As clichéd as it seems today, the association of pink and blue with girls and boys is a relatively recent notion. In both style and color, infants’ clothing was largely gender-neutral as recently as the early twentieth century, and it was not until the 1980s that the pink/blue code was fixed to the gender binary. Almost two centuries earlier, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe projected multiple tints and shades onto girls and women: the “female sex in youth,” he writes in Zur Farbenlehre [Theory of Colors] (1810), “is attached to rose-color and sea-green, in age to violet and dark green.”

The alignment of color with gender now seems antiquated. Yet as I walk into “Paintings…,” the latest installation by Paris-born, London-based artist Marc Camille Chaimowicz, I cannot help but notice precisely the feminine palette Goethe described. Rose, sea-green, and violet, with passages of darker green to offset the paler shades, proliferate throughout Cabinet’s exhibition space. The environment offers a subtle, spatial engagement not with feminist discourse, girlhood, or womanhood, but with femininity itself: the material residue of tastes, styles, and their attendant hues that modernity has projected onto people labeled female. Much second-wave feminist literature aims to liberate the female body from such tropes, which are seen as intimately bound up with patriarchal expectations (floral imagery is a prime example). Chaimowicz does the reverse; “Paintings…” liberates femininity from the female body, isolating it as its own productive aesthetic category that can be severed from biological sex, sexual desire, and oppression.

