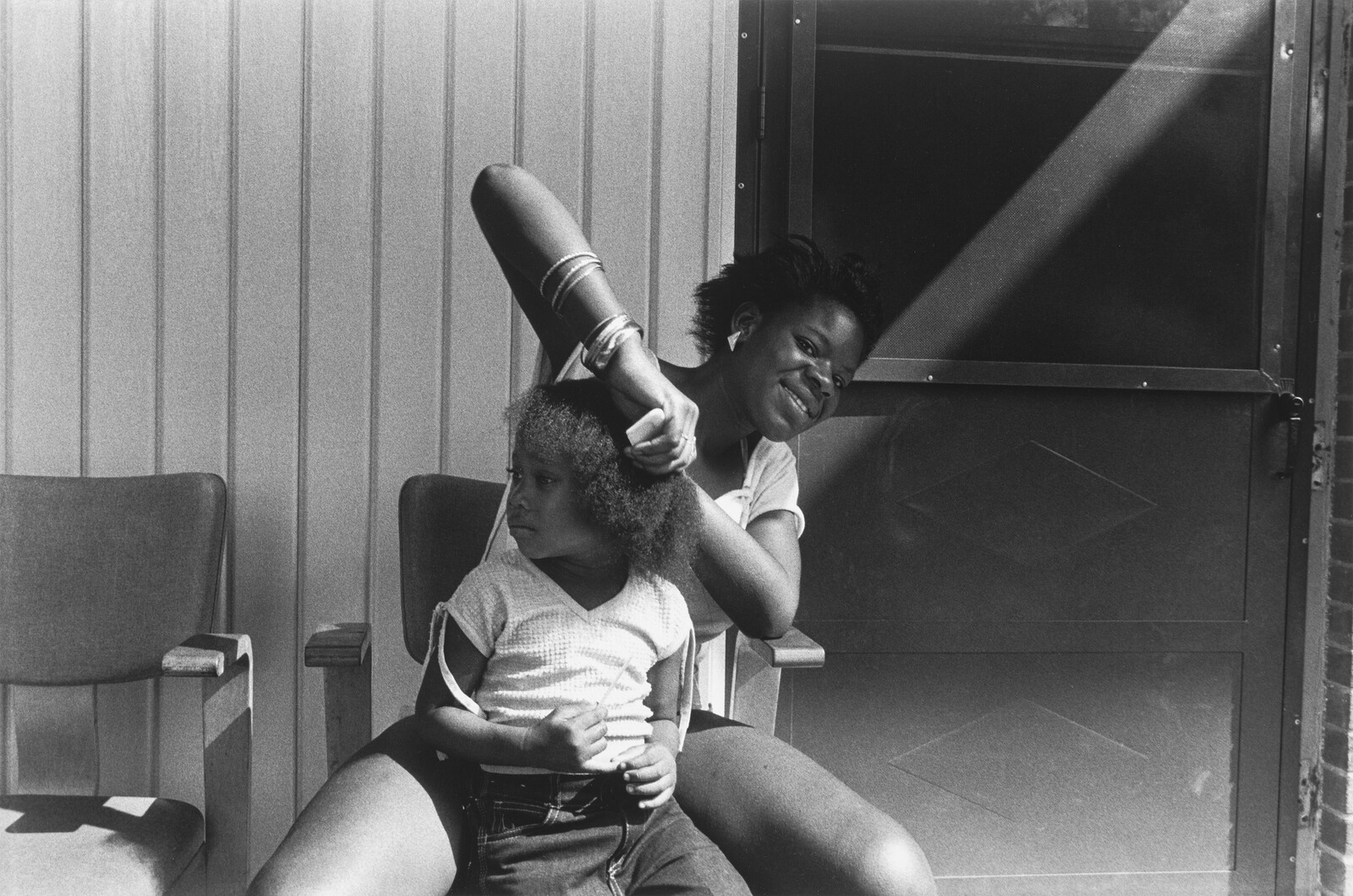

Earlier this month, the touring exhibition “Dawoud Bey: An American Project” arrived at the High Museum in Atlanta, Georgia. This retrospective of the photographer’s 45-year career—which opened in February at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and will move next spring to New York’s Whitney—features portraits and photographs from the 1970s to the mid-2000s. These black-and-white images are often shot outdoors and depict majority Black communities in the US—such as those in Brooklyn, Harlem, Orlando, and Birmingham—engaging in everyday activities and moments of communal joy. “An American Project” also features works from Bey’s 2017 series “Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” which comprises large, dark rural landscape photographs taken at sites rumored to have been stops on the Underground Railroad, along which Black people travelled in secret to escape slavery. By presenting these two seemingly disparate projects simultaneously, this retrospective insists that viewers attend to both types of works together; in doing so, the exhibition aims to overcome a common thematic split between images that depict people and those, like landscapes, that do not. Considering these works as continuous, however, reveals fruitful new ways of thinking.

The gelatin silver prints in “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” are moody and dim, overlaid with a sheen that is almost gritty in texture thanks to the coated paper they are printed on. The trees, fences, lakes, and buildings in the photos are initially obscured, purposefully made more difficult to see through Bey’s printing methods (which take advantage of the light sensitivity of silver particles as well as their ability to be chemically “toned” through the introduction of other substances). These images resist both reproduction and easy interpretation. That one also has to wait for one’s eyes to adjust to the darkness, before slowly traveling over the terrain of each picture, reminds the viewer that the formerly enslaved people who traversed these sites often did so under cover of darkness. Darkness here is multivalent: its obscuring power, which prevents viewers from immediately processing the whole of Bey’s photographs, aided formerly enslaved people in their escape. The Underground Railroad, as the artist has noted, occupies a semi-mythological place in American history, and some of the places Bey photographs are only cannot be confirmed to have been stops on the Railroad. Like the experience of slavery, these places are unrepresentable. They are half-shrouded locales that evade being captured on a map or in a photo.

