September 18, 2019–January 5, 2020

The postindustrial exhibition site is a cliché of contemporary biennales, but Lyon’s Fagor factory has an engaging history. Founded in 1956, Spanish appliance manufacturer Fagor was for decades the largest industrial worker-owned cooperative in the world. When the company acquired Brandt, the new French subsidiary Fagor Brandt commanded a significant chunk of the European domestic goods market. In the 1980s, almost 2000 people worked at the Lyon factory producing washing machines; by the 2000s, only 400 were employed there. After the 2008 crash, when many people could no longer afford to buy houses, they stopped purchasing home appliances too. An attempted conversion to producing electric cars failed, and the factory closed in 2015. Floor markings that once directed the choreography of the production line remain, as do a handful of windowed structures, from which processes or workers were observed, alongside redundant machinery, and graffiti from the building’s vacant years. Abandoned on site, an absurd 2007 limited-edition top-loading washing machine upholstered in pink satin, by lingerie designer Chantal Thomass, bears witness to Fagor Brandt’s death throes.

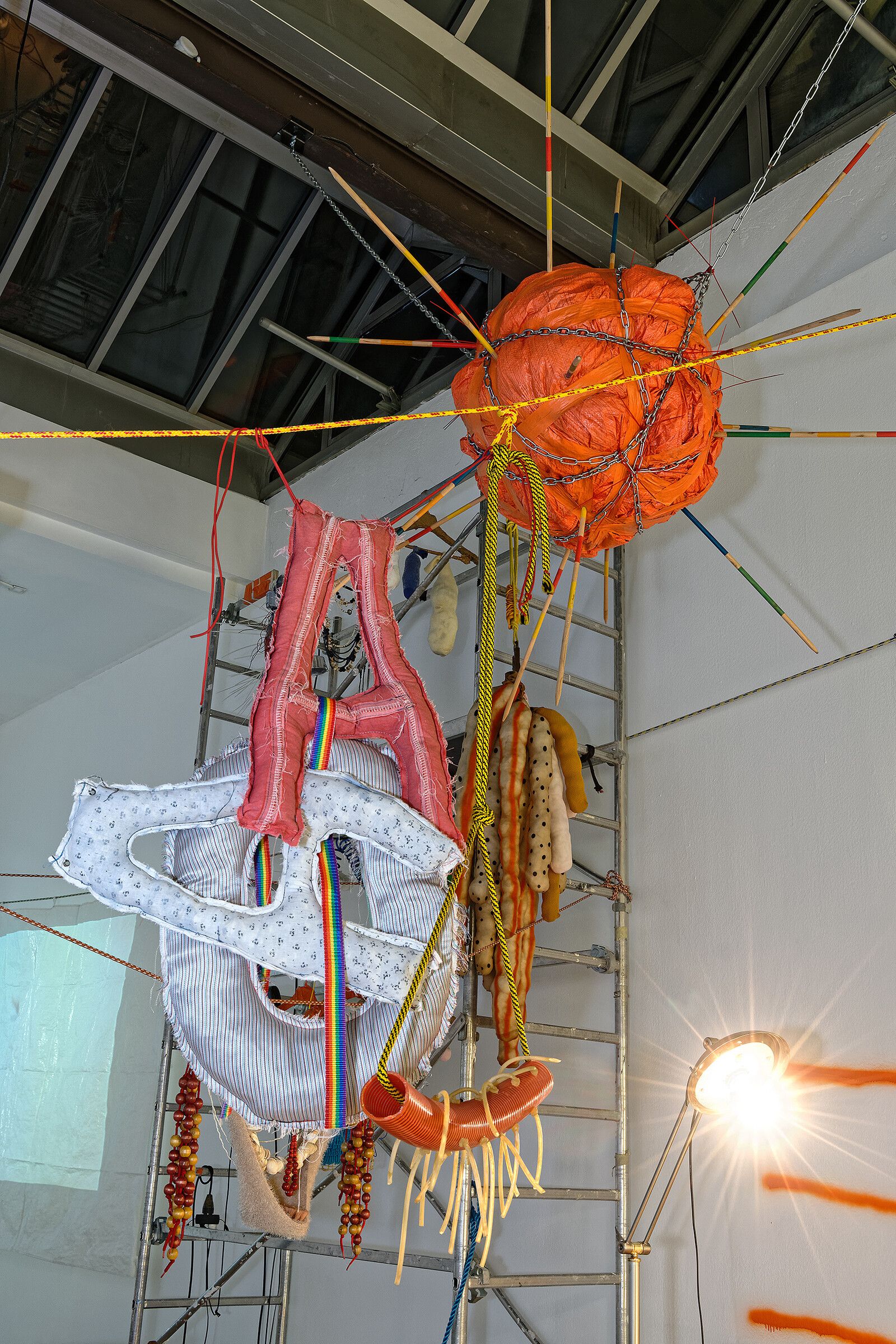

While the main venue is monolithic, an immovable monument to a former industrial era, the exhibition emphasizes flows with a title borrowed from a Raymond Carver poem. It’s apt for the city where the Rhône and Saône rivers meet and, more pressingly, for an exhibition populated by artists who envisage fluid meetings, intermingling, and hybridity. Works by 47 artists, most of