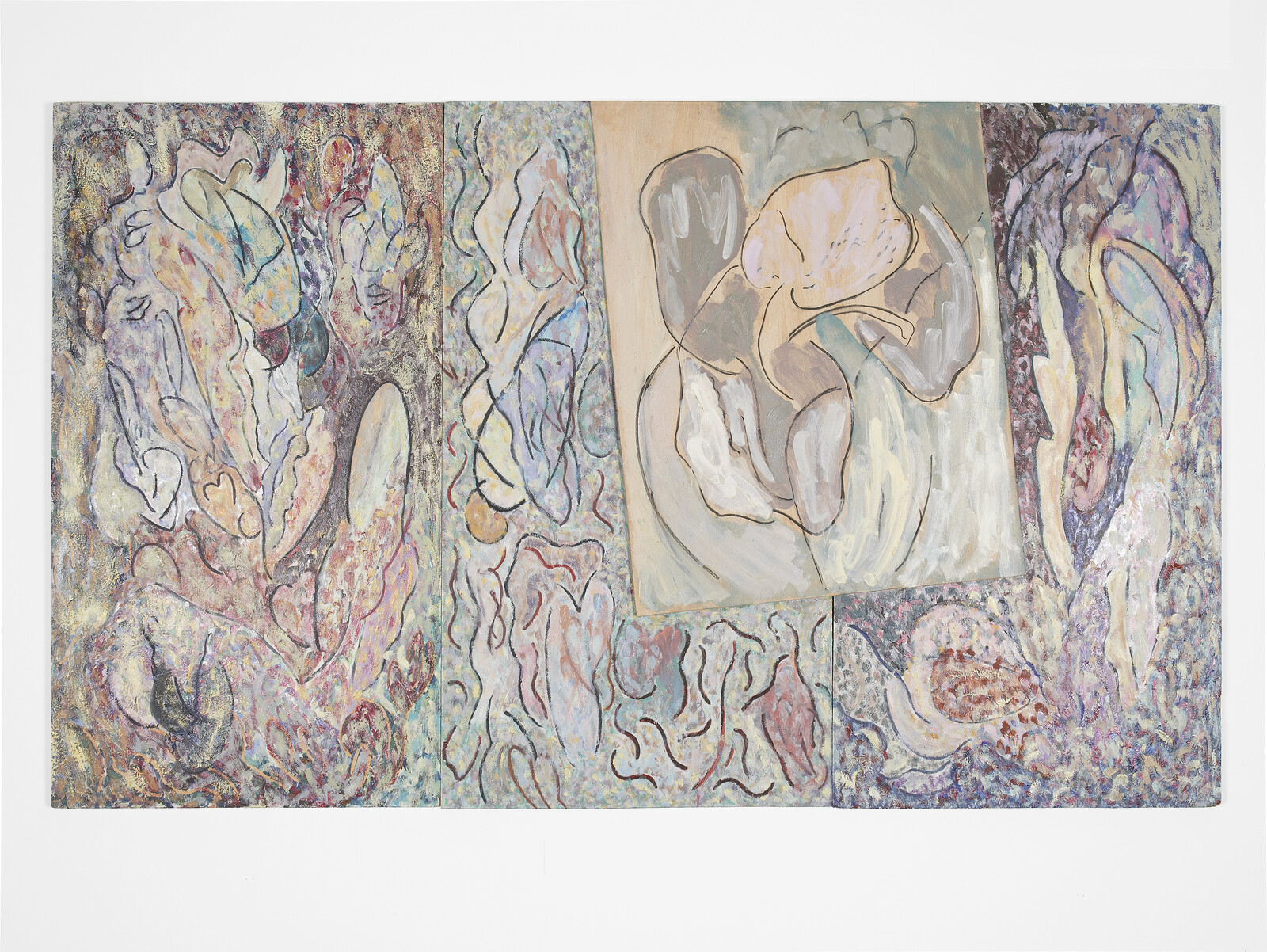

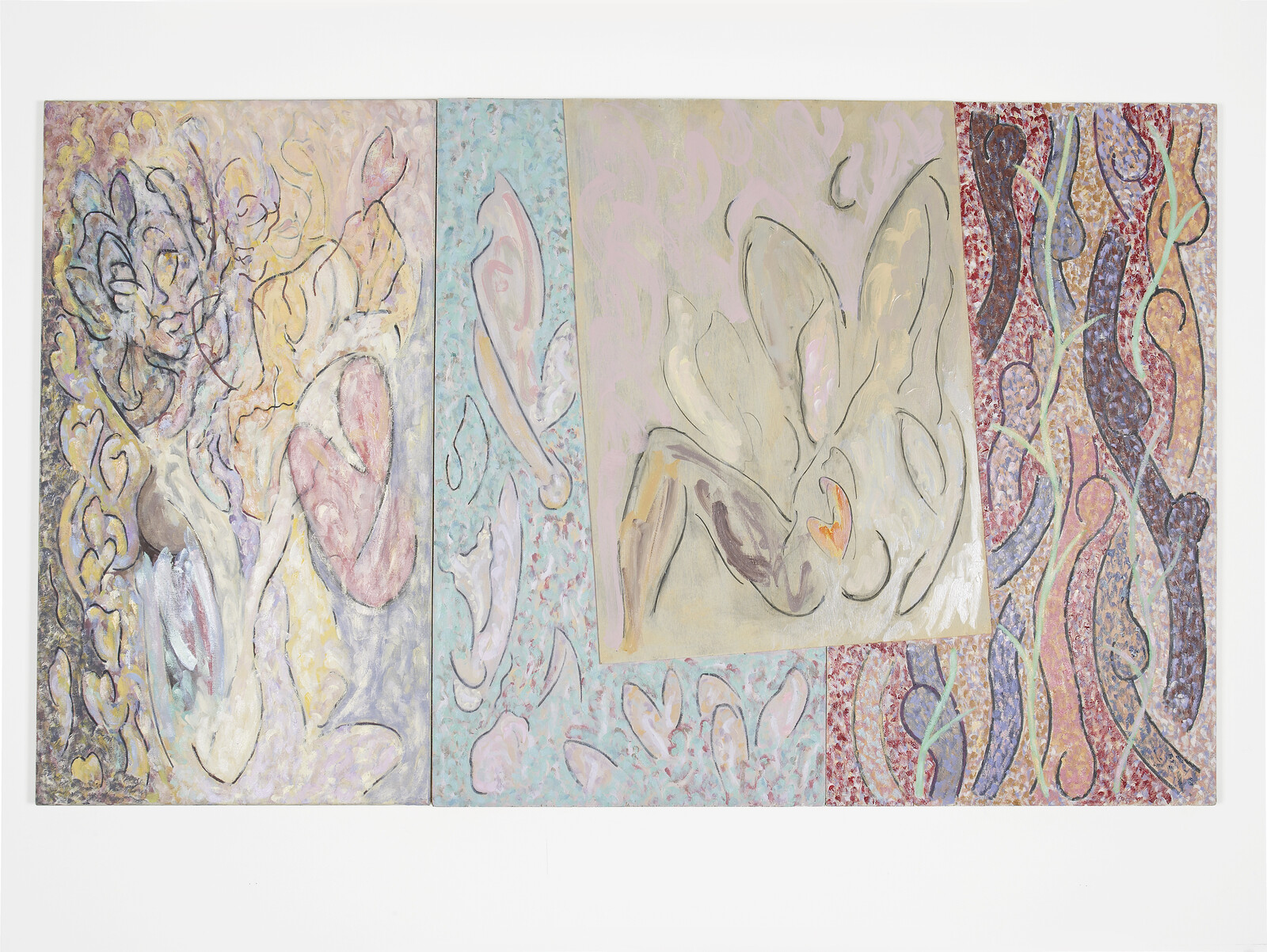

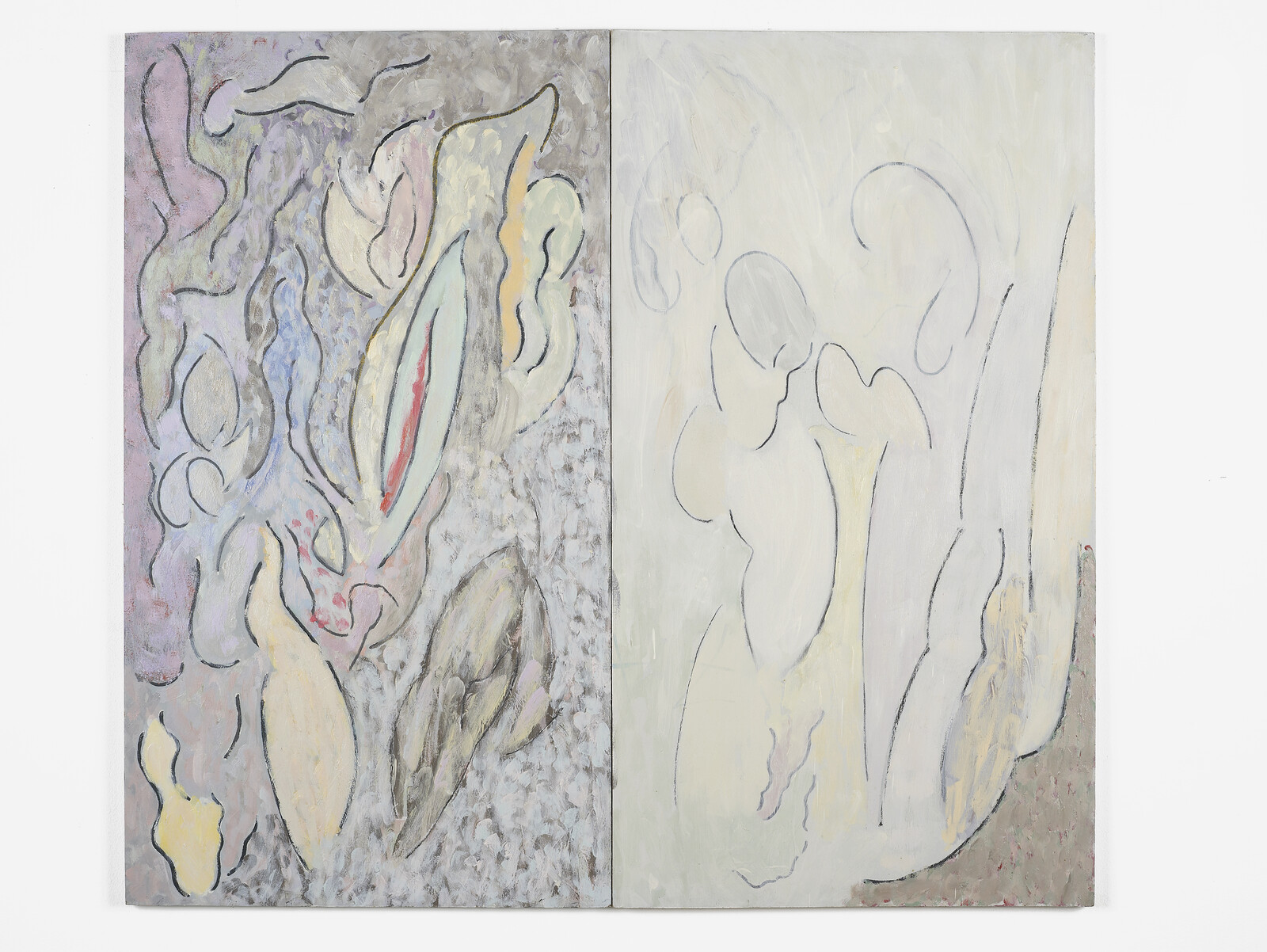

The installation conjures a domestic interior, complete with shelves, curtains, and coat hooks. Opaque wooden screens, some of which are painted violet or rose, break the area into semi-rooms. One screen features a decorative pattern with flowers, ice creams, ribbons tied in bows, and a motif of a bather. Works on board and canvas are placed at intervals throughout the sections. Dating mostly from the late 1980s and early ’90s, these mixtures of oil, charcoal, and (sometimes) collage offer ornamental configurations of corporeal, floral, and vegetal forms, all in outline or broken outline laced over the same selection of colors. A kindred design in rose, violet, sea, and pea green, hemmed by warm hazelnut brown, is spread across a rug.

