What does it mean to be “international” today? Against a post-pandemic backdrop of hardening borders and resurgent ethnonationalism—in which cross-border solidarity, cooperation, and exchange are increasingly difficult to achieve—the 58th Carnegie International offers a nuanced way forward. The exhibition’s title, “Is it morning for you yet?” is an ancient Mayan saying which also evokes the opening greetings of a video call in which participants introduce themselves across time zones. As the exhibition’s curator Sohrab Mohebbi noted at the press preview, during which he acknowledged that the Guatemalan artist Édgar Calel had introduced him to the phrase, the title also recognizes that we can never exist in different places and be absolutely contemporaneous. By posing a question and inviting us into dialogue, the title suggests how we can be both separate and connected.

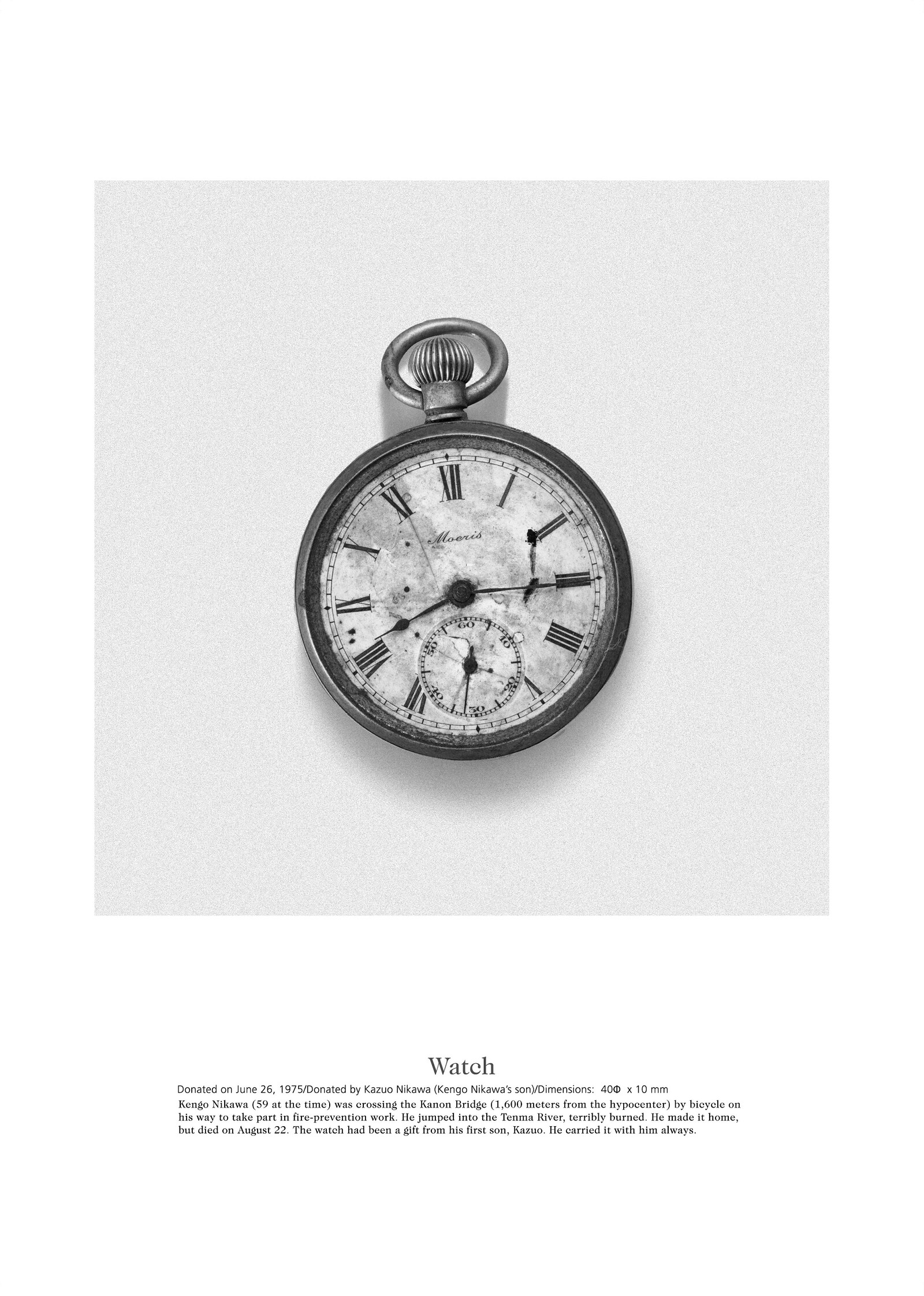

Filling the museum’s Hall of Sculpture are artists whose work is critical of US Empire since 1945. Hiromi Tsuchida’s “Hiroshima Collection” is a set of black-and-white photographs that depict the material traces of the death and suffering that Japanese citizens endured in the wake of the US detonation of Little Boy. Produced over two periods at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, in 1982 and 1995, these objects include a tattered schoolgirl’s dress, melted sake bottles, and a clump of hair presented alongside captions that gradually reveal the brutality of the stories each object carries. Paired with this is right? (2022) by Banu Cennetoğlu, composed of clusters of bright gold helium balloons spread from the ground floor, up past the second story, and towards the skylights above. Each balloon is shaped like a letter taken from the words in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, established by the United Nations in 1948 partly in response to the horrors of the Holocaust. In this version, the phrases are designed to deflate slowly, asking whether or not these claims have the sustainability to manifest the protections that they promise.