Though these photographs are dark, they are shot in the daylight and processed in such a way as to make them initially appear to be taken at night. They bring to mind Hiroshi Sugimoto’s eerily beautiful “Seascapes” series (1980–ongoing), which are shot at night, the film exposed for different lengths of time in order to reveal how light plays even after dark. Yet there is no analogous method for bringing night to the day. Bey may make his photos dark, but this is achieved through processing and glazing the finish image, which occurs after the initial act of taking the photograph. How can we account for Bey’s artificial night?

The philosopher François Laruelle’s 2011 book The Concept of Non-Photography suggests one answer to this question. In essence, Laruelle starts with the premise that works of art cannot and do not represent anything, be it objects, thoughts, concepts, or movements. He posits art as an entirely self-sufficient engagement with the world (which he calls the Real), independent even of viewer and creator. Art is a machine; the medium, processes, and even the artist are its materials. What art “shows,” Laurelle argues, is only the world according to itself—which he terms the world-in-painting, the world-in-photo, and so on. He turns to photography in part because of its connection to modern scientific advancement and its attempts literally to illuminate the world “objectively.” Non-photography aims to re-conceptualize the photographic flash, which Laruelle associates with the flash of logos or reason, as a form of potential insurrection against its traditional association with illumination, and against photography’s constant reproduction of the asymmetrical dichotomy between light and dark.

Early film was designed with light skin as the model. Kodachrome—an early color film made by Kodak—used what were called “Shirley cards,” named after the white woman whose picture they featured, as the standard color reference when developing images. Unsurprisingly, early film proved inadequate for capturing darker skin tones, sometimes making the person in the picture almost entirely invisible. Kodak only adjusted their film when companies complained that it was poor at photographing products such as chocolate and wood. Today, facial recognition technology regularly fails to capture Black people and people of color as well as it does white people. Ironically, these groups are much more often targets for surveillance.

In non-photography, the photo is a clone, a fabulation. For Laurelle, “[t]he photo is the first presentation of identity, a presentation that has never been affected and divided by a representation.” Moreover, each photo is itself a complete clone of the world. Read in this way, Bey’s photographs do not create a new type of night. Instead they are photographs of the night—meaning a combination of Bey’s photographic and printing processes. These images do not represent anything; they are not pictures of anything. Rather than being images of the Underground Railroad that give insight into their subject matter through the “objective” medium of photography, they are clones of the Underground Railroad—in-photo, as Laurelle would say—whose reality is the mythological and the photographic, whose only night is the one created by Bey. The series title is taken from a line of Langston Hughes’s 1926 poem “Dream Variations.” Alongside their association with darkness and night, Bey’s photographs explore another valence of dreams: their status as utopian fiction without fixed location or rigid definition. Dreams are spaces that do not yet exist, except by escape through an unknown night.

What new ways of looking at “An American Project” take shape if we re-examine the status of a retrospective as a simple collection of an artist’s works over time? The vertical and horizontal lines cutting slices from A Boy Eating a Foxy Pop, Brooklyn, NY (1988) and the barely visible horizon of Untitled #9 (The Field) (2017) are part of the same unwritten history. Rendering void the artificial separation of Bey’s works between portraiture and landscape allows them to unite under the banner of the uninterpretable night-in-photo. It also re-affirms Bey’s status not only as artistic producer but as curator of these installations—not traditional museum curation so much as a process of care-taking that creates one’s own experience of the world.

When the “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” series was first exhibited, at The Art Institute of Chicago, in 2019, a collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographs, which Bey selected from the museum’s permanent collection, hung at the exhibition entrance in a formation resembling a cloud. In contrast to Bey’s own photographs, these works featured multiple portraits of African-Americans throughout history, including images from the Civil Rights era, like Gordon Parks’s The Invisible Man, Harlem, New York (1952), as well as an iconic daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass by Samuel J. Miller, which captures Douglass’s fervor and gravity of presence in great detail. Douglass, who had himself escaped slavery and then fought for abolition, was keenly aware that this image would be widely distributed and seen by his supporters. Parks’s piece, a gelatin silver print (like Bey’s) showing a young Black man climbing out of a sewer grate in Harlem, was created as part of a series that explicitly set out to illustrate Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man. Published the same year as Parks’s photo, the novel depicts an unnamed Black protagonist who journeys from the American South to Harlem, and from his subterranean home to the world above. Bey’s photographs could be seen as separate from the pieces chosen from the museum’s collection, with the latter serving as a kind of introduction, divided from the exhibition proper by virtue of their placement just outside the gallery doors. By utilizing other people’s images of Black figures, important sites, and even versions of the Underground Railroad journey, Bey instead positioned his own work as continuous with the curated selection.

Non-photography claims that both sets of photographs, despite their differences in era, subject matter, style, and even creator, are all equally “clones.” Read in this light, these works—the curated selection and Bey’s originals—formed a cross-temporal collaboration which, while arranged by the artist, more closely relate to Langston Hughes’s original poem than to any periodized or historical delineation of Bey’s work. Non-photography does not seek to articulate a programmatic vision of a new mode of photography; nor does it turn the night into something good, something with its own brightness. Instead, it offers a disruption of hegemonic interpretations that leaves a negative space to be filled by the night itself, a fiction of its own making.

“Dawoud Bey: An American Project” is on view at the High Museum, Atlanta through March 14, 2021. The exhibition is co-organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.