In a 2010 installation for London’s Bloomberg SPACE, the artist suspended six similarly printed rugs in air, giving the illusion that they were flying. His 2018 show at The Jewish Museum in New York featured a rug elevated on an unevenly raised platform. “Paintings…” returns the rug to its conventional position. This is not to suggest, however, that the installation conjures a functioning domestic interior. Everything in “Paintings…”—including the title—is an illusion, and each form would be impoverished if it were put to use. The alluring translucence of the coat hooks would be obscured by the hanging of coats; the paper vases would not accommodate water; the books are fake, but they possess beautiful covers adorned with drawings of putti; the single wooden chair is an impressive structure but does not look comfortable enough to sit on; a rail of garments is tucked away in a corner, as if to avoid interpretation as wearable clothing. For his landmark installation Celebration? Realife at Gallery House, London, in 1972, Chaimowicz entertained visitors in the gallery, sharing tea and conversing with them, diminishing the barriers between artist, artwork, and audience. “Paintings…” offers none of this hospitality. It invites, but does not accommodate.

Yet there is a vital thread tying “Paintings…” to Chaimowicz’s early work. Following the success of Celebration? Realife and performances such as Table Tableau (1974), in which the artist applied makeup with his back to the audience, critic Hugh Adams proclaimed that Chaimowicz seeks to shift “his (male) ego from the centre of stage. He would like it to become invisible, eliminated by lights so strong that they remove the performer from sight.”1 Over forty years later, a similar wish can be identified in the staged sanctuary that is “Paintings…” Through color and an equally feminized emphasis on ornamental prints and objects, Chaimowicz creates a space in which all traces of the (male) practitioner have been carefully removed. Such colors and forms are characteristic for the artist, yet by their very nature they resist being seen as the signature of an individual. So while the press release informs me that “Paintings…” is based on the artist’s own apartment—situated three floors above this ground-floor gallery space—and a previous installation, I felt only his absence and my presence. It was unsettling to be caught between this sense of my physical self—emphasized by the inclusion of two full-length mirrors—and the illusory, inhospitable aspects of the installation that simultaneously kept me at bay.

Critics who praise Chaimowicz’s art often use words like “sensuous,” “intimate,” “private”: all adjectives associated with the feminine. These qualities are on the edge of what Jean Fisher, in her discussion of Celebration? Realife, terms a “grotesque sentimentality,” a condemnation echoing Hugh Adams’s perception that some may see Chaimowicz’s work as “embarrassing” or “prissy”. 2 Such gendered language calls to mind an archetype identified by Simone de Beauvoir, one of the artist’s key influences. In The Second Sex (1949), the author describes an “adolescent boy [who] becomes embarrassed, blushes, if he meets his mother, sisters, or women in his family when he is out with his friends.” It is not simply their sex that is shameful to the boy, but femininity itself, a fantasy described elsewhere in the book as “all the fauna, all the earthly flora: gazelle, doe, lilies and roses, downy peaches, fragrant raspberries […] precious stones, mother-of-pearl, agate, pearls, silk.”3 This inventory of textures, tastes, and smells could be the starting point for any number of the works in “Paintings…” By reclaiming and liberating femininity, Chaimowicz courts, and thus dissolves, some of the shame that is arises when certain qualities, tastes, styles, images, and colors are ascribed to a particular gender. This is an invitation to the visitor, not to get comfortable, but to reflect.

Hugh Adams, “British Performance Art,” Studio International, July/August 1976.

Jean Fisher and Stuart Morgan, Marc Camille Chaimowicz: Past Imperfect 1972-1982 (Liverpool, Londonderry, and Southampton: Bluecoat Gallery, The Orchard Gallery, and John Hansard Gallery, 1983).

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, eds and trans. Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010) 174.