The exhibition design, with its violet couches and sheer gray curtains, helps viewers navigate over 500 objects spread over two dozen galleries. In doing so, it stages a theater of the archive. Among the collections represented within the show are the Laal Collection, modern and contemporary art from Iran gathered by artist Fereydoun Ave and selected by Negar Azimi and Mohebbi; “As if there is no sun,” a presentation of the Indonesian painter Kustiyah (1935–2012), organized by the curatorial collective Hyphen— ; “Spores of Solidarity,” curated by Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, including art donated to the people of Chile during the Pinochet regime (1973–90); as well as projects by individual artists including Zahia Rahmani, who gathers publications from the African, Indian, Asian, and Latin American diaspora published between the eighteenth and late twentieth centuries. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s More Than Conquerors: A Monument for Community Health Workers of Baltimore, Maryland (2021–22) is one of the few works directly to address the pandemic. It includes photographic portraits of health workers, paired with text panels of interviews about their struggles working with Covid-19 patients, all framed in an apparatus resembling an IV drip.

“Refractions,” another show within a show, gathers dozens of works—prints, paintings, and videos—that reveal both the geopolitical footprint of the US, with particular focus on Southeast Asia, Central America, and the Middle East, and the solidarities that emerge among artists internationally who have tackled US imperialism. A 1974 poster by the Kuwaiti artist Thuraya Al-Baqsami advocates in Arabic for the freedom of Chilean political prisoners. The late Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Forbidden Colors (1988), four monochromatic canvases—painted white, green, red and black—reproduce the colors of the Palestinian flag, illegal in the Israeli-occupied West Bank when the work was made. Colectivo 3, a Mexican collective active in the 1980s, used mail art as a form of cross-border engagement. Elsewhere are less overt solidarities, based on direct parallels and visual echoes. Susan Meiselas’ 1978 photograph Traditional Indian dance mask from the town of Monimbo, adopted by the rebels during the fight against Somoza to conceal identity depicts a Nicaraguan rebel hiding their face so that they can’t be identified by the authorities. Similarly, Võ An Khánh’s surreal photograph 1972 Extra-curriculum Political Science Class captures North Vietnamese masked revolutionaries protecting their identity from each other. Lugar de Consuelo (2021), a video by Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, is an absurd and surreal staging of a play about the Guatemalan civil war with masked characters who move obliquely through severe architectures in costumes overloaded with appendages. Taken together, the masked figure becomes an enigmatic and ambiguous stand-in for multiple positions, promoting anonymity—and circumventing legibility—in an effort to evade censorship and other forms of violence.

Dia al-Azzawi’s Ruins of Two Cities: Mosul and Aleppo (2020) is a sprawling sculpture that merges the tragic destruction of cities in Iraq and Syria. Both ancient urban centers—one nearly destroyed by an American invasion and occupation, the other razed by the savagery of the Assad regime—put us in the place of Walter Benjamin’s Angelus Novus, watching wide-eyed at the rubble of history. Paired with Melike Kara’s paintings and bleached wallpaper—a disappearing archive of Kurdish culture, including photographic portraits of figures in traditional dress or pages torn from literature—the ruins depicted are not only a city’s fabric, but also the desiccated memories embodied by waterlogged, stained, and torn documents. Sublime decay also marks Dala Nasser’s Tomb of King Hiram (2022), a totem made up of draped canvasses that have been soaked, dyed, or rubbed with materials from the landscape of southern Lebanon, embedded with Spartium and Oleander flowers, rainwater, walnut shells, and blackberries. Similarly, Daniel Lie suggests the fecundity of decomposition and fermentation with an installation that includes cotton fabrics soaked with turmeric, mud, and mold. Oyonïk (2022), by Édgar Calel, includes seventy fired ceramic vessels filled with water, rose petals, and fruit tree branches. It is a delicate work that suggests the possibility of ritual healing, and like Lie’s work a potentially productive approach to decay.

Calel’s piece exemplifies many of the qualities of the 58th Carnegie International: it acknowledges that history is presented to us in ruins, but can also be transformed into something beautiful that nurtures resilience and repair. Perhaps we can imagine Benjamin’s angel not only watching the ruins of history pile up with mute passivity but instead actively working to refashion its fragments into something new. “Is it morning for you yet?” The question reaches out from one subjectivity to another, and in doing so speaks to a desire to begin again.