliberateness, look to his paintings’ corners and edges: in many works he tags their corners with colored rectangles which wrap around the sides of the canvas. On Night and its neighbor, Yellow (2016), the paintings’ grounds flow over one edge of the stretcher, but not their opposite sides. More than pictures to be looked at, these are objects to be considered in their entirety. And despite his work’s frequent dourness, it looks a lot like James is having fun.

Raphael Rubinstein, “Provisional Painting,” Art in America (May 1, 2009), https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/provisional-painting-raphael-rubinstein-62792/.