Days before New York’s galleries shuttered in mid-March, I saw exhibitions of figurative paintings by Jutta Koether and Jana Euler that read to me like biological weapons threatening the patriarchal history of art. Worried that I may have become an invisible conduit for viral contagion, my heightened bodily self-consciousness found echoes, first, in Koether’s exhibition “4 the Team,” the German-born painter and musician’s first solo show at Lévy Gorvy. For this mini-survey of the artist’s works on canvas from the 1980s to the present, Koether variously adopts vulnerability and heroism as painterly moods. Her practice—born out of the discourses of appropriation, feminism, and institutional critique—often hinges on the theatrics of installation: stage lighting, transparent glass walls, and performance. Here, she chose to leave the gallery’s elegant three-story space free of spatial interventions, allowing for an associative reading of the paintings.

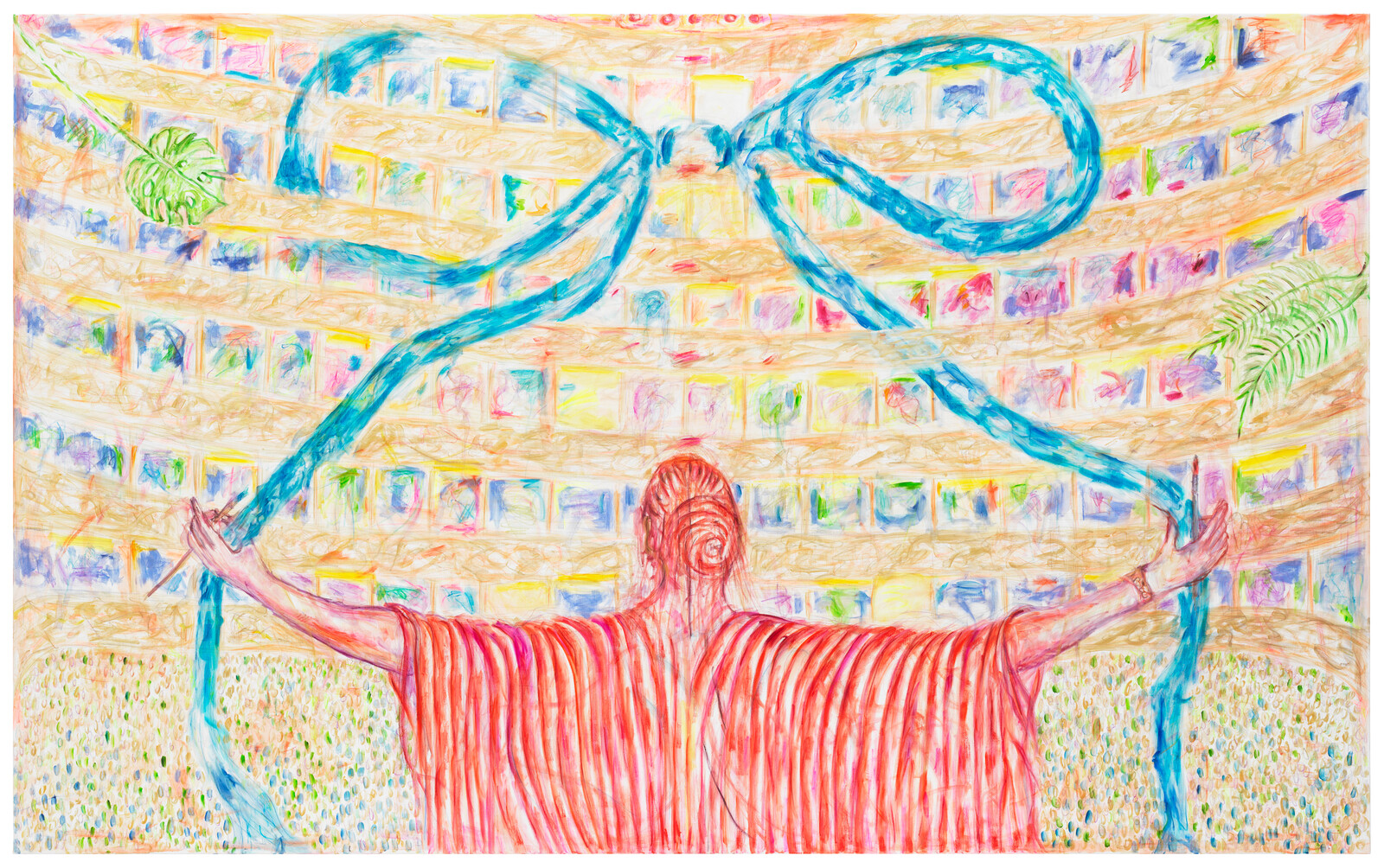

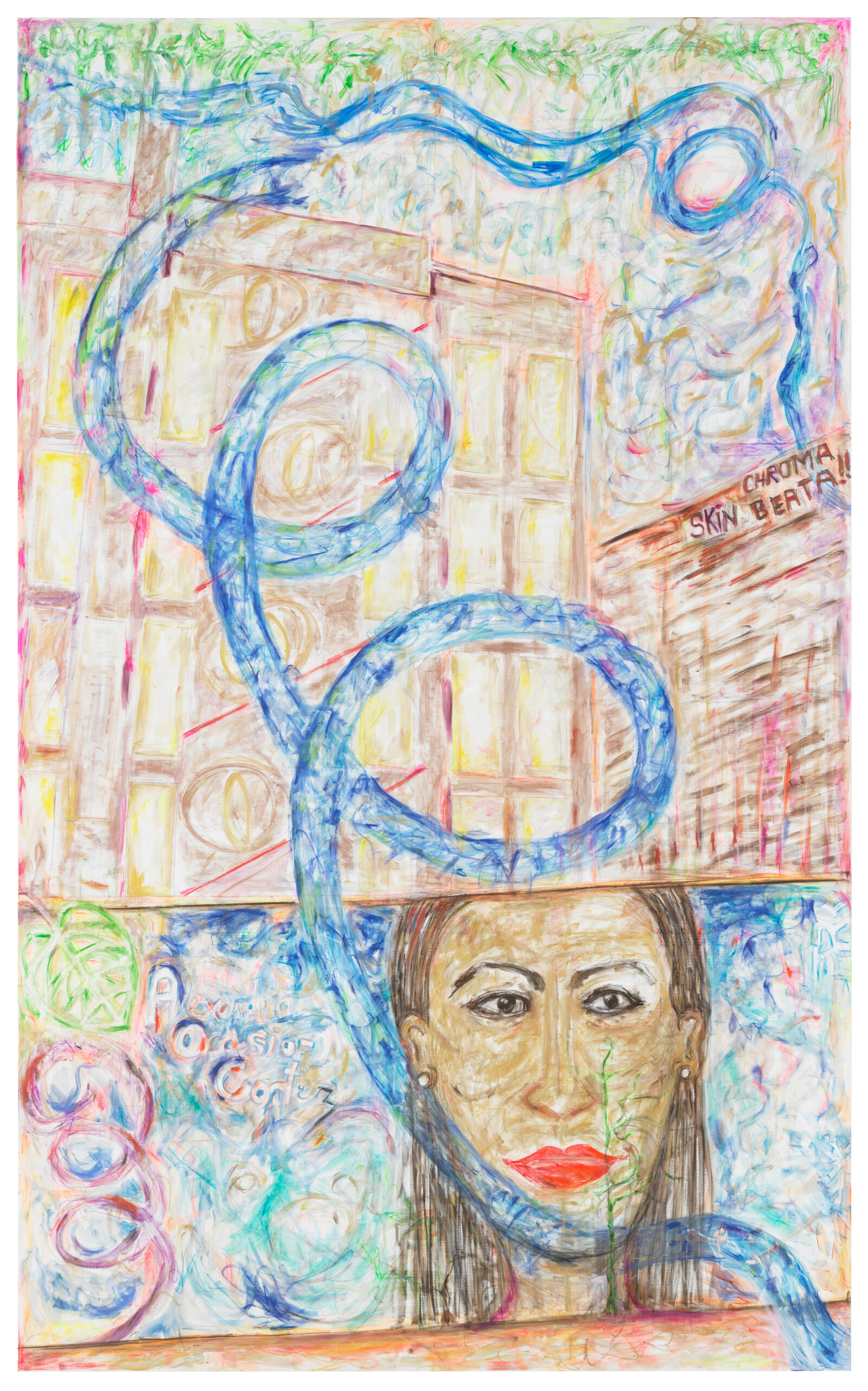

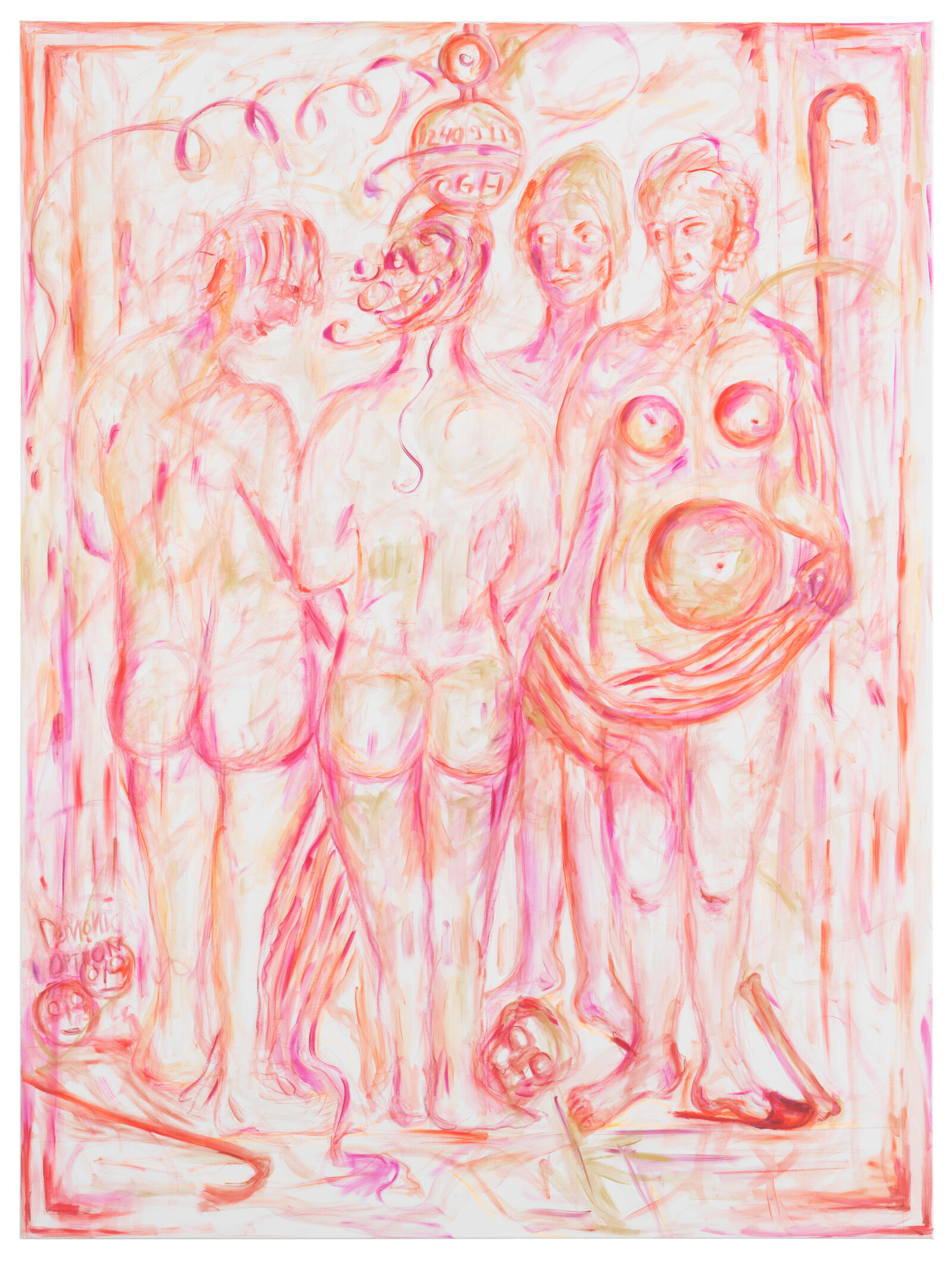

The ground floor debuted a suite of triumphant new works—three large figurative canvases, and two smaller abstract pieces titled Vorhang [Curtains] in her signature palette of reds and pinks. At first glance the portraits Neue Frau [New Woman], Neuer Mann [New Man], and Encore, all from 2019 with a color scheme of contrasting pastels, appear optimistic about the state of feminism. Neue Frau, an exaggerated vertical canvas measuring just over 133 by 82 inches, depicts the progressive New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez across a mottled urban backdrop. Neuer Mann—a companion painting with the same dimensions—shows two male figures imposed against a plane of faint, breast-like forms; one holds a plant, while the other plunges headfirst into a void. Encore, an imposing horizontal canvas, features an avatar of Koether gazing out from a proscenium stage to a crowd rendered in post-Impressionist blurs. The subjects of all three canvases are accompanied by ribbons—a type of strategically deployed feminine motif, like tears and hearts, that she calls “fem-trash.”1 Koether’s likeness grasps two ends of a bow in outstretched arms, each hand wielding paintbrushes, in a clear gesture of pride. By contrast, a strip of ribbon swirling above Ocasio-Cortez’s head ominously crosses her neck. In Neuer Mann, a swath of fabric spools around the falling body. Rather than connote liberation, Koether’s ribbons are ambiguous objects that call attention both to women’s high-profile success in public life and the vengefulness that it inspires in response. In the portrait of Ocasio-Cortez, for example, they remind the viewer that this is an outspoken intersectional feminist whose anti-capitalist politics have made her both an icon of the left and the target of regular death threats from the right.