them newly commissioned by the team of 7 curators from Paris’s Palais de Tokyo, sprawl over 4 echoing halls at the Fagor factory. The pieces fight to retain the viewers’ attention amid a near-total absence of exhibition architecture, resulting in a tangle of different textures. When dancers interact with the long gray lycra hangings attached to high ceiling lights in Malin Bülow’s installation Elastic Bonding (all works 2019 unless otherwise stated), they writhe unnervingly, as if rendered bestial through their communion with the building. Simphiwe Ndzube offers two contrasting caravans in transit through the exhibition: in In the Land of the Blind the One Eyed Man is King?, a clutch of downtrodden, wasted, and bulging figures lug burdens, their faces turned from viewers, while in Journey to Asazi, crossed sticks, booted and gloved, stride toward a rowing boat in which two figures bearing parasols are borne serenely away.

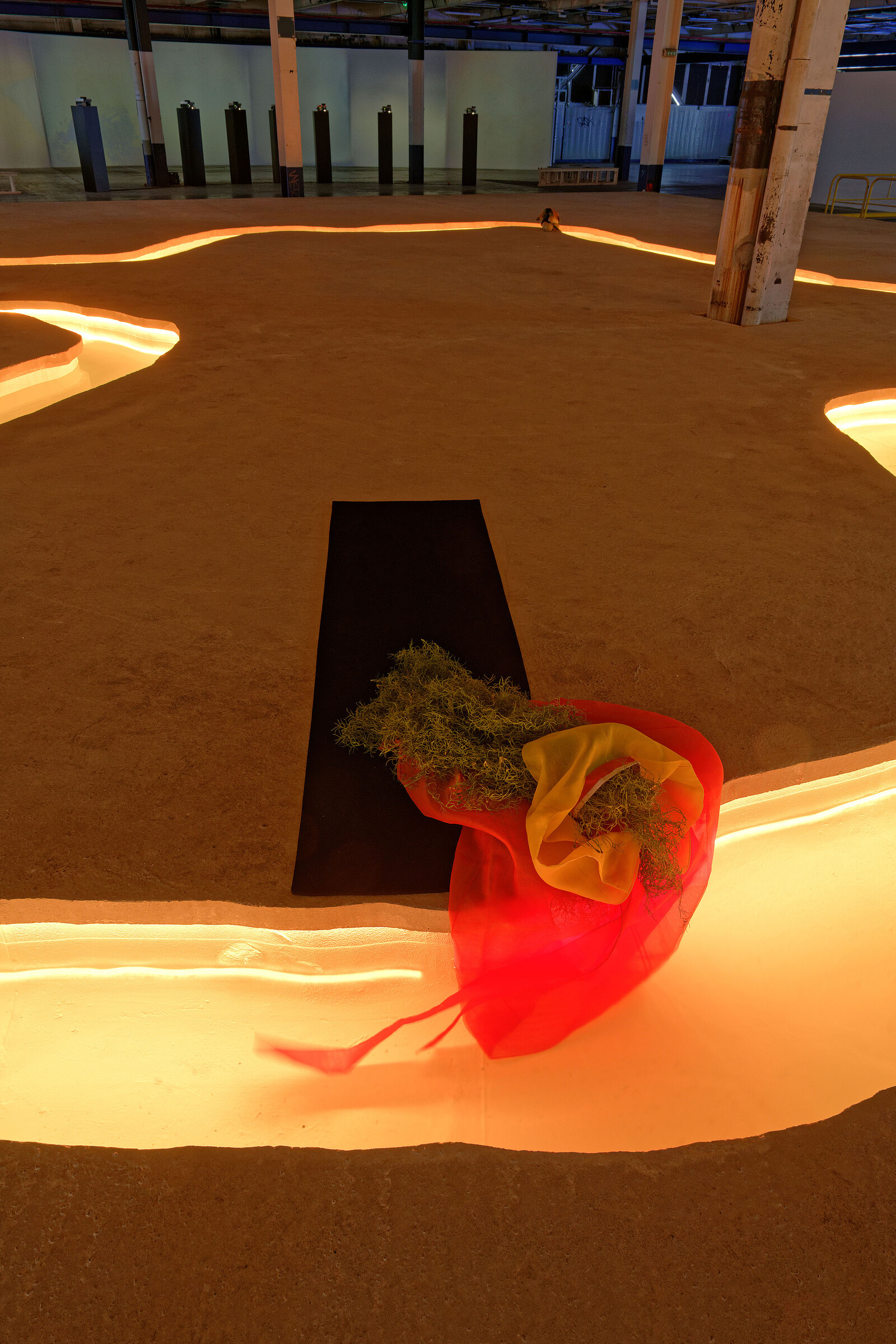

Minouk Lim’s Si tu me vois, je ne te vois pas [If you see me, I don’t see you] is positioned near the entrance of a low-lit hall. Chiming with the biennale title, the installation’s stream of hot, revolving water, set into a raised floor and illuminated yellow, is as natural as a spin cycle; kitsch though it is, a bobbing, oversized pinball and a trailing red garment based on a traditional Korean shroud together illustrate a heritage at the mercy of the vagaries of skittish times. Here too is Gustav Metzger’s Supportive (1966–2011), a trio of liquid crystal projections that continually morph in response to the projectors’ heat, light, and movement.

