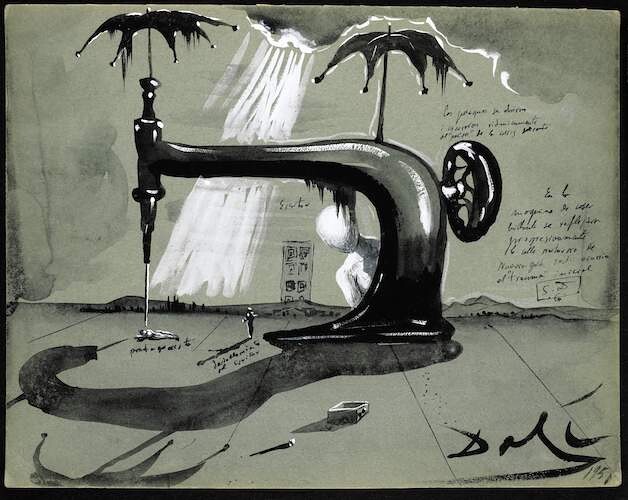

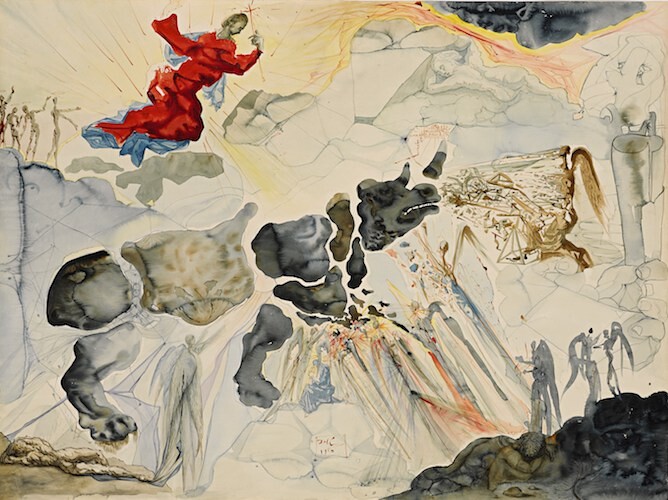

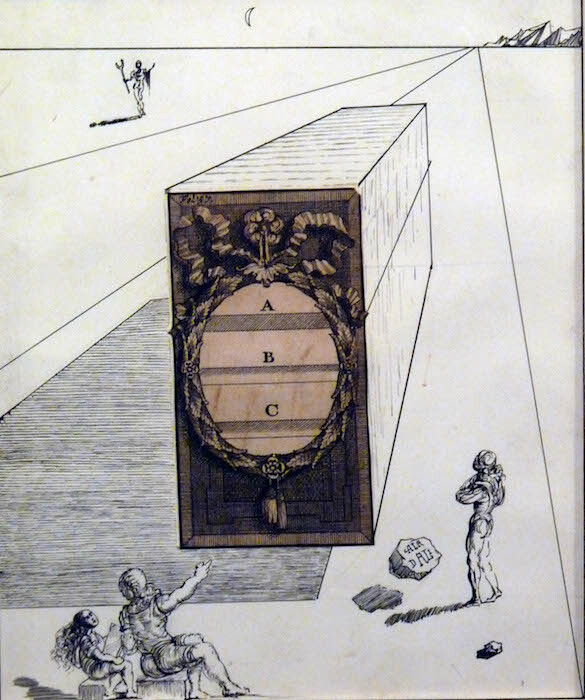

Earlier this summer, after a public talk between Elena Sorokina and my wife, Chus Martínez, the three of us were invited by Eduard Mayoral of Galeria Mayoral to dinner. We hadn’t yet reached dessert when Eduard asked us what to make of Salvador Dalí. They were about to open a group exhibition, “The Space of Dreams,” curated by poet Vicenç Altaió, that would include Dalí’s work. Last year the gallery had also exhibited a series of six of Dalí’s fashion sketches from 1965, with elegantly absurd designs for beachwear and evening robes. These drawings were still for sale for 100,000 euro each.

Apart from his major paintings, the market for Dalí remains murky. Not only did he flood the market by signing all and everything, his historical importance is also in question. When I interviewed Boris Groys in 2010,1 he used Dalí as a perfect example of an artist who didn’t manage to appeal to both “the mass public and the informed part of the audience.” “Dalí overdid it, lapsed too far into poor taste and did not stand in any central tradition.”

The typical counter-example of someone catering to the art elite and the masses equally (who Groys also mentioned) is Andy Warhol. He loved to sell a lot, but unlike Dalí he wouldn’t produce work without an attendant demand. Warhol continued to be accepted as a major figure in Pop Art while the Surrealists made fun of Dalí with the anagram avida dollars and conducted a “trial” in 1934 to kick him out of Surrealism. Both did TV commercials: Dalí for Alka-Seltzer, Corona beer, Lanvin chocolate, Veterano brandy, and Braniff Airways; and Warhol for Diet Coke, TDK video tapes, Chemical Bank, the restaurant chain Schrafft’s, and Braniff Airways. Warhol was even more eager to mingle with the rich and famous but he also surrounded himself with a cohort of hip bohemians. Dalí instead withdrew to his provincial hometown of Figueres in fascist Spain and engaged peasants to participate in his performances. Warhol’s trademark, the silver wig, symbolized technical artificiality; Dalí’s trademark, the curved mustache, had an aristocratic allure. Warhol made the most of his shyness and played cool; Dalí’s words, gestures, and artworks were all ridiculous exaggeration. No matter that Dalí’s career started decades earlier and that Warhol named him a main influence—Dalí ended up as his own caricature.