Koether’s new work fits with the global vogue for eccentric figuration, but this exhibition evinces her decades-long critical investigation of painting’s patriarchal bias. She began painting in Cologne in the 1980s, at a time where neo-Expressionist bravado and the bombastic post-Conceptualist antics of Martin Kippenberger vied for supremacy. By contrast, her early canvases, including nudes and a 1983 abstraction titled Max Ernst, embrace various Surrealist traditions. Edie, a small impasto of a headless, seated nude woman also from 1983, reveals her exposed vulva echoed in two floating ovoid forms: its expressive intensity marks it as an outlier among other works from the period. On the exhibition’s top floor, another set of paintings from 2019 revisit the complications of multi-figure compositions by artists including Albrecht Dürer and Lucian Freud. The lingering influence of Edie, however, could best be seen in Pink Ladies 2 and 3: fields of quasi-abstract, organic forms inspired by a quote by Katherine Mansfield, in which the modernist writer likens her body parts to apples. Koether is far from an essentialist. These works, however, show her willingness to engage with feminist subject matter to complicate—even contaminate—the history of painting.

Entering German painter Jana Euler’s solo exhibition “Unform” at Artists Space, my anxiety spiked. I was greeted by two workers vigorously disinfecting the surfaces around Euler’s 2020 series “Slugs”—large, soft sculptures, painted in ochre and orange acrylics, that resemble Kafkaesque bugs. Euler had clamped these around the gallery’s cast-iron supports, securing one to the exterior of the building with ratchet straps. The indoor “slugs” assumed various positions: slumped on the floor (Unstretched, leaning, relaxed), stretched onto a circular support suspended around a column (Unstretched, masturbation on column), and confrontationally erect (Unstretched, ramming force). A generation younger than Koether, Euler has inherited the former artist’s interest in staging, particularly effective here in her embrace of the grotesque.