Evolution is embedded in the latest iteration of Thomas Feuerstein’s Prometheus Delivered (2017–19), an extensive laboratory in which the artist employs bacteria to dissolve a marble Prometheus and attempts to grow the eagle-pecked hero an ersatz liver from human cells which, when fermented and distilled, produce alcohol. There’s even the repulsive prospect of extending the cycle by drinking the spirit produced—it’s bottled and labeled Aithon, after the bird that tormented the Titan—to the detriment of one’s own organs. Feuerstein’s tangled machinery is nonetheless straightforward in comparison with Sam Keogh’s Knotworm. Alongside the mechanical might of the front of a tunnel-boring machine placed on the floor of the hall is a scrappy grove of trees fashioned from sticks planted in toilet bowls and hung with garlands of toilet paper and taped-on photocopies. A video playing on a monitor in the lap of the machine tells a tale that tunnels and spirals through the subsoil of West London, touching on Doris Lessing’s 1985 novel The Good Terrorist, owners of empty properties cementing toilets to discourage squatting, artists’ studios (a precursor to gentrification), Battersea Power Station, buddleia flowers, and rhizomatic knotweed burrowing under buildings. The solid stuff under our feet, the work suggests, is also in continual motion and rooted in a broader, messy, political context. Yet Keogh’s concentrated engagement with his locality casts a questionable light on the Fagor factory site and the curators’ strategy in using it: the biennial is cementing the location in a new leisure economy. Erstwhile graffiti artist Stephen Powers’s Open Door, a sanctioned, spray-painted message on the building exterior reading “WARM IN YOUR MEMORY,” gains traction from nostalgia—and will look good in the brochures.

The other principal venue, the Musée d’Art Contemporain de Lyon, provides generous platforms for eight artists. There’s a delightful plunge into Renée Levi’s painted rooms, a sea of broad, rhythmic blue strokes over the walls and ceiling, or overwhelming, aggressive pinks: an exceptional (and, rare, primarily aesthetic) experience within the biennale. Daniel Dewar and Grégory Gicquel’s “Mammalian Fantasies” series (2017–19) comprises carved oak cabinets, seating, troughs, and wall reliefs in which humans, pigs, moths, oxen, inanimate objects, and other creatures come together, the pieces placed in stiff, vaguely ceremonial arrangements or hung like church-wall memorials. The reconfigured mammalian hierarchies, which occupy two full floors, scarcely merit so much repetition. Gaëlle Choisne’s Temple of Love – Absence is more provisory, albeit delicately arranged, combining remnants, such as the exotic cigarette butts that dot the walls or the flotillas of fortune cookies on the floor, with larger elements, including fountains that pour water over digital images of plants. With a workshop feel, this space hums with possibilities, suggesting an environment in transition, being redefined, entrenched in inherited systems of consumption or governance yet carving out new room for maneuver.

In addition to a few low-impact interventions in Lyon’s historic center and the Veduta program, which will position artists’ projects in less accessible or tourist-friendly locations, such as Felipe Arturo’s extension of his installation in the Fagor factory onto wasteland in the Velette district, the works of 10 nominally “young” artists are on show at the Institut d’Art Contemporain. Formal components seen elsewhere in the exhibition reoccur: water flows, animate and inanimate come together, as do the human and the machine. Judging by this survey of attitudes, hybridity is simply a given among this peer group. In Randolpho Lamonier’s mixed-media installation Brazil, 2019 – A Dance Score for Fire and Heavy Metals, Molotov cocktails are lined up next to deckchairs: “Against [the] death agenda of the present […] We dance on the debris of this life,” says a video.

What responsibility do we have toward the debris of our forebears? The biennale’s post-industrial setting elicits frisson as a framing device; it is less clear whether it has been done justice. Carver’s title surfaces in the midst of his poem: “The places where water comes together / with other water. Those places stand out / in my mind like holy places.”1 Waters may be fluid and intermingle, but, in Lyon, there is a place in play as well: a fixed point of observation. The curators, however, seem focused on the imperative to keep in motion. Their biennale reflects our times—economically, socially, and politically—but has sent down few roots.

Raymond Carver, Where Water Comes Together with Other Water (New York: Random House, 1985), 17.