However, when our conversation turned to Warhol versus Dalí, Chus and I had no doubt about whom to regard as more important:

– Dalí, of course! Warhol was a dead end. A zillion art students and garage bands copied his minimal appearance and coquettish cynicism (it was just too easy) but today, is there a single remarkable artist whose work and persona improves upon Warhol?

Our hosts kept quiet.

– Now think of Dalí. Our dear friend Albert Serra, one of today’s greatest filmmakers, appears as Dalí’s reincarnation along the lines of Rich Dad Poor Dad. Like Dalí, Albert conforms to eccentric forms of masculinity of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. There is a polymorphous ambiguity that got lost in the twentieth century and that now has to be slowly restored. Dalí still had it—he is the missing link on the most popular level. Despite all his public silence we know that Warhol led an ordinary gay sex life. But Dalí? We still have no idea if he ever had intercourse and have to dig out his remains to eventually find out.2

– Albert himself is from the Catalan countryside, so it’s easy for him to identify with Dalí. Even more so as Dalí is passé. A typical camp strategy.

– Exactly! Another reason why Dalí is so relevant today. Sure, Warhol and his entourage were into drag. But Warhol’s basic ideas of beauty were totally mainstream: the “superstars” at his Factory and in his films were young, slim, tall white Americans, all too often from rich families. People who didn’t fit into this scheme, like the corpulent Brigid Berlin, were used for contrast as a freak. Same with Warhol’s paintings—their primary colors and flat round shapes follow the taste of their time: a modernized, streamlined art deco. His drug-loaded and cursed “superstars” are pure nostalgia about the Hollywood Babylon of the 1920s. With a background in fashion illustration, Andy Warhol’s art sparked provocation only when he also made things like cans, piss, death, dictators, and electric chairs look beautiful. Warhol was a penny pincher and his Factory a medieval sweatshop on speed. Whereas Dalí went for the privileges of an absolutist king, legitimized merely by the will and the imagination to make use of those privileges in ever new and more breathtaking ways. Think of the international scandal when his muse, partner, and business director, Gala, dressed up for a ball in New York with a baby doll on her head, gripped by a fluorescent lobster and devoured by ants.

– Sounds lame today.

– Really? There’s less and less that you can touch in art.

– Because we are post-shock. We got bored by the shock as such.

– Dalí was not keen on shocks, he just allowed them to happen. When he was painting badly he did it out of impatience. Groys locates the roots of Dalí’s eccentric lifestyle in Gabriele d’Annunzio. But d’Annunzio still fought a war to establish his micro-state Fiume and his estate at Lake Como was sponsored by Mussolini. It’s like Faust, who needs the devil to make his dreams come true. Gala and Dalí’s creative kingdom is cargo cult come true: all you need is an outlandish artistic talent to seduce the masses, then cash in, build your own dream castle and reign over your fans. Let a brush, a piano, or a mic be your scepter. The art world wasn’t fond of Dalí’s formula as it undermined the checks and balances of collectors, critics, and curators. But in pop music, it gained an enormous appeal beyond social boundaries, from Elvis Presley to Michael Jackson, Prince, R. Kelly, the Kardashians, Kanye West…

– While Albert still sort of lives with his parents.

– That’s the next step. You can do even without the market. You don’t have to build castles with real bricks and real gardeners, you can simulate it in Minecraft. Or you can make things partly true, like in augmented reality. Cosmetic surgery is getting cheaper and cheaper, and then there’s genetic engineering. Or, like Dalí, you go to a countryside that is still relatively cheap. Like the outsider artists who created their own concrete sculpture parks all over the world.

– That’s exactly where Groys puts Dalí: outside of central traditions. People out of touch, insisting on the greatness of their work.

– Would you say the same about hip-hop? “I’m a genius,” “I’m number one”—like Dalí, rappers are excessively reasserting to themselves and the world that they are the greatest. That’s what hip-hop is all about: to perform this claim in such a skillful way that it is heard and approved. The Hippocratic Oath for contemporary artists says that there are no geniuses and that everything you create is derivative. You are just another position in a stream of positions. But what is this good for? To stay humble and realistic to then on top get squeezed by the market? Have you observed the dignity with which tourists move their selfie-sticks? Again, they work as a scepter, reliably putting you at the center, wherever you are. Dalí explored this dignity—the self-creation from your own egg—like no one else…

I don’t recall how our conversation ended. Did we even have dessert? We definitely didn’t help selling Dalí.

Boris Groys in Conversation with Ingo Niermann, “The Future of Art: Boris Groys, Part 17/21,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYdFgTeHZEI.

Raphael Minder, “Salvador Dalí Was Not Woman’s Father, DNA Test Shows,” New York Times, September 6, 2017: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/06/arts/salvador-dali-paternity-lawsuit.html?_r=0.