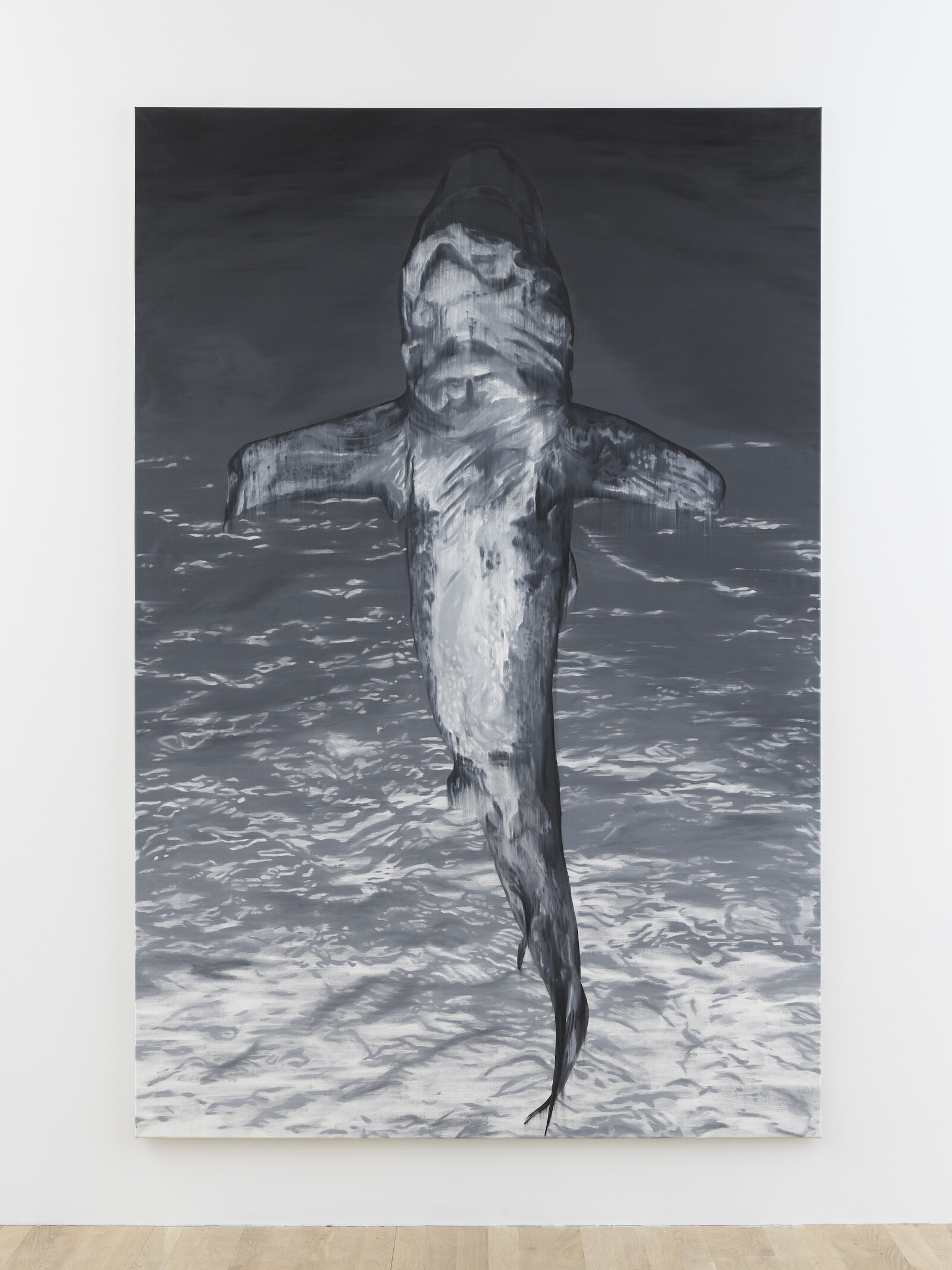

Euler began painting portraits as an art student at Frankfurt’s Städelschule, visualizing the power of the network that surrounds art by depicting influential artists and critics (mostly male) with their astrological signs.2 Her recent canvases exaggerate bodily proportions with compressions and distortions that respond to—if not emulate—the conditions of the screen. Under Distraction illustrates a kaleidoscopic view of cigarettes, pizza, and other vices, seen through a pair of hollow eyes. With more convincing violence, Close Rotation (Right) and Close Rotation (Left) (both 2019) depict two men in briefs, hemmed in tightly by a frame. Like Koether, Euler attacks the legacy of painting by men with equal parts cold-blooded precision and gusto. Recently, she has arrived at a series of shark paintings that mimic the style of various male painters. While the sharks’ bodies are plainly phallic, the fearsome animals’ bared teeth also nod to the ancient myth of vagina dentata—an interpretation often mapped onto analyses of Jaws (1975).

Kirsty Bell writes of these “Great White Sharks” as an allegory for decaying male power: “They seem to present the last gasps of a species living off its own notoriety, but undercut by a creeping sense of fear and vulnerability.”3 At Artists Space, Euler showed gwf 9, Richter/Baselitz (2019). The composition is an analogue for the limits of male power in the face of a crisis—be it a sex scandal or a pandemic. Like Georg Baselitz’s inverted paintings, to which the title alludes, Euler painted the composition upside-down, first rendering the animal diving toward the ocean—much like the inverted central figure in Koether’s downward-spiraling Neuer Mann. Flipped upward, the cruciform pose appears awkward and flailing, an effect enhanced by the palette of tonal grays borrowed from Gerhard Richter. Euler’s and Koether’s work points toward a decline in patriarchal power, but suggests that it won’t go down without a fight.

Online viewing rooms

Jutta Koether’s “4 the team” / Jana Euler’s “Unform”

An excerpt about feminine excess from Koether’s “Fem-Trash-Manifest,” published in Eau de Cologne 3 in 1989, resonates with the current exhibition: “Die eigene Unnatürlichkeit als Frau im Kapitalismus steigern. Offensiv gebrochen sein, ‘krank’ sein, Vielfachfunktionen einnehmen, sich zelebrieren.” (Increase your own unnaturalness as a woman in capitalism. Celebrate being aggressively broken, being ‘sick,’ performing multiple functions.) Translation by the author.

Art historian David Joselit’s 2009 article “Painting Beside Itself”—in which he discusses “Lux Interior,” Koether’s exhibition from that year at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, at length—analyzed how painting “belongs to a network.” See Joselit, “Painting Beside Itself,” October 130, Fall 2009, 125–134.

Kirsty Bell, “How Jana Euler’s Phallic Sharks Are Waging War on Art-World Disparity,” Frieze, June 27, 2019. https://frieze.com/article/how-jana-eulers-phallic-sharks-are-waging-war-art-world-disparity.